By Jim O’Neal

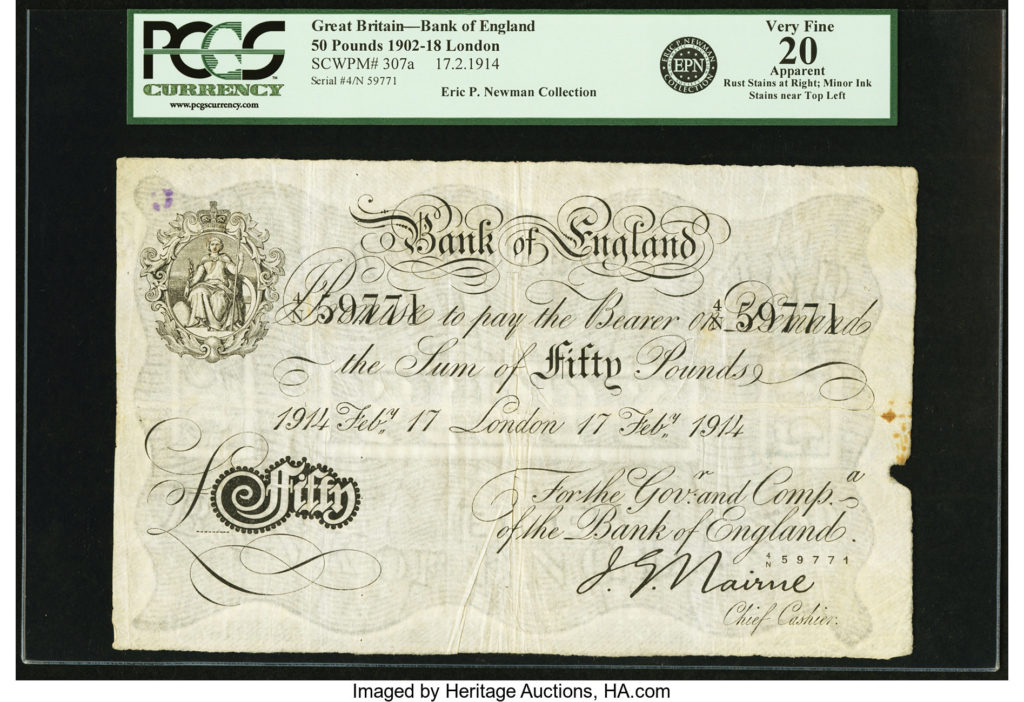

In 2003, I got a reliable tip about a new non-fiction book, The Devil in the White City by Erik Larson. The author skillfully weaves two complex stories into an entertaining narrative. The story revolves around the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (“The White City”) and the riveting true story of H.H. Holmes (“The Devil”). Holmes is credited with being the first American serial killer after he lured as many as 200 people into his “Murder Castle.” At the same time, Jack the Ripper was plying his trade in London. Several attempts have been unsuccessful in linking these two monsters.

In 2010, Leonardo DiCaprio bought the film rights to the best-selling book and, presumably, his production company, Appian Way Productions, will eventually be turning out a movie. A short list of films by the studio includes The Aviator, Public Enemies, The Wolf of Wall Street and the Oscar-winning The Revenant. The production company has collaborated with Martin Scorsese and Clint Eastwood on several entertaining films, but it’s not clear if any other organizations will be involved. Larson went on to write several other excellent books that I can safely recommend for your enjoyment.

The 1893 Columbian Exposition was designed to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ voyages to the New World. The Italian explorer and navigator made four voyages in 12 years (1492-1504), primarily searching for a shorter trade route from Europe to Asia. He was unsuccessful and, curiously, despite never setting foot on North America, is honored with a national holiday. Hence, America derives its name from a different Italian explorer, mapmaker Amerigo Vespucci, who also claimed to have made several voyages to our ZIP code.

However, Columbus is credited with opening the Western World, which resulted in significant trade and the European colonization of our neighbors. His trips include contact with Hispaniola (Haiti and the Dominican Republic), Cuba, Central and South America and several of the smaller Caribbean Islands. Latter-day historians have been critical of his treatment of the indigenous people. In addition to slavery, the “Columbian Exchange” was responsible for exposing local inhabitants to new diseases that resulted in widespread death due a lack of immunity (sound familiar?). Trade provided Europe with an amazing array of new foodstuffs, like the 200-plus varieties of potatoes from Chile, along with tobacco and dozens of others too numerous to list.

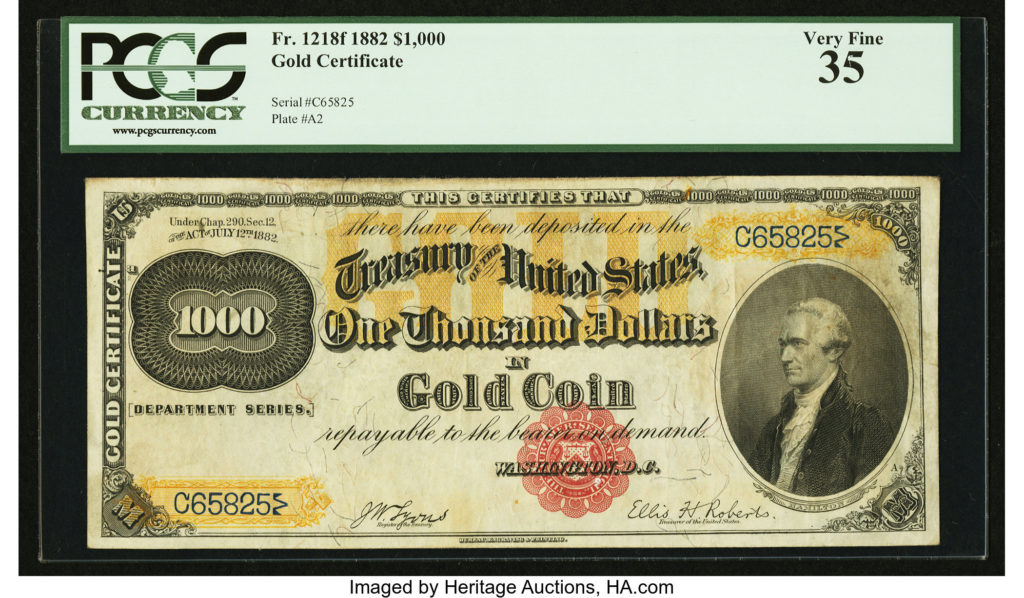

There was vigorous competition to host the 1893 Fair – with St. Louis, Chicago and New York City the leading contenders. NYC had powerful backers, with Cornelius Vanderbilt, William Astor and J.P. Morgan agreeing to provide $15 million in financing. But Chicago had their own heavy-hitters, who matched the $15 million and finally prevailed. They were especially motivated since this kind of visibility would provide an excellent opportunity to demonstrate they had fully recovered from the ashes of the Great Fire of 1871, which was wrongfully blamed on Mrs. O’Leary and her innocent cow. The event was a commercial success, with over 27 million visitors from 46 countries. The “White City” nickname was derived from the color of the facade of the 14 major buildings designed by some of the world’s most prominent architects. Plus, it didn’t hurt that a civil engineer named George Washington Ferris Jr. showed up with his now-famous wheel that could thrill over 2,000 people, fully loaded, at 50 cents per passenger. At over $1,000 per ride, it was the equivalent of having a U.S. Mint without having to buy any silver.

The real factor in the exhibition’s success was the remarkable skill of one man, Frederick Law Olmsted, primarily known for his work as superintendent for Central Park in New York. He had been a mere 35 years old and was soon in charge of thousands of workers. Then, the Civil War started and Olmsted took a short leave of absence since everyone was convinced it would be over very quickly. A carriage accident prevented him from joining the army to fight but, fortunately, he was asked to become the leader of the U.S. Sanitary Commission. When the war started, Northern forces consisted almost exclusively of volunteers that totally lacked the capability to provide medical assistance or even food to wounded soldiers. With Olmsted in charge, the Sanitary Commission raised funding and supplies from ordinary citizens and then devised means to deliver medical attention, food, tents and blankets to wounded soldiers right on the battlefields. This was an early example of Uber, but without an iPhone.

His reputation grew and 30 years later, the CEO of the Columbian Exposition hired him to organize everything in Chicago. Piece of cake.

I hope President Biden can find someone with just 5 percent of Frederick Olmsted’s skill and experience. Otherwise, it’s going to be a long four years.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].