By Jim O’Neal

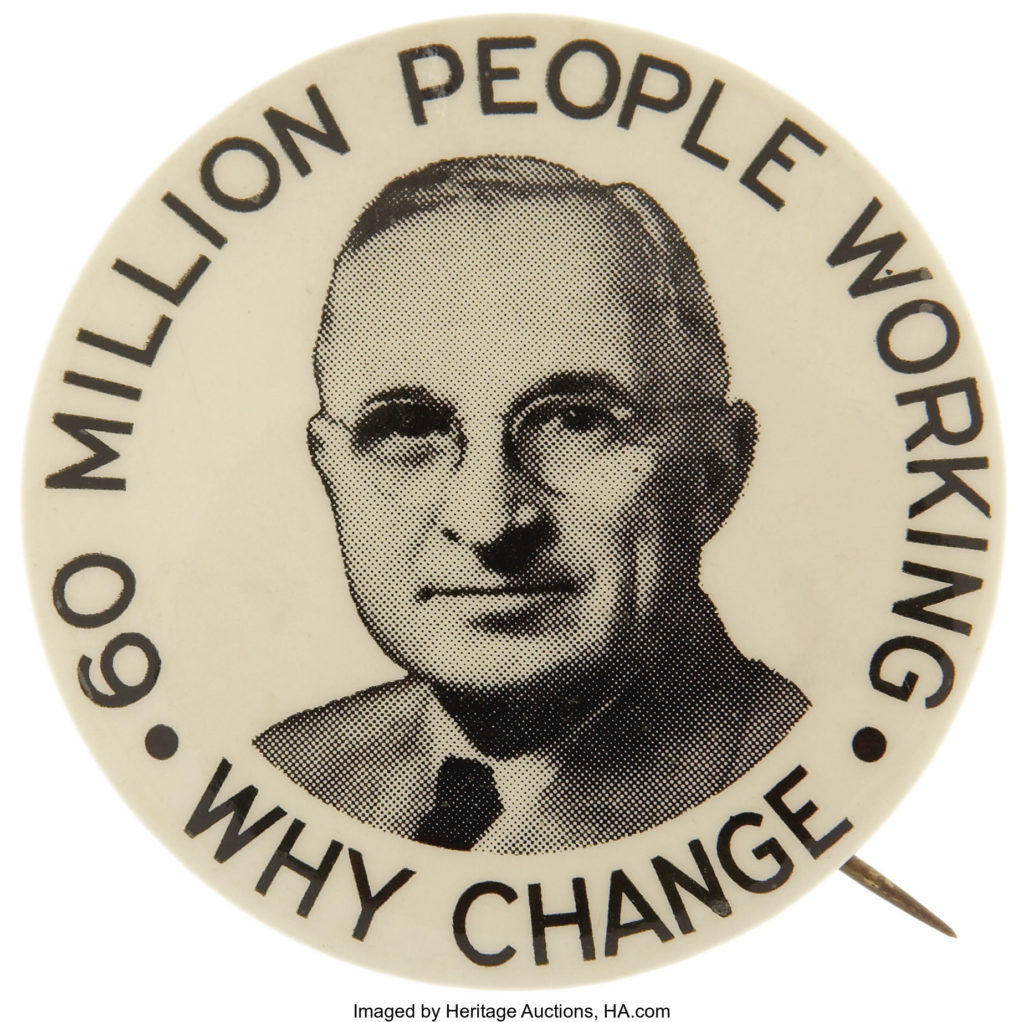

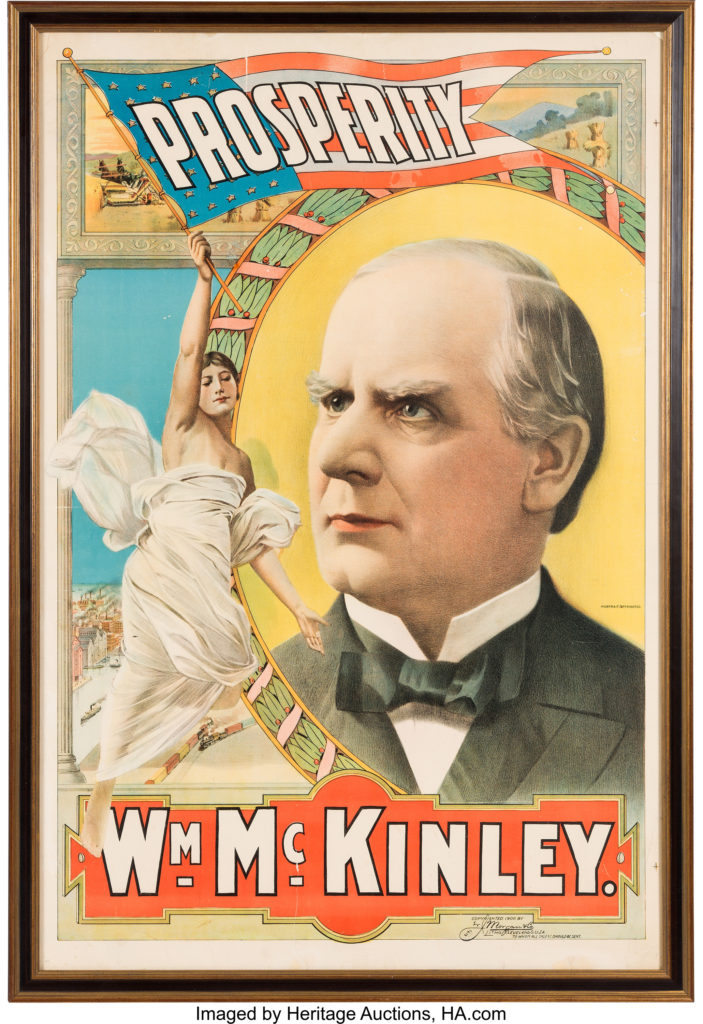

William McKinley was 54 years old at the time of his first inauguration in 1897. The Republicans had selected him as their nominee at the St. Louis convention on the first ballot on June 16, 1896. He had spent several years as an effective congressional representative and more recently the 39th governor of Ohio. Importantly, he had the backing of a shrewd manager, Mark Hanna, and the promise of what turned out to be the largest campaign fund in history – $3.5 million – largely by describing the campaign as a crusade of the working man versus the rich, who had impoverished the poor by limiting the money supply.

In the 1896 election, he defeated a remarkable 36-year-old orator, William Jennings Bryan, perhaps the most talented public speaker who ever ran for any office. McKinley wisely decided he could not compete against Bryan in a national campaign filled with political speeches. He adopted a novel “front porch” campaign that resulted in trainloads of voters arriving at his home in Canton, Ohio.

Bryan would lose again to McKinley in 1900, ducked Teddy Roosevelt in 1904, and then lose a third time in 1908 against William Howard Taft. The three-time Democratic nominee did serve two years as secretary of state for Woodrow Wilson (1913-15) and then died five days after the end of the Scopes Monkey Trial in 1925.

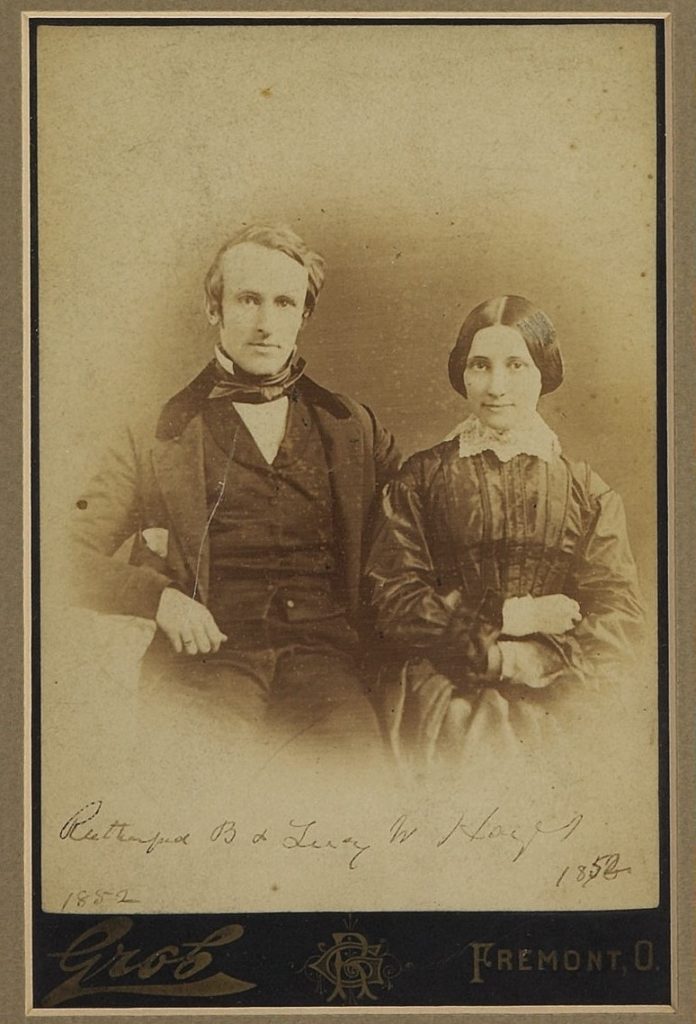

William and Ida McKinley followed Grover and Frances Cleveland into the White House after Cleveland’s non-consecutive terms as the 22nd and 24th president. Cleveland’s second term began with a disaster – the Panic of 1893 – when stock prices declined, 500 banks closed, 15,000 businesses failed and unemployment skyrocketed. This significant depression lasted all four years of his term in office and Cleveland, a Democrat, got most of the blame.

His excuse was the 1890 Sherman Silver Purchase Act, which required the Treasury to buy any silver offered using notes backed by silver or gold. An enormous over-production of silver by Western mines forced the Treasury to borrow $65 million in gold from J.P. Morgan and the Rothschild family in England. Since Cleveland had been unable to turn the economy around, it virtually ruined the Democratic Party and created the era of Republican domination from 1861 to 1933, with only Woodrow Wilson winning in 1912 when squabbling between Roosevelt and Taft split the vote three ways.

It’s common knowledge that McKinley was assassinated in 1901 after winning re-election in 1900, but there’s little attention paid to the time he spent in office beginning in 1897. 1898 got off to a wobbly start when his mother died, leading to a full 30 days of mourning that canceled an important diplomatic New Year’s celebration. Tensions between the United States and Spain over Cuba had electrified the diplomatic community and it was hoped that a White House reception would have provided a convenient venue to discuss strategic options.

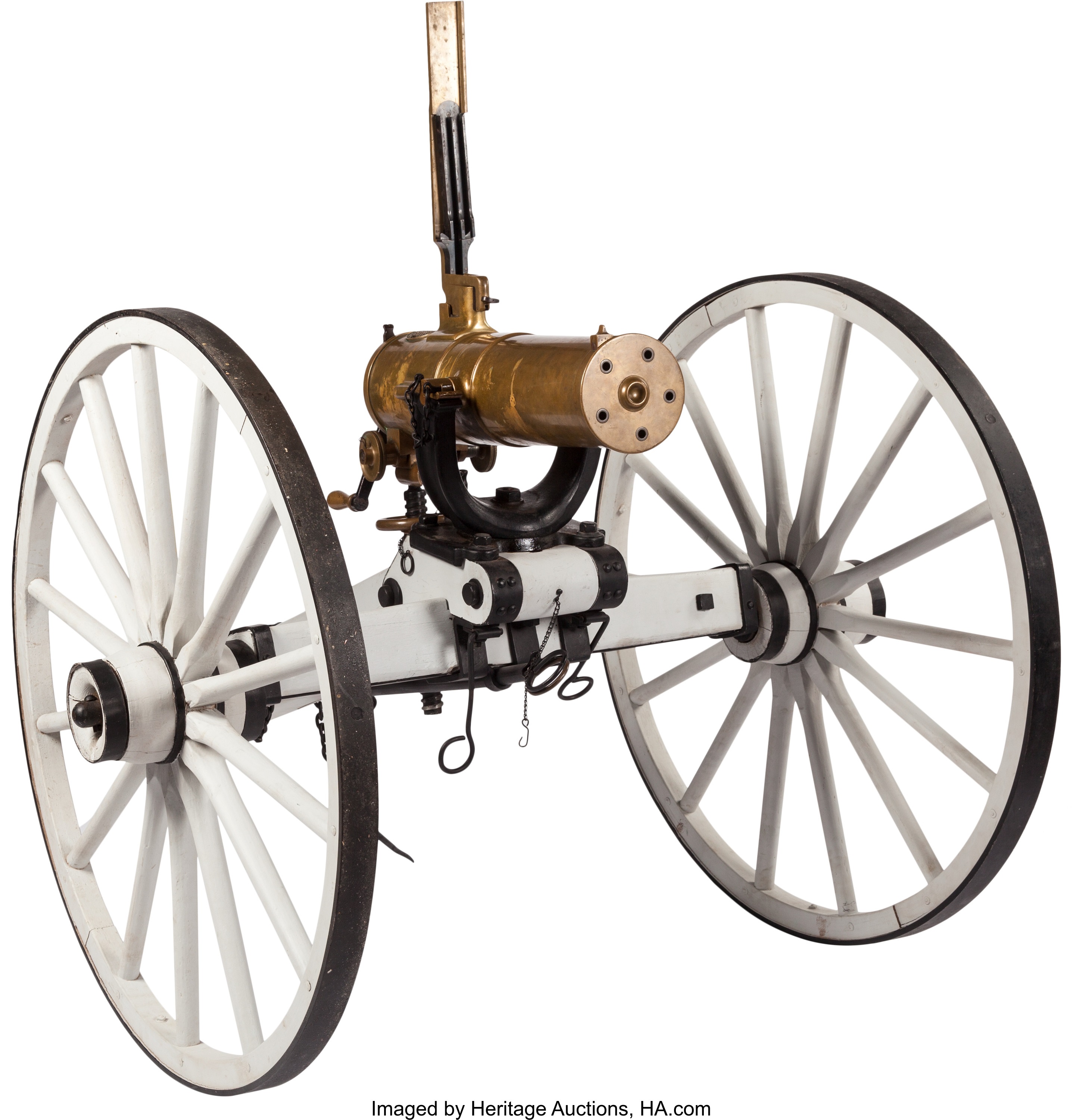

Spain had mistreated Cuba since Columbus discovered it in 1492 and in 1895, it suspended the constitutional rights of the Cuban people following numerous internal revolutions. Once again, the countryside raged with bloody guerilla warfare; 200,000 Spanish troops were busy suppressing the insurgents and cruelly governing the peasant population. American newspapers horrified the public with details that offended their sense of justice and prompted calls for U.S. intervention. Talk of war with Spain was in the air again.

On Feb. 9, two days before a reception to honor the U.S. Army and Navy, the New York Journal published a front-page article revealing the details of a Spanish diplomat denouncing McKinley as a weakling, “a mere bidder for the admiration of the crowd.” The same day, the Spanish minister in Washington retrieved his passport from the State Department and boarded a train to Canada.

A rapid series of events led to war with Spain, including $50 million that Congress placed at the disposal of the president to be used for defense of the country, with no conditions attached. McKinley was wary of war due to his experience in the Civil War, but he carefully discussed the issue with his Cabinet and key senators to ensure concurrence. This was the first significant step to war and ultimately the transformation of presidential power. On April 25, Congress formally declared war on Spain and the actual landing of forces took place on June 6, when 100 Marines went ashore at Guantanamo Bay.

McKinley’s skillful assumption of authority during the Spanish-American War subtly changed the presidency, as Professor Woodrow Wilson of Princeton University wrote: “The president of the United States is now … at the front of affairs as no president since Lincoln has been since the start of the 19th century.” Those who followed McKinley into the White House would develop and expand these new powers of the presidency … starting with his vice president and successor Theodore Roosevelt, who had eagerly participated in the war with Spain with his “Rough Riders at San Juan Hill.”

We see their fingerprints throughout the 20th century and even today as the concept of formal declarations of war has become murky. Urgency has gradually eroded the power enumerated to Congress and there is almost always “no time to wait for an impotent Congress to resolve their partisan differences.”

The Founding Fathers would be surprised at how far the pendulum has swung.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].