By Jim O’Neal

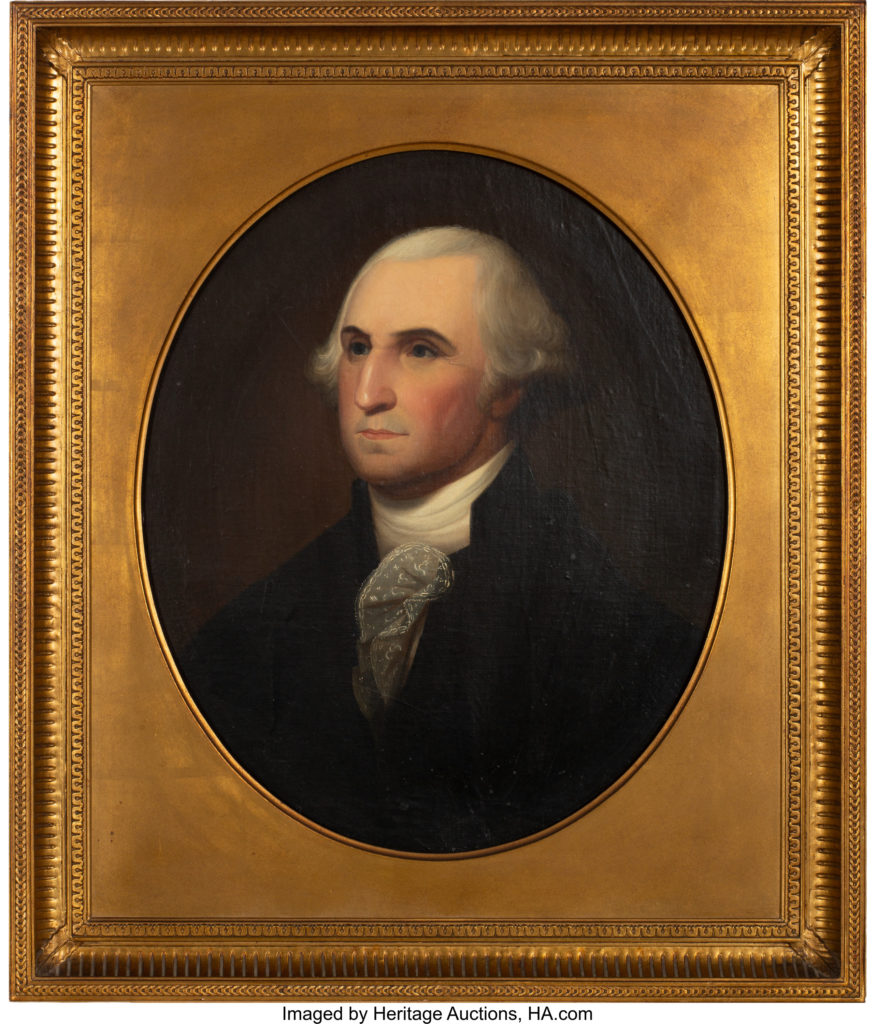

The 19th century in the United States was by any standard an unusually remarkable period. In 1800, John Adams was still president, but had lost his bid for re-election to Vice President Thomas Jefferson, the man behind the words in our precious Bill of Rights. Alexander Hamilton had used his personal New York influence to break a tie with Aaron Burr, since Jefferson was considered the least disliked of the two political enemies. (Burr would kill Hamilton in a duel in 1803 by cleverly escalating a disagreement into a matter of honor.)

There were 16 states in 1800 (Ohio would join the Union as no. 17) and the nation’s population had grown to 5.3 million. Within weeks of becoming president, Jefferson learned that Spain had receded a large portion of its North American territory to France. Napoleon now owned 530 million acres, more than what the United States controlled. Fearful that losing control of New Orleans to our new French neighbor would lead to losing control of the strategically important Mississippi River, he developed a plan without including Congress.

He dispatched Robert Livingston and James Monroe to buy greater New Orleans for $10 million. They were pleasantly surprised when the French offered to sell 100 percent of their North American territories for $15 million cash … less several million in pending claims. Concerned that the French would change their offer before they could get formal approval, an agreement in principle was agreed to (later formally approved by Congress after James Madison’s assurance of its constitutionality.)

What a prize! 828,000 square miles for 3 cents an acre, virtually doubling the size of the United States and gaining control of the mighty Mississippi and shipping into the Gulf of Mexico. With this uncertainty removed, cotton production now expanded rapidly south and soon represented over 50 percent of total exports. With the aid of the cotton gin and slave labor, the United States now controlled 70 percent of the world’s production. Ominously, seeds of a great civil war were planted with each cotton plant.

For millions of people overseas, conquest or riches were not their primary ambition. Escaping the clutches of famine trumped all other hardships of life. 1842 was the first year in America’s history that more than 100,000 immigrants arrived in a single year. Five years later, the number from Ireland alone exceeded this, with Irish coming to America to escape the scourge of the Great Famine. In the 1840s and ’50s, 20 percent of the entire population of Ireland crossed the Atlantic in search of a better life. In sharp contrast to the Pilgrims on the Mayflower – who were on a financial venture supplied with rations – the Catholic Irish left in rags to avoid starvation in a mainly Protestant nation.

Concurrently, another wave from the European mainland was fleeing revolution and counterrevolution. In Germany, half-a-million left in a three-year period (1852-55) as a spirit of revolt captured the European continent. “We are sleeping on a volcano,” warned Alexis de Tocqueville. Meanwhile, two German thinkers (Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels) penned their intellectual nonsense, The Communist Manifesto, from the safety and luxury of London.

In the United States, just before the impending boomlet of immigration in 1846, total railroad mileage was a meager 5,000 miles. Ten years later, it quintupled to 25,000 as the influx of labor to lay iron rails was a perfect match for $400 million in capital. As famine and revolution were destroying Europe, their foreign transplants were busy transforming their new homeland. Also, the transition of coal to steam to steamboats scampering around the newly dug connecting canals would inspire new communications like the telegraph and Pony Express. While the country had been busy absorbing the wave of immigrants, it had also been in the throes of a decades-long internal migration west.

Thomas Jefferson had predicted it would be 1,000 years before the frontier reached the Pacific Ocean. Only 23 years after his death in 1826, gold was discovered in California and the fever to get rich started a westward movement that expanded globally. Once under way, the richness of the soil and massive new resources of rivers, forests, fish and bison would expand the migration to include farmers and their families. Horace Greeley shouted, “Go West, young man” and they did.

With room to grow and prosper, by 1900 the population would expand by a factor of 15 times to 76 million. They resided in 45 states after the Utah territories joined the Union in 1896. Fulfilling the vision of Manifest Destiny (from sea to sea), the rural population of 95 percent evolved as urbanization grew to 40 percent as industrialization and worker immigrants staffed the factories and cities. A short war with Mexico added California, Arizona and New Mexico, and President Polk’s annexation of Texas in 1845 filled in the contiguous states.

However, it was the railroads that created the permanence. With 30,000 miles of track in 1860, America already surpassed every other nation in the world. The continual growth was phenomenal: 1870 (53k), 1880 (93k), 1890 (160k) and by 1900 almost 200,000 … a six-fold increase in a mere 40-year period. Yes, there were problems: Illinois had 11 time zones and Wisconsin 38, but this was harmonized by 1883. Most importantly, they connected virtually every city and town in America and employed 1 million people!

Throw in a few extras like electricity, oil wells, steel mills and voila! The greatest nation ever built from scratch. Today, we have 6 percent of the people on 6 percent of the land and 30 percent of the world’s economic activity … and we are celebrating the 50-year anniversary of putting a man on the moon.

Do we still have “the right stuff” to continue this remarkable story? I say definitely, if we demand that our leaders remember how we got here.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].