By Jim O’Neal

In 2014, Internet Trends reported that people uploaded 1.8 billion images every day, or 657 billion per year. One curious statistician calculated that every two minutes, more photos are snapped than the total number in existence 150 years ago. Since there is an obvious correlation between smartphones, populations and photos, if my math is correct, that translates to 1.2 trillion photos taken in 2017. However, all that I am certain of is that in the past three years I’ve personally taken approximately zero – despite having the newest iPhone around almost constantly. There must be a term for people like me, but I’m not familiar with it.

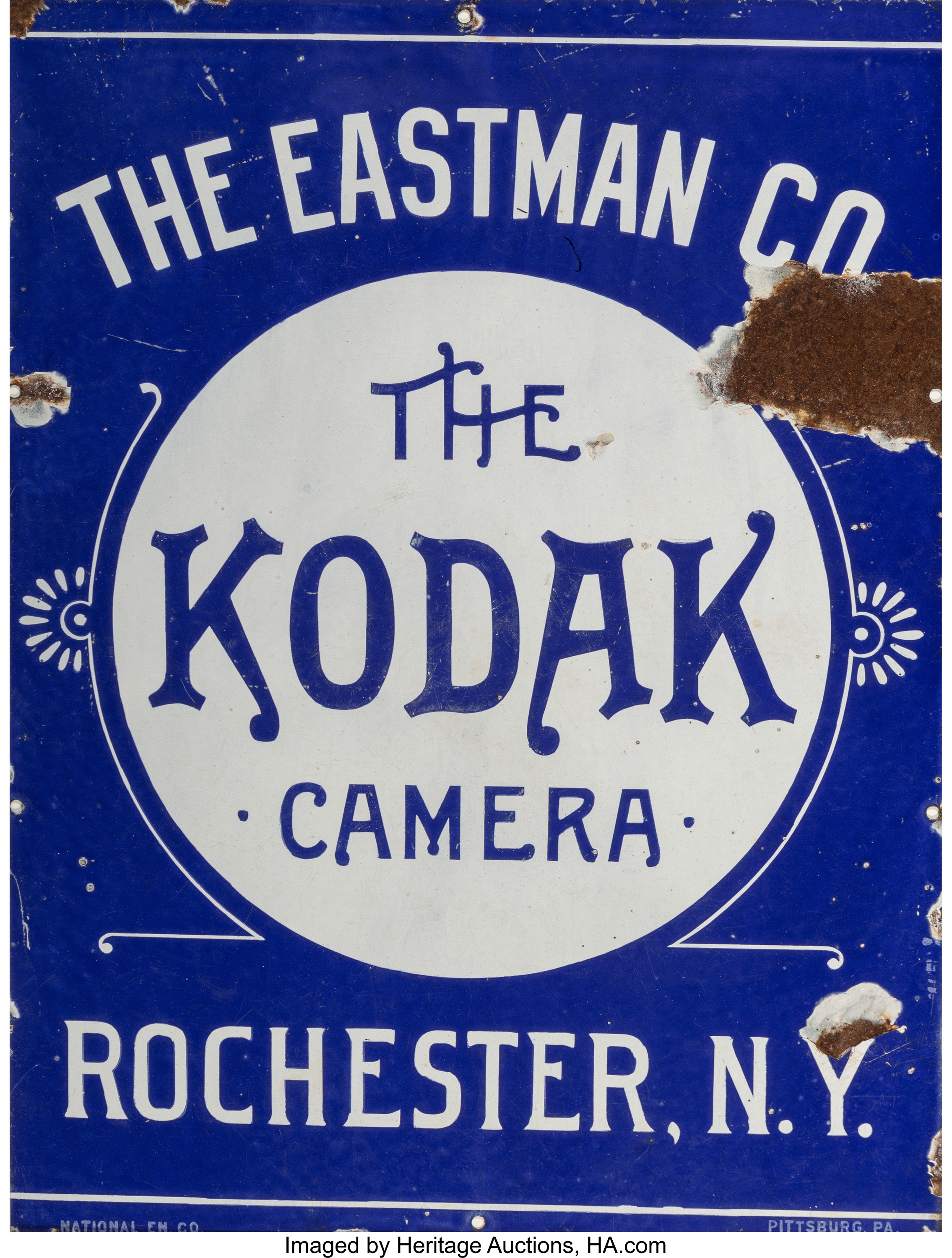

Anyway, the man who probably deserves most of the credit for this photographic phenomenon is George Eastman. In 1888, he invented the Kodak camera and a dry, transparent, flexible photographic film to use with the camera. Eastman was the founder of the once-famous Eastman Kodak Company and personally dreamed up a brilliant advertising slogan to induce average people to buy his new invention: “You push the button – we do the rest.”

Then in 1900, Eastman unveiled the first Brownie cameras and people quickly joined the Brownie Camera Club by the thousands. It was truly the birth of the snapshot and fostered the novel idea that every family (not just the rich) could actually create their own visual history for themselves and the generations that followed. Individual snapshots may have been relatively small from a mere size standpoint, but it was hugely democratic.

Those first Brownies used film that sold for 15 cents a roll, making photography financially feasible for virtually everyone in the country, no matter where they lived. More than a quarter of a million Brownies were sold in the first year and an astonishing 50 million by the early 1940s.

Eastman (1854-1932) was supremely confident about the positive effect of advertising to increase sales; and even more confident that a major effort to educate the public would be an essential element to make it a mass-market product. He wrote all the ads personally and championed the expansion of the brand internationally. One specific example was the word “Kodak” sparkling down from an electric sign on Trafalgar Square in central London.

When asked about the derivation of the word Kodak, Eastman would invariably say that “the letter K was my favorite. It’s a strong, incisive sort of letter. So it was simply a matter of trying out a great number of combinations of words that started and ended with K.” Add the distinctive yellow color that Eastman selected and Kodak became an instantly recognized brand all over the world.

The word that didn’t seem to fit the true impact of Eastman’s invention was “hobby.” His Brownie meant that aspiring photographers no longer had to be bothered by technical camera settings, precise focus or even film development. After exposing the film, the entire camera was then shipped back to Eastman’s factory. The film was developed, camera reloaded and mailed back to the customer along with the mounted prints. As early as 1896, the 100,000th Kodak camera was manufactured and the factory was churning out 400 miles of film and photography paper each month.

Eastman not only had powerful, creative ideas; he understood that he had to execute better than any of the inevitable competition. In time, Kodak had developed an impeccable reputation for affordable cameras and film. It was a formula that was replicated by Gillette (for razors and blades) and Sony (its Walkman provided a private, convenient concert in your ear any time of your choosing).

Yet as successful as Kodak became, there was someone else who would perceive our desire for even greater speed and instant gratification. (No, not Jeff Bezos.)

His name was Edwin Land (1909-1991) and in December 1943, he was on vacation with his family, walking around taking pictures (probably with a Kodak). Back in their room, his daughter posed a simple question: “But Daddy, why can’t I see the pictures now?” Instead of the standard reply … “Because you can’t” … Land started working on solving that problem. He recalled, “Within an hour, the camera, the film and the physical chemistry became so clear. I rushed to my patent attorney and described in great detail a dry camera which would give a picture immediately after exposure.”

Of course, he had conceptualized the Polaroid instant photographic process, which would own that category for decades. Their SX-70 instant color camera was an overnight success as we all responded to the massive TV advertising in which Sir Laurence Olivier sold us on the revolutionary idea of instant photography.

Alas, these two iconic photographic companies ended up in the largest patent suit, with Polaroid suing Kodak for infringing on 12 patents in 1976 and the litigation lasted until 1985, when Kodak was found guilty of infringing seven patents. The story has a sad ending since Kodak is now a shadow of its size and Polaroid ended up in bankruptcy, both victims of 20th century digital photography, which basically obsoleted everything else in sight.

But, think about all the memories that are stored in every house in America, just waiting for someone to take another look and spend time trying to figure out who all these people were and the stories about when they were taken. There is joy in all those cabinets.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].