By Jim O’Neal

While we lived in London, I was always fascinated by one common employee characteristic. Irrespective of the school – be it Eton, Oxford or the London School of Economics – every curriculum vitae (CV) included an explanation of a student’s foreign travels the year following graduation. Asia and Australia were the most popular; only rarely did it include the United States. After all the studying, cramming for exams and other typical activities on campus, they felt an overwhelming compulsion to just travel for as long as a year.

America was like that one time not too long ago. Novelist/journalist James Agee (A Death in the Family) wrote about it in Fortune magazine in 1934: Hunger for movement, he said, was “very probably the profoundest and most compelling of American racial hungers.” The road could help satisfy that hunger. Just put the hood ornament on the center line, the speedometer on 80 and let ’er rip. The urge was there before the car … long before … and invariably sent the country westward. As Huck Finn said: “But I reckon I got to light out for the territory ahead of the rest, because Aunt Sally she’s going to adopt me and sivilize me, and I can’t stand it. I been there before.”

The road was our nation’s ticket to ride and, more precisely, to ride away on. Maybe it was away from who we were, but it was, for sure, away from where we were. To where? Who knew? How about just a fresh start? We could put it all behind us as fast as the car could go.

Novelist/playwright William Saroyan, who liked getting behind the wheel of his Buick, wrote about his desire to hit the road: “It isn’t simply driving at night, it’s going on … to find out what’s out there now, not so much along the highway, in the terrain, under the sky, but in the interior of the driver himself.” Romance with the road was all about get up and go. Wherever you want to go, whenever you want to leave. There were no schedules and no reservations. Time of arrival? Whenever.

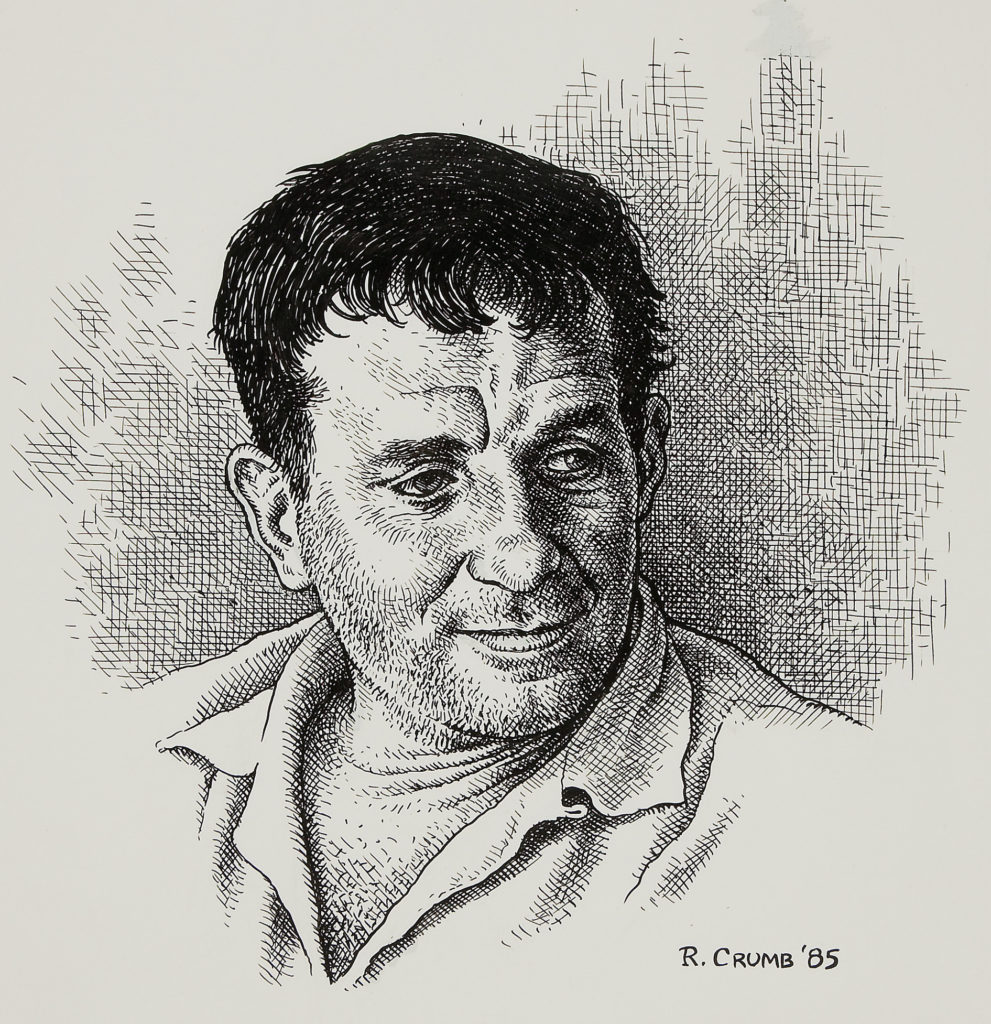

Lolita’s Humbert Humbert chose to hit the road to find his interior. Humbert’s creator, the Russian lepidopterist/novelist Vladimir Nabokov, spent two summers on America’s highways, chasing butterflies. A great year for the road was 1957. It was the year painter Edward Hopper gave us his classic Western Motel, the stark symbol of mobility and restlessness. The year that Jack Kerouac, out of the grim mill town of Lowell, Mass., weighed in with his novel On the Road. The road was Kerouac’s characters’ means of escape like the Mississippi was for Huck and Jim. On the Road captured the energy of trying to satisfy that hunger for movement.

The true north of the road was west. The West owned those lonesome, inexhaustible roads with few-and-far between motels designed so that cars could be parked about 20 feet from the beds. There was a lot of nowhere for these roads to cover. Distance was measured by hours (18 hours from Amarillo to Santa Monica), providing time to think. Playwright Sam Shepard used the road for writing and that may explain how he got the West so right.

John Steinbeck wrote that our “Mother Road” was Route 66. The Okies (including my whole family) called it their highway to heaven because it got us to California. We didn’t pick fruit like the Joads in The Grapes of Wrath. We bought real estate in Southern California that had its own fruit trees. I picked peaches and apricots off our three acres and I sold them in front of our house for 50 cents and $1 a lug. One uncle was a carpenter and he bought an entire block, built two houses, sold one for a tidy profit and lived in the other with a semi-alcoholic aunt.

My mother’s three brothers all found great jobs building airplanes and my father bought Pacific Cold Storage in Central Los Angeles (after he divorced my mother). I had two paper routes that netted me $60 a month after expenses (bicycle tires and rubber bands). I could also play night league softball in Huntington Park (we lived in Downey, home of the first Taco Bell 25 years later), and one-on-one basketball every spare minute.

My friends and I lived vicariously through TV shows like Route 66 with Martin Milner and George Maharis playing drifters in a Corvette – the only fictional series that shot all over North America – with their stories of working in shipbuilding, oilrigs and shrimping from Chicago to Los Angeles. (Corvette sales doubled). This was followed by Michael Parks in Then Came Bronson and the classic Easy Rider with Peter Fonda, Jack Nicholson and Dennis Hopper.

We had scratched our itch and found gold fast (sunshine, beaches, long-legged tan girls), but it was still fun watching others make their way west.

I wonder if space travel is what itches Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos?

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].