By Jim O’Neal

We often fail to remember that history (itself) has a history. From the earliest times, all societies told stories from their past, usually imaginative tales involving the acts of heroes or various gods. Later, civilizations kept records inscribed on clay tablets or the walls of caves. However, ancient societies made no attempt at verification of records, and often failed to differentiate between reality and mythical events and legends.

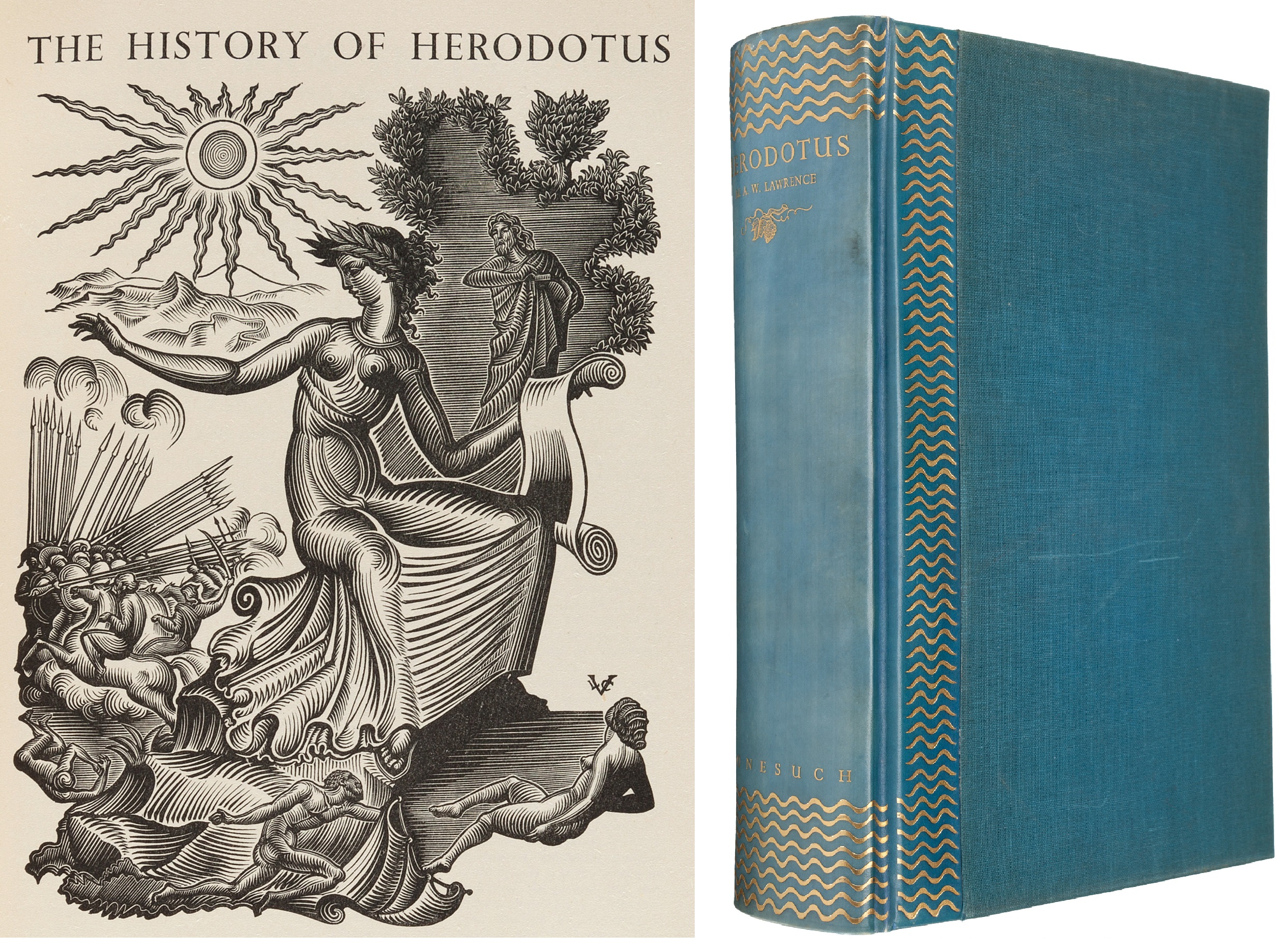

This changed in the 5th century B.C. when historians like Herodotus and Thucydides explored the past by the interpretation of evidence, despite still including a mixture of myth (“history” means “inquiry” in Greek). Still, Thucydides’ account of the Peloponnesian War satisfies most criteria of modern historical study. It was based on interviews with eyewitnesses and attributed actual events to individuals rather than the intervention of gods.

Thus, Thucydides managed to create the most durable form of history: the detailed narrative of war, political conflict, diplomacy and decision-making. Then, the subsequent rise of Rome to dominance of the Mediterranean encouraged other historians like Polybius (Hellenic) and Livy (Roman) to develop narratives to capture a “big picture” that made sense of events on a longer time frame. Although restricted to just the Roman world, it was the beginning of a universal history to describe progress from origin to present, with a goal of giving the past a purpose.

In addition to making sense of events through narratives, there was a tradition growing to examine the behavior of heroes and villains for future moral lessons. We still attempt this today with a steady stream of studies of Lincoln, Churchill and Gandhi, as well as Stalin, Hitler and Mao.

But there was a big hiccup with the rise of Christianity in the late Roman Empire era, which fundamentally changed the concept of history in Europe. Historical events started to be viewed as “divine providence” or the working of God’s will. Skeptical inquiry was usually neglected and miracles routinely accepted without question. Thankfully, the Muslim world was more sophisticated in medieval times and they rejected accounts of events that could not be verified.

However, neither Christians nor Muslims produced anything close to the chronicle of Chinese history published under the Song Dynasty in 1085. It recorded history spanning almost 1,400 years and filled 294 volumes. (I have no idea how accurate it is!)

By the 20th century, the subject matter of history – which had always focused on kings, queens, prime ministers, presidents and generals – increasingly expanded to embrace common people, whose role in historical events became more accessible. But most world history was written as the story of the triumph of Western civilization, until the second half when the notion of a single grand narrative simply collapsed. Instead, the post-colonial, modern world demanded the study of blacks and women’s histories, in addition to Asians, Africans and American Indians.

Now we are in another new place where it is increasingly difficult to know where to find reliable accounts of real events and a flood of “fake news” is competing for widespread acceptance. Maybe Henry Ford was right after all when he declared that “History is bunk!”

Personally, I don’t mind and still enjoy frequent trips to the past … regardless of factual flaws.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].