By Jim O’Neal

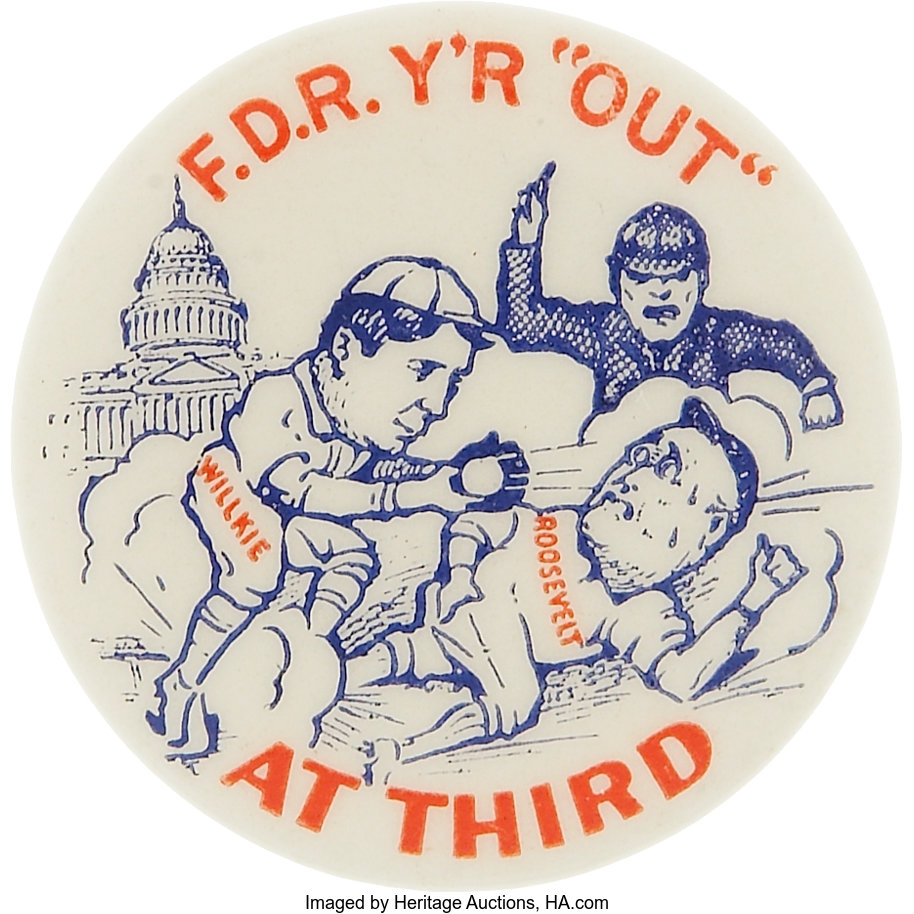

On Sept. 19, 1940, loyal hard-core supporters of the New Deal awoke to a rather startling surprise. The venerable editorial gurus at The New York Times announced their choice for the upcoming presidential election … and it was not Franklin Delano Roosevelt!

The Times had supported FDR in 1932 and 1936, but in 1940, they decided to support his Republican opponent, Wendell Willkie. In rationalizing this decision, they prepared a long preamble describing the seriousness of national and world affairs, but without offering anything new that was not already common knowledge: “One of the great crises in American history … a hostile force sweeping across Europe … impossible to continue isolation … world revolution at stake … Americans fortunate to have two candidates who agree on fundamental foreign policy.”

To buttress their choice of Willkie, they asserted he was better equipped to provide the country with an adequate national defense. They described him as a practical liberal who understood the need for increased production and, lastly, because the fiscal policies of Roosevelt had failed disastrously. And, as a coup de grâce, it was their belief that the traditional safeguards of democracy were failing everywhere. They did not mention that Willkie was a corporate lawyer, read Marx and lobbied for his college to teach socialism. They also failed to mention that Fortune magazine had dedicated an entire edition to Willkie.

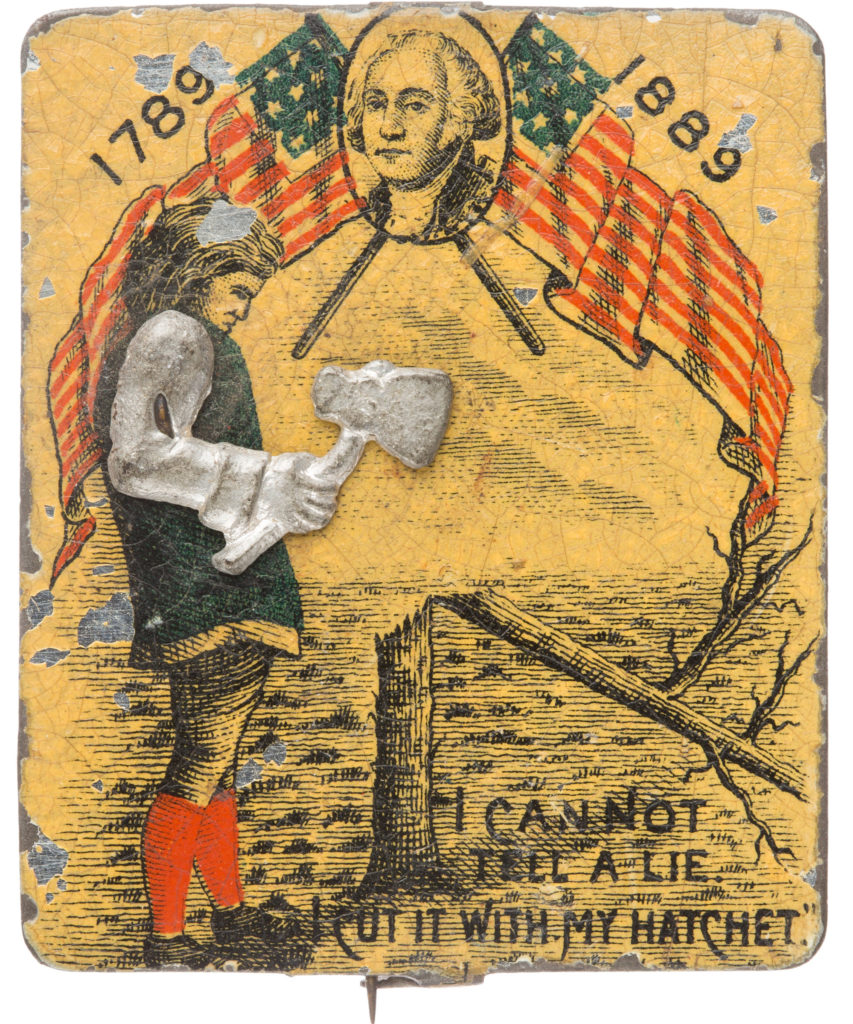

Instead, they added to this litany the old third-term taboo, a principal that dated to George Washington. Perhaps they didn’t realize that Washington was too sick to serve a third term (he would die the following year) or that Thomas Jefferson turned down a third term for purely precedent-setting political reasons.

But The Times conceded that FDR had a taken a number of steps to bolster defense, including the new Defense Advisory Commission, before quickly deriding it for lack of real power (it had become a mere consultancy) unable to cut through Washington’s red tape. Instead, they much preferred Willkie’s call for individual sacrifice, hard work and “sweat and toil.” They found this more reassuring than Roosevelt’s speeches, designed to maintain morale. In essence, they were charging the president with a lack of substance.

In choosing Willkie, they were arguing for a business leader with practical experience in stimulating economic growth, while expanding industrial production. “In this field, Willkie is the professional and Mr. Roosevelt the amateur.” A harsh indictment of the country’s leader!

Then the NYT in its editorial proceeded to excoriate FDR for fiscal policy (under an argument it titled “The Road to Bankruptcy”) by highlighting three specific policies that had become reckless:

● A silver policy that had grown to incredible proportions. They cited more than 2 billion ounces of silver – “which our government has no earthly use” – purchased by the Treasury “at overvalued prices in an artificial market. This policy makes no sense, except as a political maneuver.”

● A national debt that had doubled in seven years.

● Welfare programs that would lead citizens to bed rather than work.

In retrospect, we know the NYT was wrong on many levels. Collectively, the New Deal kept the country together through the entirety of the two greatest travails ever visited on the United States. Times were tough and sacrifices many, but we emerged with our republic intact. Roosevelt proved himself tough enough to steer our ship through rough and dangerous waters.

The economic and social reforms of the New Deal created a legacy of new solutions, from the Works Progress Administration and Social Security to banking and financial regulations and a modicum of security to millions of people who’d never tasted it. FDR managed to impart a freedom from fear that resulted in a platform to take on the sacrifices of the impending war.

We ramped up a massive display of Americanism. The Selective Service Act established the first peacetime conscription in U.S. history, while Rosie the Riveter galvanized generations of women as factory workers, warriors and healers … all keeping the home safe. The stimulus from war production produced a Keynesian effect that wiped out the lingering depression.

Thanks to the strategic blunder of Dec. 7, 1941, we saved the free world and possibly civilization as well. Starting with a “Germany First” strategy (whereby the United States and the United Kingdom agreed to subdue Nazi Germany first), Americans gradually led the world back to peace and, in the process, became the Peace-Keeper-Rebuilder.

Perhaps for the first time in modern history, conquering armies did not take vast territories or treasure. We brought our troops home and resumed the American story.

The world owes America a debt that has long been forgotten.

A little-known postscript: FDR and Willkie discussed starting a new liberal party to supplant Republicans and Democrats. Willkie died before the idea had a chance to become a reality, but it’s fun to contemplate how different things might be today.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].