By Jim O’Neal

The results from my 2001 annual physical indicated one area of concern: an elevated PSA. These three letters represent an enzyme (prostate-specific antigen) and, with a digital rectum exam, can indicate three possibilities. One is prostate cancer. Early detection – as with most diseases – can dramatically improve the odds for a cure. So my next logical step was a visit to a local urologist.

An eight-needle biopsy (they used to take six) confirmed the presence of cancer. Pathologists use a grading score derived by peering through a microscope at images to assess cell-differentiation on the left and right of the prostate. Each are ranked 1 to 5 and then added together. My Gleason was 3/4, which is higher than the 3/3 of an average prostate cancer. But, it did not reveal how fast the cancer was growing or if it had managed to escape from the prostate. Prostate cancer seems compelled to get in the main blood stream and then find a safe place to hide and grow. As you can appreciate, this is not a good thing, so the objective is to get it out permanently asap.

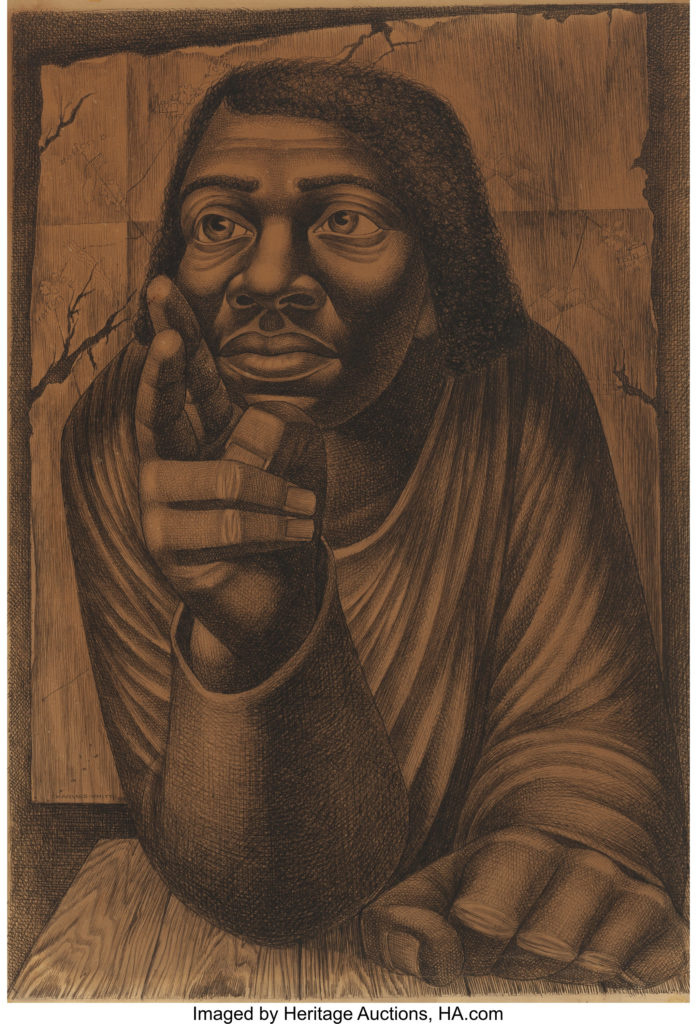

Prostate cancer is a diabolical opponent and in 2000, 180,000 American men were positively diagnosed and 32,000 died. It can be caused by hereditary and African-Americans have a higher incidence. However, the Western diet … lots of fat, red meat, pizza and even Cheetos … is, in my view, the real scoundrel when compared to Asia. Curing it is highly dependent on several variables, but the two most important are the skill of the surgeon and having the cancer still contained in the organ.

I was able to get an appointment with Dr. Patrick Walsh at Johns-Hopkins and Nancy and I flew to Baltimore on June 3. Dr. Walsh is a quiet, serious man, but with a great sense of humor and compassion. He is unlike most surgeons who tend to have a swagger, in my opinion, and invariably a sense of urgency (possibly because they’re on a mission to save the world) and prefer talking. Dr. Walsh quietly listened and then whisked my slides away to evaluate two things. First, he confirmed I had cancer and second, he thought I’d be a good candidate for a radical (his specialty and the only reason we were there).

One small detail was his availability. The first opening wasn’t until Sept. 5 (after a governor, two senators and the King of Spain, among others). It was a long summer.

After a successful operation, I was recuperating in Baltimore and watching CNN when the first plane hit the World Trade Center. My physical situation seemed trivial compared to the 9/11 chaos in NYC and the future implications. We were at war.

I had a lot of time to read and the words “the skill of the surgeon,” which guided me to the history of this noble profession. In 1536, during one of the perpetual wars between France and Spain, French soldiers invaded the Italian city of Turin after a bloody battle. The conventional wisdom was that bullet wounds should be cauterized with boiling oil. A French surgeon ran out oil and substituted a milder concoction of egg yolks, oil of roses and turpentine. The next day, the men treated with boiling oil were in great agony, while the others with bland dressings were resting comfortably. It seems modern surgery began with a great unlearning of quackery, some of it dating back 2,000 years. Western medicine was based on the teaching of Hippocrates and it was sadly out of date as the boiling oil example typifies.

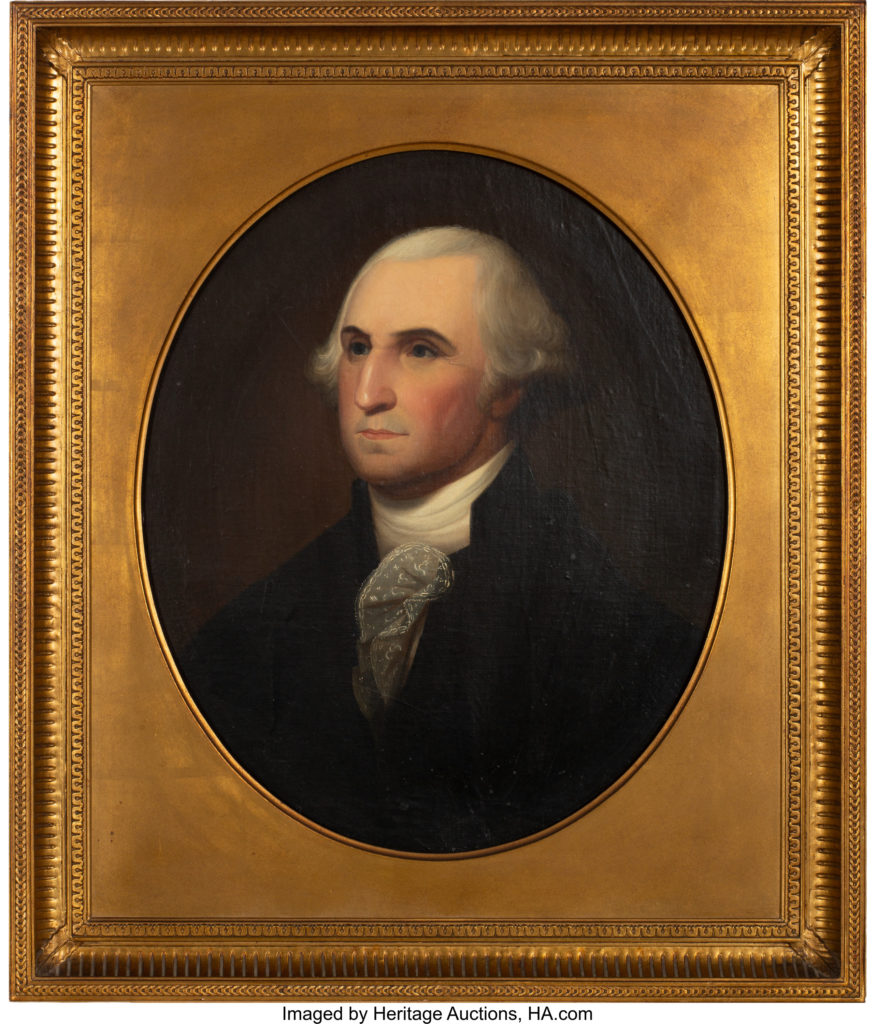

Alas, other examples abound: Critically ill and dehydrated patients were given noxious potions to provoke vomiting and diarrhea. Other patients died regularly after being bled by leeches and lancets. George Washington went to bed with a severe sore throat and died eight hours later after four doctors drained 40% of his blood. One historian wrote, “If Hippocrates is the Father of Medicine, it is a dubious paternity.”

Operations were once compared to commando raids. Surgeons get in and out with maximum haste, while cutting off as few of their assistants’ fingers as possible. Then there was the enormous, rather obvious, but unrecognized significance of sterility. Most surgeons never stopped to change their gowns, wearing the blood-soaked garments as a badge of endurance while operating on a conveyor of multiple patients. Hospitals developed a well-earned reputation as houses of death.

Another startling example occurred in the middle of the 17th century when new mothers (in hospitals) started dying in droves all over Europe. The mysterious disease was dubbed puerperal (Latin for child) fever. Doctors attributed it to bad air or lax morals. In fact, it was due to germ-laden hands transferring microbes from one uterus to another. A doctor in Vienna, Ignaz Semmelweis, realized that if hospital staff washed their hands in mildly chlorinated water, deaths of all kinds declined sharply. It took 250 years for the medical profession to recognize the influence of hygiene on patient mortality. It seems morbidly ironic that we’re still preaching about hand washing in the middle of a pandemic or arguing if face masks are some secret Constitutional right.

I was blessed. Before the 1980s, 100% of men who had prostate surgery were impotent and probably severely incontinent. Dr. Walsh told me that many men felt the cure was worse than the disease. Then, he (personally) discovered a remarkable fact. The nerves were outside the prostate and potency could be preserved if a highly skilled surgeon performed the delicate surgery. He perfected the “nerve-sparing” technique that has permitted millions of men to maintain a normal family life. Pass the pizza. We’ve removed another barrier to dietary freedom!

I hope it’s not too long before another writer looks back at the present time and explains why 100% of Americans didn’t get a simple vaccination that would have prevented some of us from joining the nearly 600,000 people who have died or the 32 million that got COVID-19. Herd immunity seems like such an easy objective, but if the African variant mutates and we need a new vaccine … well you get the drift.

I’m honestly embarrassed by the utter stupidity.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].