By Jim O’Neal

It is difficult, and bordering on impossible, to construct a list of the “Seven Wonders of the World” since they seem to be moving targets, subject to frequent revisions and disagreements between people who claim to have a personal degree of expertise. However, it is feasible to build a reasonable consensus on the “Seven Wonders of the Ancient World” … if one starts with the list compiled by Greek engineer Philo of Byzantium in 225 B.C.

It seems mildly comforting that at one time in the distant past, humans created structures that were worthy as works of gods, and ancient travelers could make a “bucket list” if they were inclined to participate in this more modern concept. Here is the list for any intrepid adventurous souls.

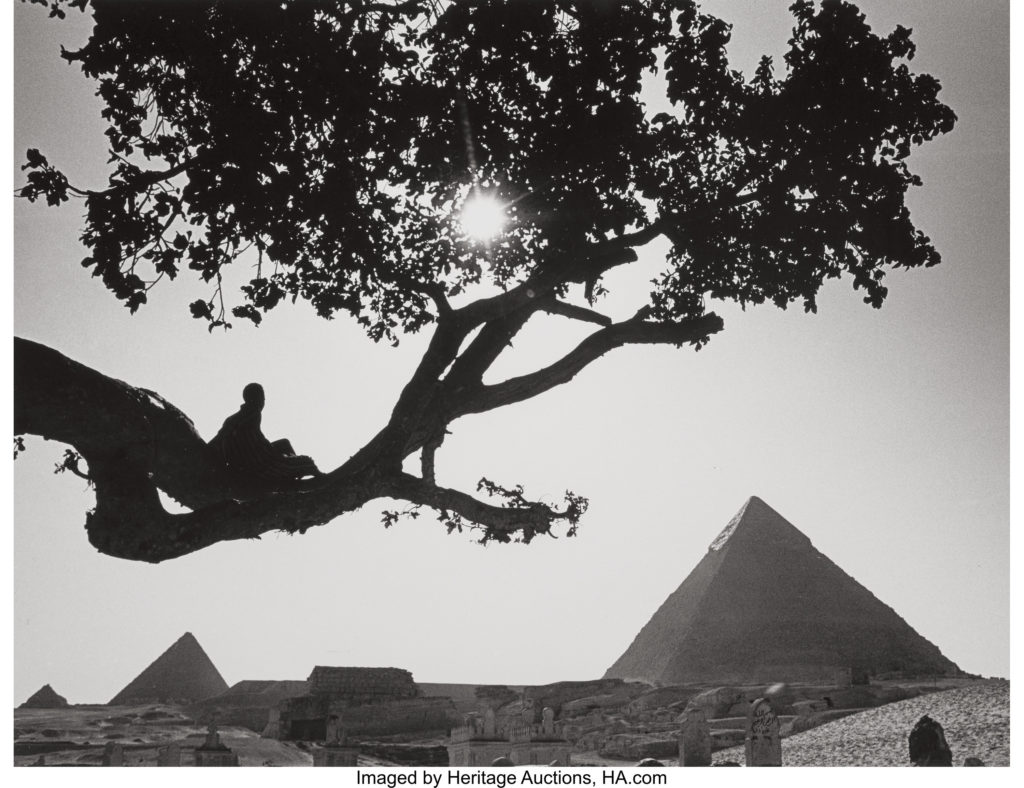

- The Great Pyramid of Giza: Constructed about 4,600 years ago for the Egyptian Pharaoh Khufu (known as Cheops to the Greeks). Just outside of modern Cairo, it was the tallest manmade structure on Earth for roughly 4,000 years. It is the only one still standing and I can personally verify it’s still there. Despite centuries of erosion, it’s still about 450 feet high and consists of 2 million blocks weighing 2½ tons each. Somehow, its builders were able to align it in a perfect square with the four cardinal points on the compass. If you ever decide to hunt for signs of extraterrestrial activity, this would be a good place to start!

- The Hanging Gardens of Babylon: Assuming this ancient wonder actually existed, King Nebuchadnezzar II built it nearly 3,000 years ago near the Euphrates River (when Babylon was the capital of a great empire) to appease his wife Amytis, who was homesick for the hills of Persia. Besides the Gardens, Neb II is notorious for capturing and destroying Jerusalem circa 597 B.C.

- The Statue of Zeus at Olympia: Zeus was the mightiest Greek god (adopted by the Romans as Jupiter) and this 40-foot statue was carved with Zeus on a cedar throne with ivory and gold skin. Roman Emperor Theodosius had it relocated to Constantinople, where it was destroyed by fire in 475 A.D.

- The Temple of Artemis at Ephesus: Built to honor the daughter of Zeus and sister of the sun god Apollo. By reputation, the most beautiful of the ancient wonders since it was funded by King Croesus of Lydia (modern Turkey). With 127 marble columns, historians have said it “surpassed every structure ever raised by mortal men.” Ephesus is a very delightful ancient port city and on everyone’s itinerary for this area.

- The Tomb of King Mausolus at Halicarnassus: Queen Artemisia built this to honor her husband or brother or both (accounts vary). Obviously, the source of the word “mausoleum.” I thought I had been to all the major cities in Turkey, but Bodrum is new to me.

- The Colossus of Rhodes: My kind of wonder. The Colossus represents Apollo … towering over the harbor of Rhodes after the war between Rhodes and Macedon (Greek). Some myths compare it to the Statue of Liberty in the New York harbor. The great Roman historian Pliny wrote about pieces still there in the first century A.D.

- Lighthouse of Alexandria: Also known as the Pharos off the coast of Egypt; for centuries it was one of the tallest manmade structures in the world. It’s long gone (its last stones were apparently used for other projects in the 1400s), but very plausible, since Alexandria was the world’s cultural capital after being founded by Alexander the Great.

Obviously, the Greek writers and historians who recorded these events and wonders could only include what was in their part of the world, thus pre-Christian wonders were excluded. The most prominent, in my view, not included was the Great Wall of China, the longest fortification and possibly the greatest project ever undertaken. Much of the present wall dates from 1420 A.D. when the Ming Dynasty enlarged it. Its origins date back 1,600 years to earlier dynasties to protect the northern frontier; this was a 1,400-mile effort utilizing 300,000 laborers.

Also ignored was the entire city of Persepolis, the capital of Persia, probably intentionally because of their intense dislike by the Greeks. In 1971, the Shah of Iran staged an enormous celebration in the ruins of Persepolis to commemorate its 2,500th anniversary (yes, the same shah who was overthrown in 1979).

We live on a terribly small planet, but we have a marvelous historic record to pore over … facts, myths and fables that tend to become blurred over time. This is one problem our generation won’t have. I suspect 100 percent of the entire world’s sounds and activities will soon be on either a smartphone, bodycam or other device for permanent transfer and storage on YouTube.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].