By Jim O’Neal

Our war with Japan formally ended on September 2, 1945. A week earlier, the battleship Missouri had slipped into Tokyo Bay and anchored where Commodore Matthew Perry had sailed four warships in 1853 to open up trade with Japan. Since the 1600s, Japanese rulers had refused to engage with the outside world. Perry’s Kanagawa Treaty permitted the United States to establish a base and conduct trade in Asia.

Now, nearly 100 years later, U.S. naval crewmen set up a table on the Missouri’s deck and laid out surrender documents. They displayed on a bulkhead the 31-star flag that Perry had sailed into Tokyo Bay a century earlier. High atop the big battleship’s flagstaff luffed the 48-star flag that had flown above the Capitol dome in Washington, D.C., on December 7, 1941.

At 9 a.m. sharp the Japanese delegates arrived – civilian officials in formal morning clothes, naval and military officers in dress uniform. Then General MacArthur and Admirals Nimitz and Halsey stepped on deck, dressed casually in open-collar khaki shirts. MacArthur’s brief speech noted his hope that “a better world shall emerge.” Then Japanese officials signed the surrender documents under the shadow of the Missouri’s 16-inch guns. After MacArthur and Nimitz signed for the Americans, both countries were officially at peace.

Of the men who had survived the Great War of 1914-18 and led the major powers into World War II, only one still stood on history’s stage by the end of 1945. FDR died of a massive intracerebral hemorrhage on April 12, 1945, while sitting for a portrait in Warm Springs, Georgia (at his Little White House). Hitler and Konoye Fumimaro died by their own hands (cyanide). Winston Churchill was shunted out of office in 1945 along with the conservatives by an electorate weary of sacrifice. (He also lost the 1950 election but returned to office in 1951.) Only Joseph Stalin remained, and he would die in 1953.

Following WWII, the United States and the Soviet Union established a vast Cold War in a fierce competition for global supremacy. The two sides never engaged in a physical war, but across nine U.S. presidents and six Soviet premiers, the two superpowers competed with each other. There was a decades-long arms race, building arsenals of nuclear and conventional weapons, and a space race that led to brilliant technological breakthroughs. They even vied for control of countries like Germany, dividing it into two parts. The city of Berlin was itself divided east and west, with a physical wall.

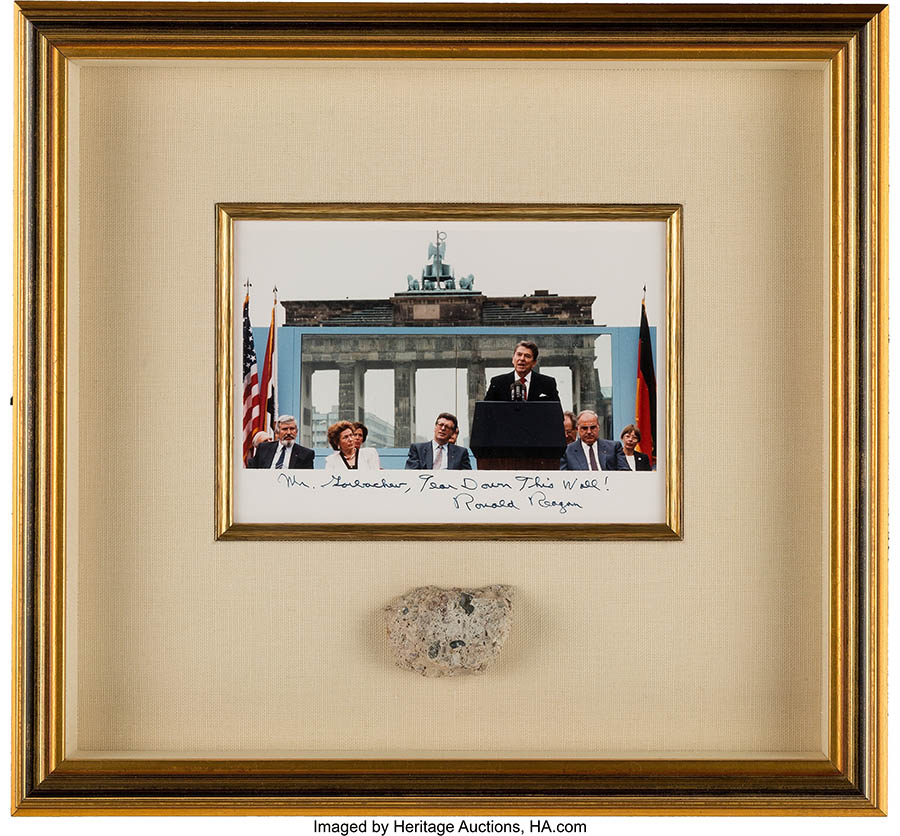

The Berlin Wall became the preeminent symbol of Cold War tensions and Communistic totalitarianism.

On June 12, 1987, President Ronald Reagan was in West Berlin to celebrate its 750th anniversary. He gave a speech in front of the Brandenburg Gate, advocating freedom and liberty. He then addressed Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev (who was not present) in words for the ages: “General Secretary Gorbachev…come here to this gate. Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”

Two years later the Soviet empire entered a state of terminal collapse. The USSR was no longer able to underwrite the Soviet bloc countries, and in 1989 country after country threw off the Communist rule. The Berlin Wall fell in November. In 1990 Soviet republics began breaking away, leaving only Russia. On Christmas Day 1999, the Soviet Union officially dissolved. The United States had won the Cold War.

In the intervening years the U.S. was actively involved in two other major wars: the Korean War (“the Forgotten War”) and the Vietnam War (the wrong war fought the wrong way). Now we are peering into the abyss of another European war as Russia systematically destroys Ukraine. Some experts believe the real threat to our security rests in China, which is patiently waiting on deck until its number is called. I’m brushing up on my rusty Mandarin just in case.

Maybe it was Toynbee who once said that countries don’t get defeated; they commit suicide.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].