By Jim O’Neal

“The whole country is in a state of agitation upon the approaching presidential election such as was never before witnessed. … Not a week has passed within the last few months without a convocation of thousands of people to hear inflammatory harangues. Here is a revolution in the habits and manners of the people. Where will it end? These are party movements, and must in the natural progress of things become antagonistic … their manifest tendency is to civil war.”

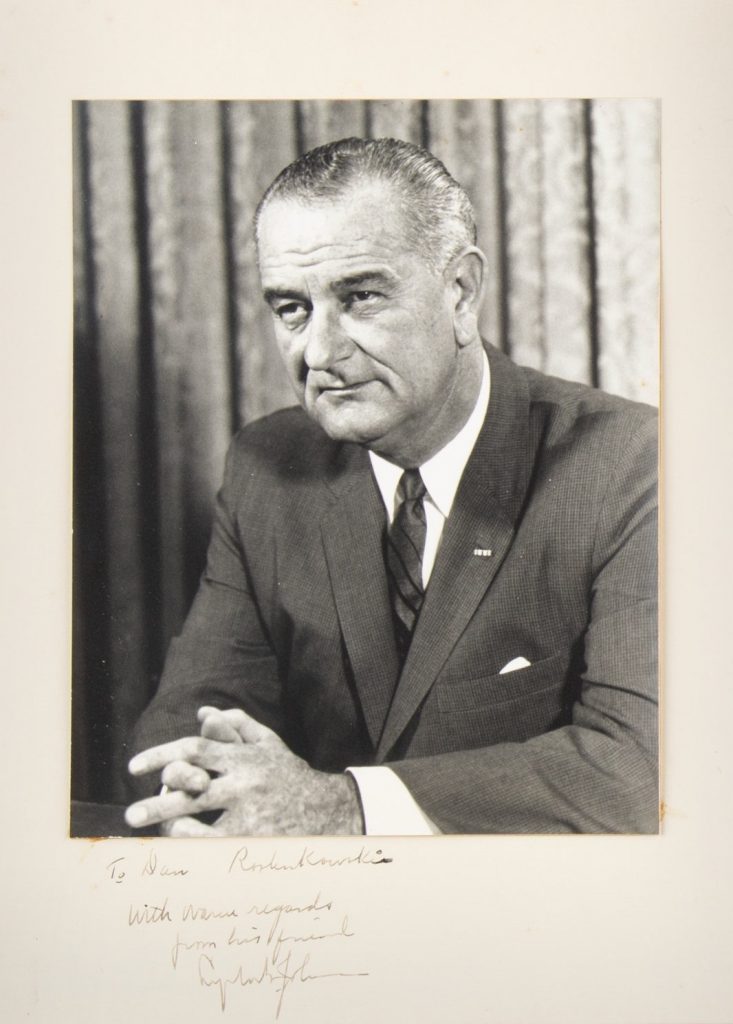

If you guess this was 1964 when LBJ was set to defeat Barry Goldwater, you would be wrong. Or perhaps 1992 when Bill Clinton and Ross Perot were trying to unseat President George H.W. Bush? Sorry. You’re not even in the right century! We’re in a much earlier time, a time without 24/7 cable news and its insatiable appetite for divisive issues coupled with scores of political partisans eager to share their opinions. A time when you could not discern political bias by simply knowing the TV channel.

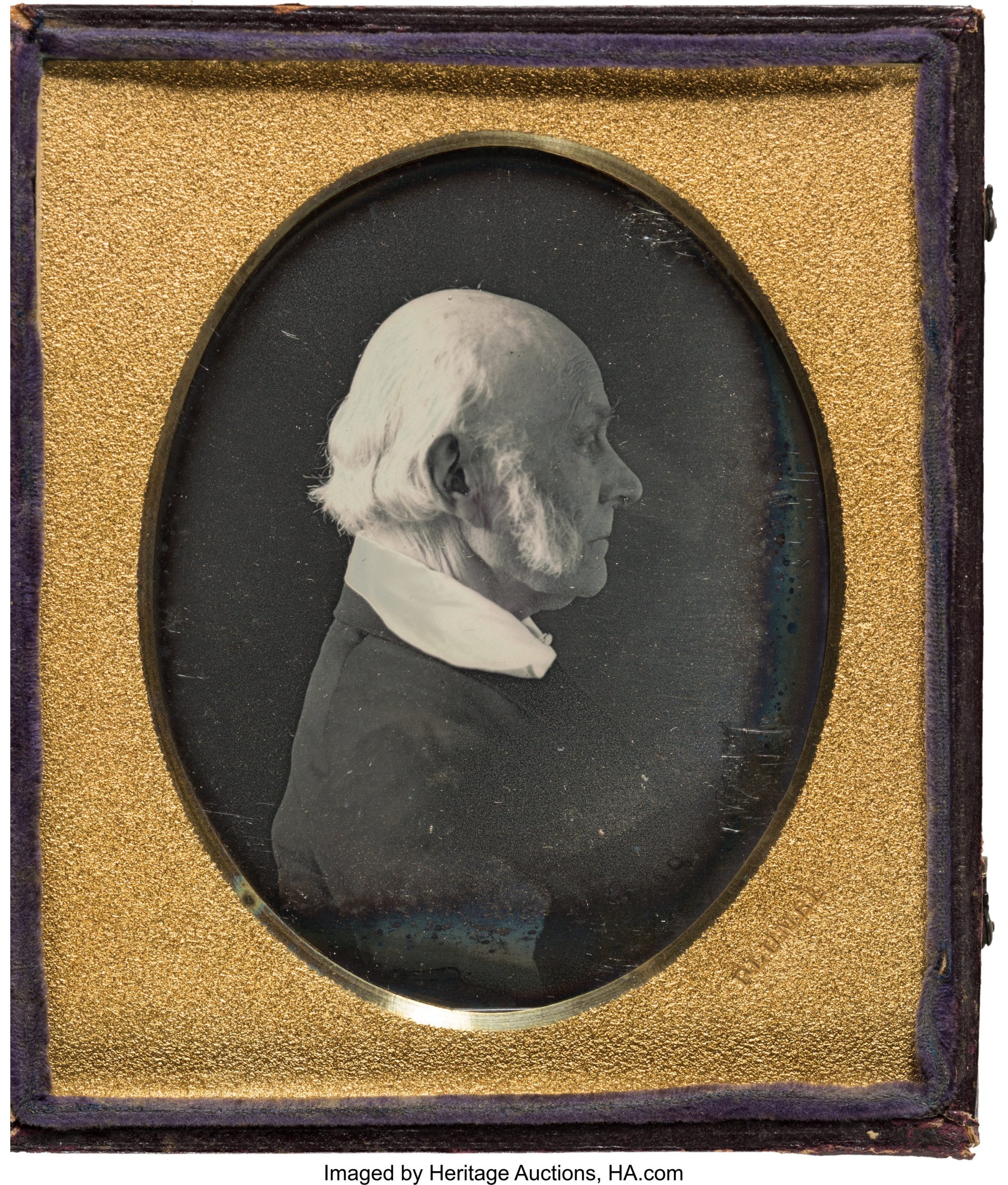

The year was 1840 when the Whigs were trying to oust President Martin Van Buren from the White House. It was a boisterous time and the speaker was ex-President John Quincy Adams (1767-1848). These words come from a concerned man, but then again, political speeches were more impassioned than we’ve ever heard in our lifetimes.

Eight years later, Congressman JQA, representing Massachusetts, rose in the House of Representatives to speak, but suddenly collapsed on his desk. He died two days later from the effects of a cerebral hemorrhage in the Speaker’s chambers. The public mourning that followed exceeded, by far, anything previously seen in America. Forgotten was his failed one-term presidency, routinely cold demeanor, cantankerous personality, and even the full extent of his remarkable public life.

For two days, the remains of our sixth president (and son of the second president) reposed in-state while an unprecedented line of thousands filed through the Capitol to view the bier. On Saturday, Feb. 25, funeral services began in the House. After all the speeches, and after a choir had sung, the body was escorted by a parade of public officials, military units and private citizens to the Congressional Cemetery. After the coffin remained in a temporary vault for several days, 30 members of Congress, one from each state, were ready to accompany it on the 500-mile railway journey to Boston. The train, with a black-draped special car, traveled for five days through a cloud of universal grief. The caravan stopped often to permit local ceremonies and citizens to stand in silent tribute.

Boston greeted his remains by exhibiting the insignia of mourning virtually everywhere. On March 12, every prominent politician in Massachusetts vied to join in escorting the casket to Quincy’s First Parish Church, where Pastor William Lunt delivered a moving sermon that ended with “Be thou faithful until death, and I will give thee a crown of life.” Later, Harvard President Edward Everett (of Gettysburg fame) eulogized JQA for two hours in the presence of the Massachusetts legislature, which had gathered in Faneuil Hall.

Only Abraham Lincoln’s death evoked a greater outpouring of national sorrow in the entire 19th century in America.

Eventually, JQA’s coffin was installed in a monumental enclosure with his mother Abigail to his right and his wife Louisa to his left. With the inclusion of his father, John Adams, it has become a national shrine; unique in America’s history since it marks the graves of two presidents of the United States and two First Ladies.

And what of the man who had been secretary of state and vice president for Andrew Jackson and was now trying to win another term as president? Martin Van Buren (1782-1862), the “Wizard of Kinderhook,” was surprisingly short at 5-6, and had been elected in 1836 when Jackson decided against a third term and threw his support to Van Buren.

The opposing Whigs were too divided to hold a national convention in 1836 since they couldn’t agree on a single candidate. Instead, they adopted a clever plan to support regional favorite sons with the hope they could deny Van Buren an electoral victory, force the election into the House of Representatives (as in 1824) and then unite behind a single Whig candidate to secede Jackson. The anti-Van Buren press was vitriolic and the New York American called him “illiterate, sycophant and politically corrupt.”

Van Buren remained implacable and on election day racked up 764,195 votes (50.9 percent) and his three Whig opponents were left to carve up the remainder. New York power broker and publisher Thurlow Weed summed it up succinctly: “We are to be cursed with Van Buren for president.”

However, on May 10, 1837 – only two months after the new president took office – prominent banks in New York started refusing to convert paper money into gold or silver. Other financial institutions, also running low on hard currency, followed suit. The financial crisis became the Panic of 1837. This was followed by a five-year depression that forced bank closures, economic malaise and record unemployment. Now flash forward to 1840, when Van Buren easily won re-nomination at the Democratic National Convention despite the economic woes. But the government was also mired down with major divisive issues: slavery, westward expansion, tension with Great Britain. Van Buren had not recognized what James Carville would memorialize 150 years later: “It’s the economy stupid!”

Other financial panics would continue to plague the country periodically until 1913, when President Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act. These wizards can create money out of thin air by using an electronic switch that coverts ions into gizmos that people will buy with money that is guaranteed by the federal government.

What’s in your wallet?

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].