By Jim O’Neal

This is a highly condensed story of an American retailing giant that only seems relevant as just another casualty of internet e-tailing. In cultural terms, it is generally portrayed as just another backwater wasteland. But this situation seems oddly different, since it seems like Sears has been a central player in the story of American life.

For a long time, the retailer’s products, publications and people influenced commerce, culture and politics. And then, slowly, it became subsumed into the gravitational pull of business bankruptcies that is relentless when corporate balance sheets weaken and finally fail. I selected it – rather than, say, Montgomery Ward, Atlantic & Pacific, or J.C. Penney – because of its long history and because its demise was like losing a century of exciting surprises to an indifferent bankruptcy judge who yawned and gaveled it into the deep, dark cemetery of obscurity.

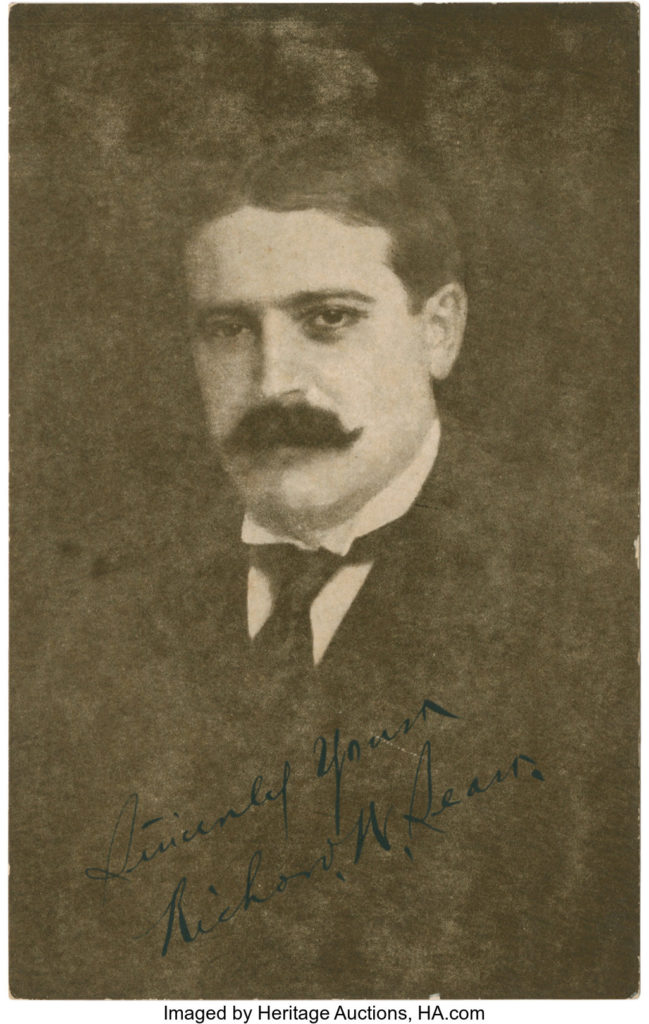

Sears has roots to 1886, when a man named Richard W. Sears began selling watches to supplement his income as a railroad station agent in North Redwood, Minn. The next year, he moved the business to Chicago and hired Alvah C. Roebuck, a watchmaker, through a classified ad. Together, they sold watches and jewelry. The name was changed in 1893 to Sears, Roebuck & Company and by 1894, sewing machines and baby carriages were added to its flourishing mail-order business. Its famous catalogs soon followed.

Sears & Roebuck helped bring consumer culture to middle America. Think of the isolation of living in a small town 120 years ago. Before the days of cars, people had to ride several days in a horse and buggy to get to the nearest railroad station. What Sears did was make big-city merchandise available to people in small towns, desperate for news and yearning for new things. It made hard work worthwhile knowing that there was a surprise just over the horizon.

The business was transformed when Richard Sears harnessed two great networks – the railroads, which now blanketed the entire United States, and the mighty U.S. Postal Service. When the Postal Service commenced rural free delivery (RFD) in 1896, every homestead in America came within reach.

And Richard Sears reached them!

He used his genius for promotion and advertising to put his catalogs in the hands of 20 million Americans, at a time when the population was 76 million. Sears catalogs could be a staggering 1,500 pages with more than 100,000 items. When pants supplier and manufacturing wizard Julius Rosenwald became his partner, Sears became a virtual, vertically integrated manufacturer. Whether you needed a cream separator or a catcher’s mitt, or a plow or a dress, Sears had it.

The orders poured in from everywhere, as many as 105,000 a day at one point. The company had so much leverage that it could nearly dictate its own terms to manufacturers. Suppliers could flourish if their products were selected to be promoted. Competition was fierce and the Darwinism effect was in full play. Business boomed as the tech-savvy company built factories and warehouses that became magnets for suppliers and rivals as well. City officials complained that it was harming nearby small-town retailers (sound familiar?).

There was a time when you could find anything you wanted in a Sears catalog, including a house for your vacant lot. Between 1906 and 1940, Sears sold 75,000 build-from-a-kit houses, some still undoubtedly still standing. The Sears catalog was second only to the Holy Bible in terms of importance in many homes.

In 1913, the company launched its Kenmore brand, first appearing on a sewing machine. Then came washing machines, dryers, dishwashers and refrigerators. As recently as 2002, Sears sold four out of every 10 major appliances, an astounding 40 percent share in one of the most competitive categories in retailing.

By 1925, they opened a bricks-and-mortar retail store in Chicago. This grew to 300 by 1941 and more than 700 in the 1950s. When post-war prosperity led to growth in suburbia, Sears was perfectly positioned to cash in on another major development: the shopping mall. A Sears store was an ideal fit for a large, corner anchor store with plenty of parking. Sears revenue topped $1 billion for the first time in 1945 and 20 years later it was the world’s largest retailer and, supposedly, unassailable.

Oops.

By 1991, Walmart had zipped by them … never bothering to pause and celebrate. For generations, Sears was an innovator in every area, including home delivery, product testing and employee profit-sharing, with 350,000 dedicated employees and 4,000 outlets. What went wrong?

The answer is many things, but among the most significant was diverting their considerable retail cash flow in an effort to diversify. Between 1981-85, they went on a spending spree, first acquiring Dean Witter Reynolds, the fifth-largest stock brokerage, and then real estate company Coldwell Banker. They ended up selling the real estate empire and then spun off Dean Witter in a desperate effort to return to their retailing roots. This was after someone decided to build a 110-story, 1,450 foot skyscraper with 3 million square feet (the tallest building in the world at the time) to centralize all their Chicago people and then lease whatever was left over. You have to wonder what all these people were doing. (It wasn’t selling perfume or filling catalog orders!). The Sears Tower is now called Willis Tower (don’t ask).

They stopped the catalogs in 1993. One has to speculate what would have happened had they simply put their entire cornucopia of goodies online. I know timing is everything, but in 1995, on April 3, a scientist named John Wainwright bought a book titled Fluid Concepts and Creative Analogies: Computer Models of the Fundamental Mechanisms of Thought. He purchased it online from an obscure company called Amazon.

I will miss Sears when they gurgle for the last time. I cherished those catalogs when we lived in Independence, Calif. (the place Los Angeles stole water from via a 253-mile aqueduct). Me and my Boy Scout buddies all made wish lists, while occasionally sneaking a peek at the lingerie section.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].