By Jim O’Neal

The Senate Judiciary Committee began hearings this week to consider the nomination of Judge Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court in their “advise and consent” role to the president of the United States. Once considered a formality in the justice system, it has devolved into a high-stakes political process and is a vivid example of how partisanship has divided governance, especially in the Senate.

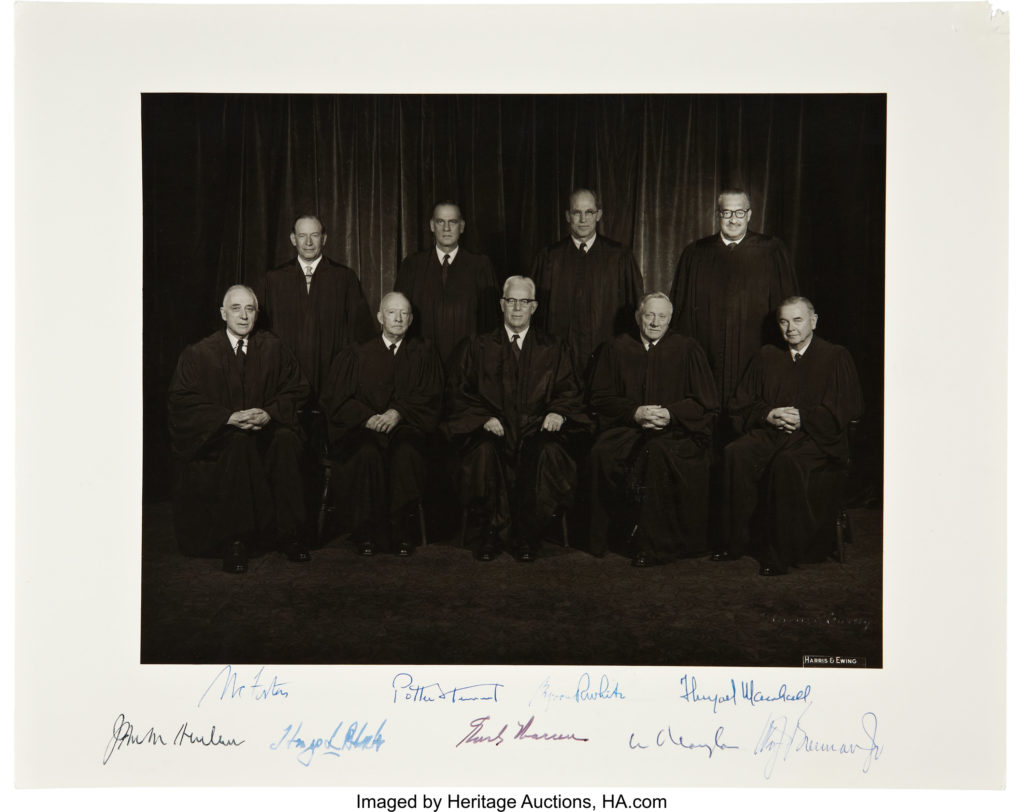

Fifty years ago, President Nixon provided a preview of politics gone awry as he attempted to reshape the Supreme Court to fit his vision of a judiciary. His problems actually started during the final year of Lyndon Johnson’s presidency. On June 26, 1968, LBJ announced that Chief Justice Earl Warren intended to resign the seat he had held since 1953. He also said that he intended to nominate Associate Justice Abe Fortas as his successor.

For the next three months, the Senate engaged in an acrimonious debate over the Fortas nomination. Finally, Justice Fortas asked the president to withdraw his nomination to stop the bitter partisan wrangling. Chief Justice Warren, who had been a keen observer of the Senate’s squabbling, decided to end the controversy in a different way. He withdrew his resignation and in a moment of pique said, “Since they won’t take Abe, they will have me!” True to his promise, Warren served another full term until May 1969.

By then, there was another new president – Richard Nixon – and he picked Warren Burger to be Warren’s replacement. Burger was a 61-year-old judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals with impeccable Republican credentials, just as candidate Nixon had promised during the 1968 presidential election campaign. As expected, Burger’s confirmation was speedy and decisive … 74-3.

Jubilant over his first nomination confirmation to the court, Nixon had also received a surprise bonus earlier in 1969. In May, Justice Fortas had decided to resign his seat on the court. In addition to the bitter debate the prior year, the intense scrutiny of his record had uncovered a dubious relationship with Louis Wolfson, a Wall Street financier sent to prison for securities violations. To avoid another Senate imbroglio over some shady financial dealings, Fortas decided to resign. In stepping down, Fortas became the first Supreme Court justice to resign under threat of impeachment.

So President Nixon had a second opportunity to add a justice. After repeating his criteria for Supreme Court nominees, Nixon chose Judge Clement Haynsworth Jr. of the U.S. Court of Appeals, Fourth Circuit, to replace Fortas. Attorney General John Mitchell had encouraged the nomination since Haynsworth was a Harvard Law alumnus and a Southern jurist with conservative judicial views. He seemed like an ideal candidate since Nixon had a plan to gradually reshape the court.

However, to the president’s anger and embarrassment, Judiciary Committee hearings exposed clear evidence of financial and conflict-of-interest improprieties. There were no actual legal implications, but how could the Senate force Fortas to resign and then essentially just overlook basically the same issues now? Finally, the Judiciary Committee approved Haynsworth 10-7, but on Nov. 21, 1969, the full Senate rejected the nomination 55-45. A livid Nixon blamed anti-Southern, anti-conservative partisans for the defeat.

The president – perhaps in a vengeful mood – quickly countered by nominating Judge G. Harold Carswell of Florida, a little-known undistinguished ex-U.S. District Court judge with only six months experience on the Court of Appeals. The Senate was clearly now hoping to approve him until suspicious reporters discovered a statement in a speech he had made to the American Legion 20-plus years before in 1948: “I yield to no man as a fellow candidate or as a citizen in the firm, vigorous belief in the principles of White Supremacy and I shall always be so governed!”

Oops.

Even allowing for his youth and other small acts of racial bias, the worst was yet to come. It turned out that he was a lousy judge with a poor grasp of the law. His floor manager, U.S. Senator Roman Hruska, a Nebraska Republican, then made a fumbling inept attempt to convert Carswell’s mediocrity into an asset. “Even if he is mediocre, there are lots of mediocre judges, people and lawyers. They are entitled to a little representation aren’t they, and a little chance?” This astonishing assertion was then compounded when it was seconded by Senator Russell Long, a Democrat from Louisiana! When the confirmation vote was taken on April 9, 1970, Judge Carswell’s nomination was defeated 51-45.

A bitter President Nixon, with two nominees rejected in less than six months, continued to blame it on sectional prejudice and philosophical hypocrisy. So he turned to the North and selected Judge Harry Blackmun, a close friend of Chief Justice Burger who urged his nomination. Bingo … he was easily confirmed by a vote of 94-0. At long last, the vacant seat of Abe Fortas was filled.

There would be no further vacancies for 15 months, but in September 1971, justices Hugo Black and John Harlan announced they were terminally ill and compelled to resign from the court. Nixon was finally able to develop a strategy to replace these two distinguished jurors, but it was only after a complicated and convoluted process. It would ultimately take Nixon eight tries to fill four seats, and the process has only become more difficult.

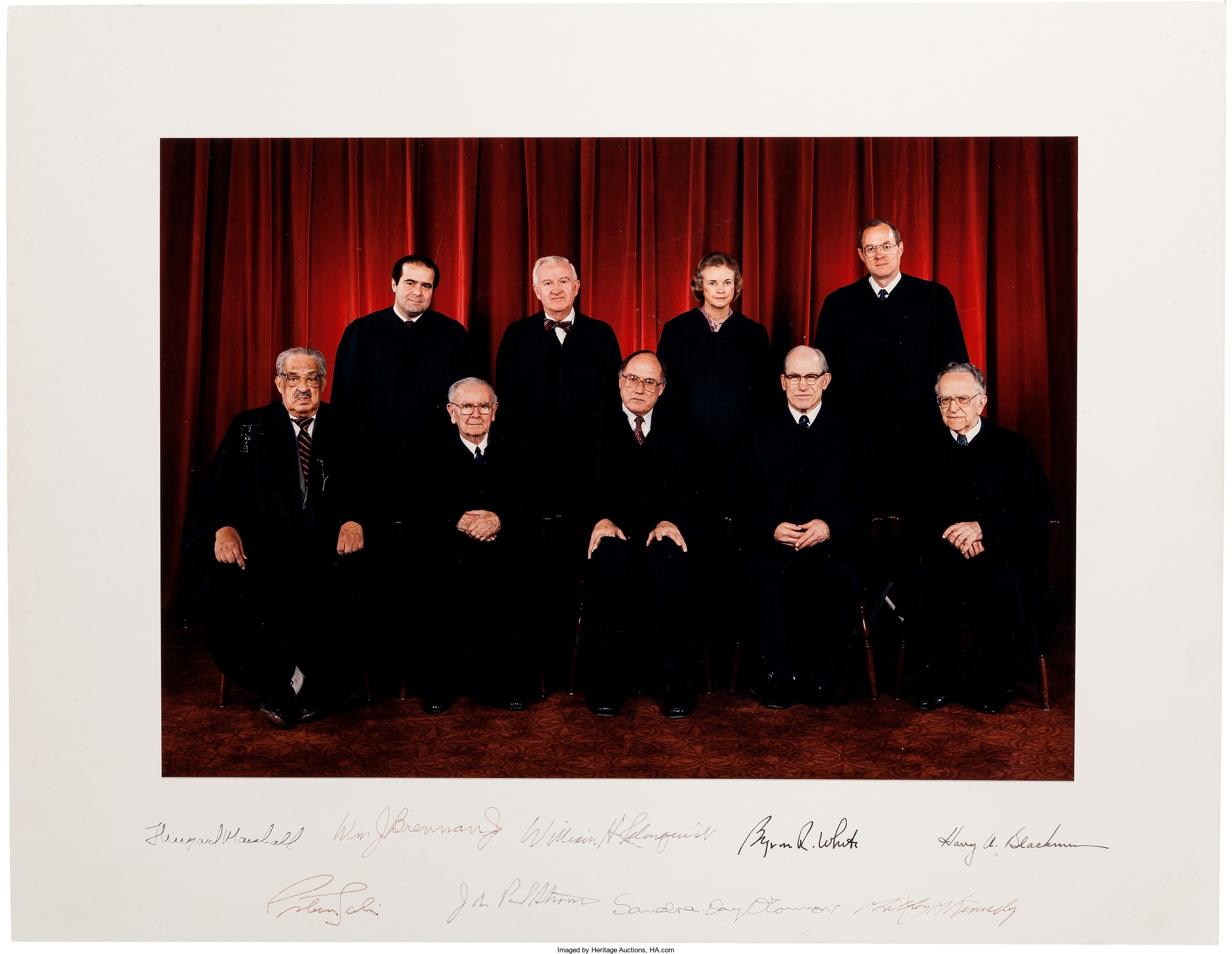

Before Judge Kavanaugh is able to join the court, as is widely predicted, expect the opposing party to throw up every possible roadblock they have in their bag of tricks. This process is now strictly political and dependent on partisan voting advantages. The next big event will probably involve Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a 25-year court member (1993) and only the second woman on the court after Sandra Day O’Connor. At age 85, you can be sure that Democrats are wishing her good health until they regain control of the Oval Office and the Senate. If not, stay tuned for the Battle of the Century!

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].