By Jim O’Neal

When we lived in Central London in the 1990s, #10 Walton Street became a convenient place to host our American friends and family. We had plenty of room, one block from the world-famous Harrods department store, and the Walton Street restaurants were some of the finest in London. Our neighbor in #12 owned the superb Osteria San Lorenzo restaurant that Lady Diana claimed was her favorite, perhaps because it was three doors down from her exclusive couturier and go-to designer Bruce Oldfield. Michael Caine shopped at our Italian bakery, and Ringo Starr sightings were frequent.

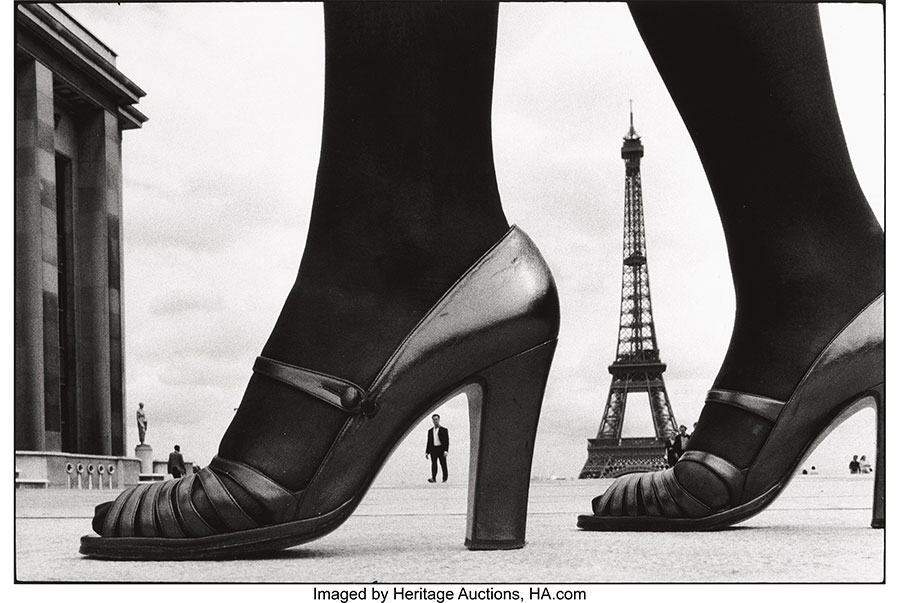

However, it soon became de rigueur to tack on a side trip to Paris via the new Eurostar high-speed trains that attained 180 mph under the English Channel that connected France and England. Once there, a pleasant lunch awaited visitors to the Eiffel Tower and the elegant Le Jules Verne, a one-star Michelin restaurant on the second level. It had a dedicated lift some 240 feet (thankfully).

The 360-degree view of Paris is wonderful at lunch and spectacular at night. “The City of Light” (La Ville Lumiere) derives from the city’s role in the Age of Enlightenment and the extensive use of gas lights on streets (56,000) and monuments. Located on the Champ de Mars, the Eiffel Tower was built as the entrance to the 1889 World’s Fair. It was named for the man who designed and built it. Gustave Eiffel had started working in a family vinegar factory owned by an uncle. When the business failed he switched to engineering, which proved to be quite rewarding.

He built bridges, viaducts and railway concourses that were awe-inspiring in addition to burnishing his reputation. It worked so well he won the commission to build the interior of the remarkable Statue of Liberty in 1884 that ended up being a gift from the French people to celebrate the founding of the young United States.

Sculptor Frederic Bartholdi generally gets credit for “Liberty Enlightening the World” and, of course, it was his design. However, without the ingenious interior engineering to hold it aloft, it was a hollow structure of beaten copper one-tenth of an inch thick. What Eiffel contributed was the ability of the 150-foot structure to withstand the wind, rain, snow, heat, cold and all the other physical weather assaults 24 hours, seven days a week year after year. These were all engineering challenges that Eiffel solved with a skeleton of trusses and springs that support the copper skin and is worn like a suit of clothes. It marked the invention of curtain wall construction, the most important building technique of the 20th century, but with little credit to the man who conceived it.

This new technique enabled the building of skyscrapers and the design of wings for airplanes. Eiffel’s contributions were about to be recognized for this breakthrough when he received the commission for his big project in Paris that we now call the Eiffel Tower. There were over 100 other proposals submitted, including a 900-foot-high guillotine, presumably as a tribute to France’s contribution to popularizing decapitation during the French Revolution.

Then, predictably, many scoffed at Eiffel’s design since it was so enormous and, on the surface, useless. It appeared to be an oil derrick but without any oil. Many people detested it, and unfortunately that included artists, architects and other high-profile notables. This highly influential group wrote a scathing petition on Feb. 14, 1887, denouncing “the grotesque mercenary invention of a lowly machine builder” and signed it “Artists against the Eiffel Tower.” Today we know just how totally wrong they were as 20 million people actually pay admission to tour what is probably the world’s most recognizable landmark-monument.

A similar controversy was roiling San Francisco in 1969, when we moved to San Jose, over the new Transamerica Pyramid. One critic called it “the most portentous and insidiously bad building in The City.” The San Francisco Chronicle’s architectural critic simply called it an abomination, while the Los Angeles Times called the spire gratuitous and compared it to a dunce cap. Angry mobs demonstrated by Mayor Alioto’s office to protest, but it was all in vain. The building was finished in 1972 and has gradually become a cherished, iconic symbol of the SFO skyline.

I wonder if the pyramids had to suffer through similar periods of rejection or ridicule? Retract that musing — I totally overlooked the presence of the Pharaohs. It is much easier to gain consensus when decision-making doesn’t involve others.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].