By Jim O’Neal

On Oct. 12, 2019, The New York Times ran an editorial titled “All the President’s Henchmen,” along with a cartoonish drawing depicting President Trump, Rudy Giuliani, Rick Perry and Pete Sessions. The article concluded, “The impeachment drama had taken on the feel of a telenovela crossed with a mob movie wrapped up in a true crime procedural and decorated with psychedelic TikTok clips. In a word: bananas. But with a cast of bumblers, grifters and self-promoters like those Mr. Trump seems to favor, one should expect nothing less.”

There was little doubt about the allusion to the 1976 Award-winning movie All the President’s Men. The film was almost exclusively based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning book of the same name. It had been authored by two obscure reporters for The Washington Post: Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward (now almost household names and prolific political writers).

The movie is one of my favorites, with Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman playing the two reporters. Jason Robards won an Oscar for his portrayal of Ben Bradlee, editor of the Post, and Alan J. Pakula was an Oscar nominee for Best Director. Although the movie primarily covers only the first seven months of what would become the Watergate scandal, the clever use of typesetting bookends the start and finish of the entire event, beginning with the Watergate break-in to Richard Nixon’s resignation several years later.

The actual Watergate affair started in 1972 when a security guard, 24-year-old Frank Willis, was on routine patrol in the basement of the Watergate complex. He found strips of tape across the latches leading to the underground parking garage. He was not overly alarmed. High-priced hotel rooms, prestigious offices and elegant condominium apartments within the Watergate development had been targets of burglars and thieves for several years. Along with three former Cabinet members, and various Republican leaders, the tenants included the Democratic National Committee (DNC). Its offices had been surreptitiously entered at least twice in just the last six months.

However, Willis simply assumed maintenance men had temporarily immobilized door latches as part of a routine repair. Professional burglars typically used less conspicuous wooden matches to keep the doors from closing and locking. The guard naively removed the tape, allowed the two doors to lock, and resumed his regular post in the lobby.

Then fate intervened and, acting strictly on what he called a “hunch,” he returned to take another look at the basement doors. The same latches had been taped again! Additionally, he discovered that two other doors on another level had been taped, despite being unobstructed only minutes before. “Someone was taping the doors faster than I was taking it off,” Willis said in an interview later. “I called the police!” His call was logged at 1:52 a.m. on Saturday, June 17.

First to reach the Watergate were members of the tactical squad of the Washington metropolitan force, who went directly to the top floor. More tape was found on a stairway door. They started working their way down and found tape on a sixth-floor office. With guns drawn, they entered the darkened offices of the Democratic National Committee. Five unarmed men were found crouched down and they surrendered quietly.

John Barrett, one of the plain-clothed officers who handcuffed the burglars, said: “They were very polite, but they would not talk.” The five men were arrested on burglary charges and led to the District of Columbia jail. They all gave false names to the booking officer, but after a routine fingerprint check, all five were identified:

- Bernard Barker, 55, a native of Cuba and president of a Miami real estate firm,

- James McCord, 55, president of a private security agency,

- Frank Sturgis, 48, ex-Castro Army, now at a Miami Salvage Company,

- Eugenio Martínez, 51, notary-real estate employee of Barker in Miami, and

- Virgilio Gonzalez, 45, a locksmith from Miami.

Four of the men had spent the night at the Watergate Hotel, which connected with the office building via an underground garage.

At the time of the arrests, police had seized all the equipment the men had. It was quite a haul: two 35mm cameras with close-up lens, 40 rolls of film, one roll of film for a Minox “spy” camera, and a high-intensity lamp. All were useful in copying documents. Additionally, there were three microphones and transmitters. Ceiling panels had been removed to allow access to an adjacent office belonging to DNC Chairman Larry O’Brien. In addition to lock-picks and burglary tools, there were two walkie-talkies and a few thousand dollars in $100 bills with consecutive serial numbers.

The White House was quick to deny that any of the men were working for them and Nixon Press Secretary Ron Ziegler famously shrugged it off as “a third-rate burglary attempt” and unworthy of comments. However, at their arraignment, Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward overheard one of the burglars (James McCord) whisper “CIA” when asked what kind of “retired government employee” he had been.

The finest journalists in the world could be forgiven for not realizing that those three little letters (CIA) would be the opening act of a scandalous political drama – unprecedented in American history. Bradlee would later write: “Some stories are hard to see because the clues are hidden or disguised. Other stories hit you in the face. Like Watergate, for instance. Five guys in business suits, speaking only Spanish, wearing dark glasses and surgical gloves, with crisp new hundred-dollar bills in their pockets, and carrying tear-gas fountain pens, flashlights, cameras and walkie-talkies, just after midnight in the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee. … You would have to be Richard Nixon himself to say this was not a story.”

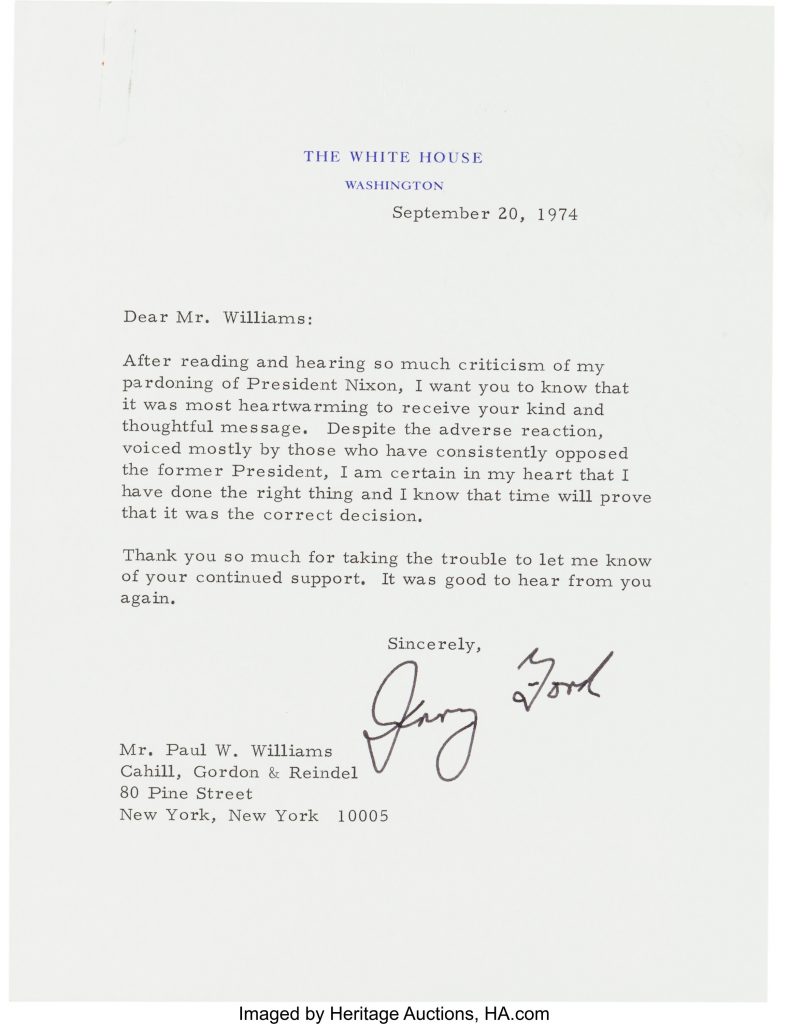

Actually, this is what Richard Nixon did finally say on Aug. 9, 1974, to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger:

Dear Mr. Secretary,

I hereby resign the office of President of the United States.

Sincerely,

Richard Nixon

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].