By Jim O’Neal

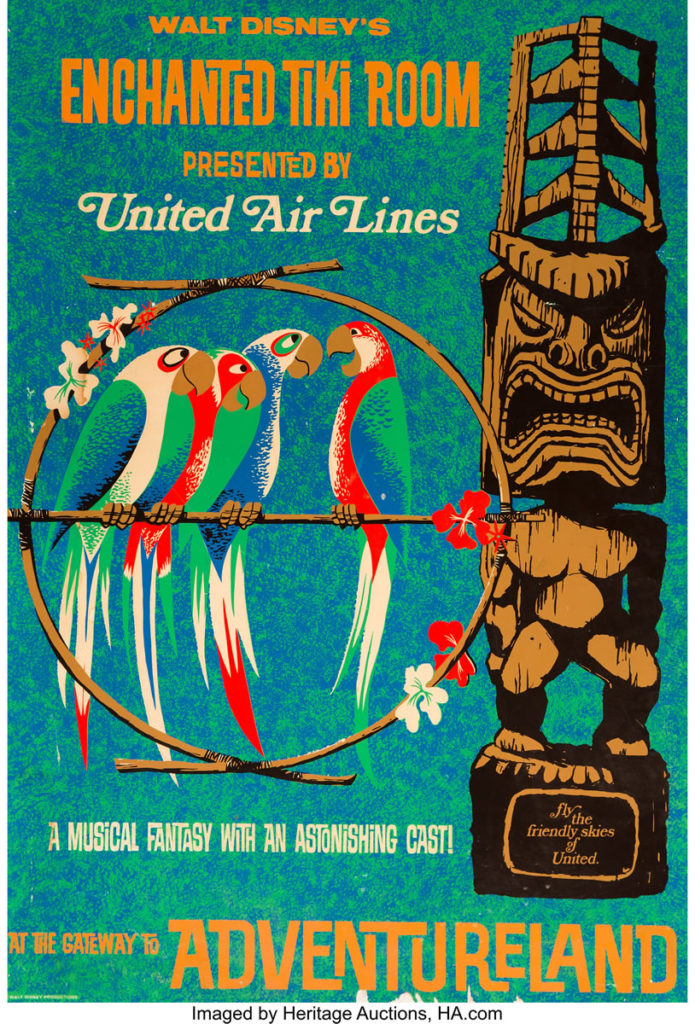

On Sunday, July 17, 1955 the first Disneyland opened in Anaheim, CA. The $17 million theme park fit nicely on 160 acres of orange groves, and the 13 attractions were designed with the whole family in mind. Opening day was intended for special guests and a crowd size of 15,000. However, the $1 admission tickets were heavily counterfeited and over 28,000 people overwhelmed the Park.

Ronald Reagan, Art Linkletter, and Bob Cummings co-hosted the ABC TV coverage of the event and 70 million people tuned in from home. It was an unusually hot day and Harbor Blvd. had a line of cars seven miles long, filled with parents and kids yelling the usual questions and in need of a rest stop. Later, the Park inevitably ran out of food and water (the plumbing wasn’t finished). Pepsi Cola was readily available, and the publicity was not good (some even implied it was a conspiracy). The day grew in notoriety and soon became known inside Disney as “Black Sunday”. But, within a matter of weeks all the start-up kinks were resolved, and it has been a crowd pleaser ever since.

Although the details are sketchy, 33 local companies (e.g. Carnation, Bank of America, Frito-Lay, etc.) were charter members which helped Disney with the financing and infrastructure involved. Eventually, this evolved into a “Club 33” which included access to an exclusive fine-dining restaurant that serves alcoholic beverages (the only place in the Park). Today there’s a 5-10 year waiting list for companies or individuals eager to pony up $25,000 to have the privilege of paying 6-figure annual dues. There are several versions of the origin of the Club 33 name. One is rather obvious and another involves the California Alcohol Beverage Control regulations that requires a real address in order to have alcohol delivered. Go figure!

Irrespective of the fuzzy facts, when I joined Frito-Lay in 1966, F-L operated Casa de Fritos, a delightful open-air Mexican food restaurant. Visitors could enjoy a family friendly sit-down lunch/dinner or get a Taco Cup to go. The Cup served as a one-handed snack and was easily portable while strolling around the park. Casa de Fritos was managed by a pleasant man named Joe Nugent, who had only one obvious weakness. Casa de Fritos was too profitable!

Let me briefly explain.

Once a year the Flying Circus from Dallas came out to the Western Zone to review our Profit Plan for the next year. President Harold Lilley – who was very direct with few words – would publicly berate poor Joe. ”Dammit, Joe, I told you we didn’t want to make any money at that Mexican joint. We want to promote Fritos corn chips so people will buy them at their local supermarket!”. When I asked Joe about it, he said he had tried increasing the portion sizes and also lowering the menu prices. But, whenever he did even more people would line up to get it. This man may have invented volume price leverage and never had a clue what he was doing!

Soon the VP/GM for SoCal – George Ghesquire – finally convinced the wise men in Dallas to let us test market restaurant style tortilla chips (RSTC). He had grown weary of seeing bags of Fritos over in the Mexican food section. It was proof that someone had initially purchased Fritos, then changed their mind and swapped it for a bag of restaurant style tortilla chips. Dallas had previously been concerned that RSTC would cannibalize sales of Fritos and they were absolutely right. However, the delicious irony was that it was being done by our direct competition!

So our version of RSTC was finally being authorized and would have a brand name of Doritos (you may have seen it). It was to be a 39 cent 6 oz. bag and everyone was eager to get started. To ensure a fast start we loaned some money to Alex Morales the owner of Alex Foods – the supplier of the Taco Cup – and a contract to co-pack. It started with one truckload a week, but they were soon running around the clock. The product was so popular in the West/Southwest that a line had to be added to a plant in Tulsa and the new plant in San Jose. The world of Frito-Lay would never be the same.

To compensate for the lack of salsa, we made a quick trip to a local Vons supermarket and bought some bags of Lawry’s taco seasoning (used in homes to season the meat while preparing homemade tacos for dinner)…voila Doritos Taco flavored chips. Roy Boyd “Mr. Fritos” from Dallas helped us equip Alex Foods with 2 cement mixers from Sears and a handheld oil sprayer to keep the taco powder adhering to the chips.

Now flash forward to 1973 and I was entering my office on the 4th floor of the Frito-Lay Tower near Love Field in Dallas. I noticed a large plastic bag filled with tortilla chips. When I asked Roy, he explained it was a new flavor being evaluated for test market. After tasting 2-3 chips I remember saying “Naw…too dry”. Soon it would become Doritos Nacho flavored tortilla chips, one of the most successful new food products in the later quarter of the 20th century!

Looking back, I now realize that’s probably when I became one of the wise men in Dallas.

The next year (1974) Harry Chapin would sing about the “Cat’s in the cradle” which would earn him a Grammy nomination and eventually a place in the Hall of Fame (2011). I’d nominate the obscure, long forgotten, George Ghesquire for the Frito-Lay Hall of Fame, but I don’t think we have one. So until we do, maybe just “Father of Doritos “. The Crown that now rests with Arch West who absconded with it when he left the Company in 1968.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].