By Jim O’Neal

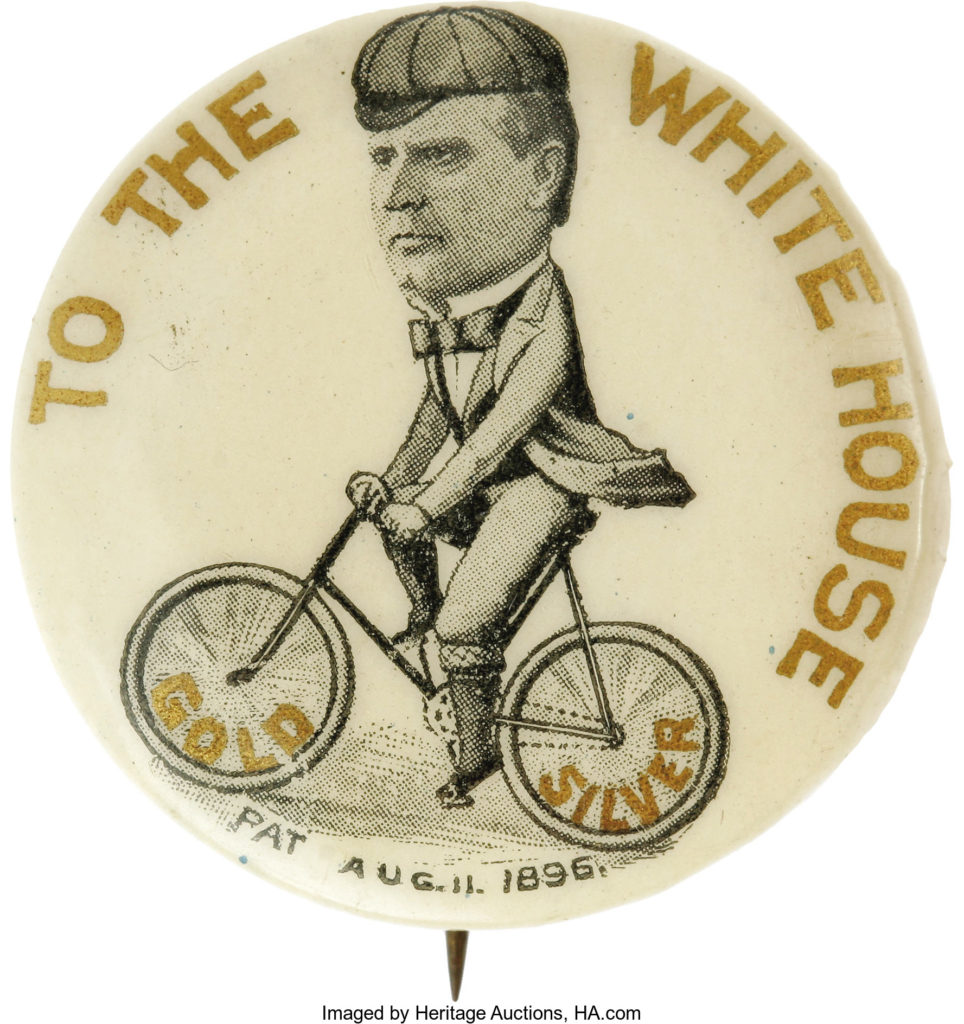

As the bicycle became more popular in the latter part of the 1800s, it was inevitable that millions of new enthusiasts would soon be demanding better roads to accommodate this object of pleasure, so symbolic of progress. It was hailed as a democratizing force for the masses and neatly bridged the gap between the horse and the automobile, which was still a work in progress.

The popularity of this silent, steel steed had exploded with the advent of the “safety bicycle” (1885), which dramatically reduced the hazards of the giant “high wheelers.” The invention of the pneumatic tire in 1889 greatly enhanced the comfort of riding and further expanded the universe of users. However, this explosion in activity also increased the level of animosity as cities tried to cope by restricting hours of use, setting speed limits and passing ordinances that curtailed access to streets.

There were protest demonstrations in all major cities, but it came to a head in 1896 in San Francisco. The city’s old dirt roads were crisscrossed with streetcar tracks, cable slots and abandoned street rail franchises. Designed for a population of 40,000, the nation’s third-wealthiest city was now a metropolis of 350,000 and growing. On July 25, 1896, advocates of good streets and organized cyclists paraded in downtown with 100,000 spectators cheering them on.

The “Bicycle Wars” were soon a relic of the past as attention shifted to a product that was destined to change the United States more than anything in its history: Henry Ford’s Model T. Production by the Ford Motor Company began in August 1908 and the new cars came rolling out of the factory the next month. It was an immediate success since it solved three chronic problems: automobiles were scarce, prohibitively expensive and consistently unreliable.

Voila, the Model T was easy to maintain, highly reliable and priced to fit the budgets of the vast number of Americans with only modest incomes. It didn’t start the Automobile Age, but it did start in the hearts and souls of millions of people eager to join in the excitement that accompanied this new innovation. It accelerated the advent of the automobile directly into American society by at least a decade or more.

By 1918, 50 percent of the cars in the United States were Model Ts.

There were other cars pouring into the market, but Model Ts, arriving by the hundreds of thousands, gave a sharp impetus to the support structure – roads, parking lots, traffic signals, service stations – that made all cars more desirable and inexorably changed our daily lives. Automotive writer John Keats summed it up well in The Insolent Chariots: The automobile changed our dress, our manners, social customs, vacation habits, the shapes of our cities, consumer purchasing patterns and common tasks.

By the 1920s, one in eight American workers was employed in a related automobile industry, be it petroleum refining, rubber making or steel manufacturing. The availability of jobs helped create the beginning of a permanent middle class and, thanks to the Ford Motor Company, most of these laborers made a decent living wage on a modern five-day, 40-hour work week.

Although 8.1 million passenger cars were registered by the 1920s, paved streets were more often the exception than the rule. The dirt roads connecting towns were generally rutted, dusty and often impassable. However, spurred by the rampant popularity of the Model T, road construction quickly became one of the principal activities of government and expenditures zoomed to No. 2 behind education. Highway construction gave birth to other necessities: the first drive-in restaurant in Dallas 1921 (Kirby’s Pig Stand), first “mo-tel” in San Luis Obispo in 1925, and the first public garage in Detroit in 1929.

The surrounding landscape changed with the mushrooming of gas stations from coast to coast, replacing the cumbersome practice of buying gas by the bucket from hardware stores or street vendors. Enclosed curbside pumps became commonplace as did hundreds of brands, including Texaco, Sinclair and Gulf. The intense competition inspired dealers to distinguish with identifiable stations and absurd buildings. Then, in the 1920s, the “City Beautiful” movement resulted in gas stations looking like ancient Greek temples, log cabins or regional Colonial New England and California Spanish mission style fuel stops.

What a glorious time to be an American and be able to drive anywhere you pleased and see anything you wished. This really is a remarkable place to live and to enjoy the bountiful freedoms we sometimes take for granted.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].