By Jim O’Neal

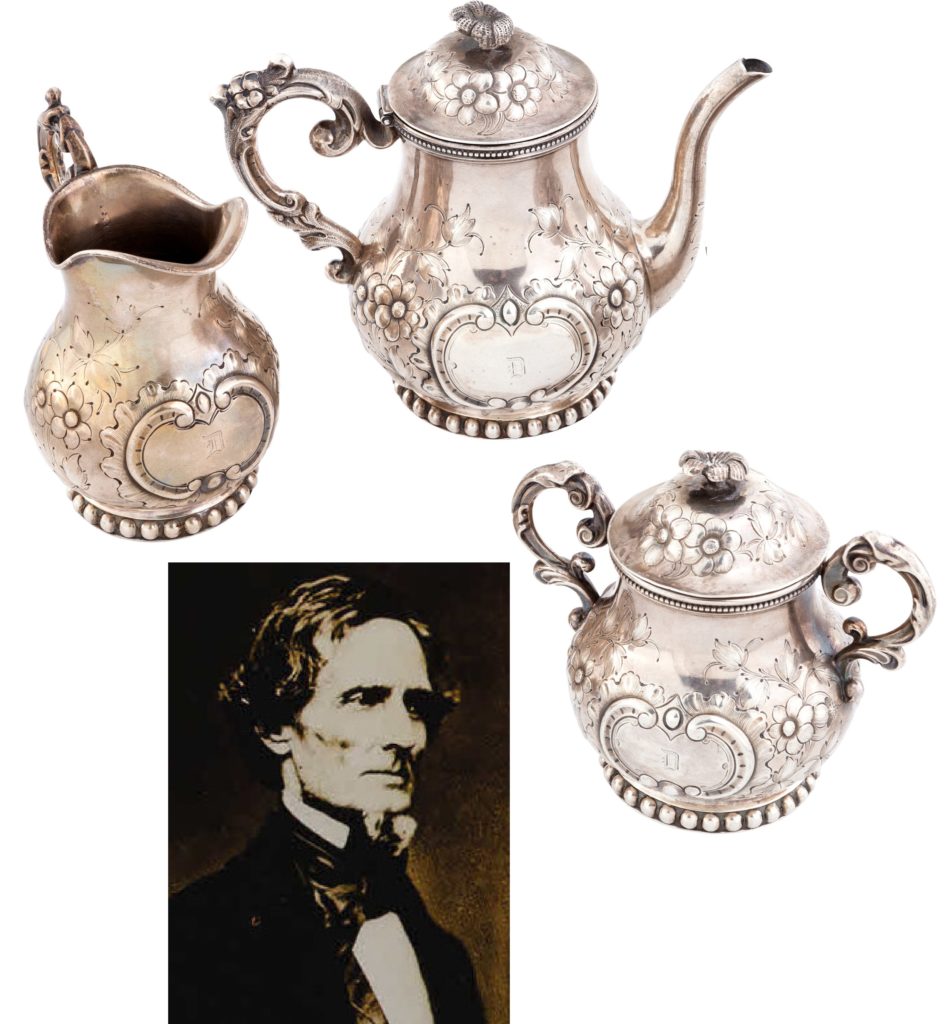

Newly elected President Franklin Pierce quickly selected his Cabinet and strategically picked a Southern Senator, Jefferson Davis of Mississippi, to be his Secretary of War in 1853. Davis would become president as well, as the first and only president of the Confederate States of America (1861-65).

Jeff Davis, like so many others in the South, did not support the secessionist movement, since he was convinced the North would not allow this to occur peacefully. However, he was also convinced that each state was sovereign and had an unquestioned right to secede. When war finally came, loyalty to state was an easy choice to make, irrespective of personal views on slavery.

President Davis had an extensive military career and his four years as Secretary of War made him fully aware of the North’s vastly superior military and industrial power. Further, there were 21 million people in the North (mostly white), a 2-to-1 advantage over the South, which had several million slaves. Nevertheless, on April 29, 1861, Davis requested an Army of 100,000 volunteers, knowing full well it would be difficult to equip and arm them on a sustainable basis.

Another man familiar with this significant issue was Colonel Josiah Gorgas, head of the Confederate Ordnance Bureau. Gorgas had three stark sources of supply for the Confederate armed forces: inventory (on hand), home production, and foreign imports. By using arms seized from federal arsenals, Gorgas had (barely) enough weapons to outfit the initial 100,000 forces called out by President Davis. Then he turned his full attention to the future.

Unlike others in the South, Gorgas was savvy enough to know that the war would not be over quickly and realized his meager on-hand stocks of munitions would soon disappear. Given enough time, he planned to establish munitions plants that would make the new nation self-sustainable, but until then, “certain articles of prime necessity” would have to be imported from Europe. In April 1861, he dispatched Captain Caleb Huse to Great Britain to set up a purchasing arrangement to obtain foreign supplies. Only two things went wrong. First, no local munitions were ever produced and no supply lines from Europe were set up because the funding strategy failed due to “King Cotton.”

King Cotton was a political and economic theory based on the coercive power of Southern cotton. The British textile industry imported 80 percent of the South’s cotton. Deny them this supply and the severe impact on the British economy would force them to intervene in the war to help the South. The second tenet was that Northern textile mills were reliant on Southern cotton and starving them would disrupt the Northern economy as well.

Then the South curiously imposed an embargo on cotton shipments in the summer of 1861 and, although designed to bring the British into the war, really only deprived the European group of the funds to buy imported supplies.

The obvious question is how did this small group of cotton farmers … with limited supplies and munitions and a failed strategy to obtain more … fight a war against an armed group backed by an industrial powerhouse, and manage to last four years while inflicting great losses and sustaining even greater losses of lives and property?

My simplistic answer:

- President Lincoln and his generals (especially George McClellan) were not focused on the total destruction of the enemy (hopeful of coaxing them back into the Union).

- They were interested in winning battles rather than controlling territory.

- They avoided destroying infrastructure (until William Tecumseh Sherman demonstrated its benefits).

- The South was fighting for its future. I see similarities to both Vietnam and Afghanistan … people who would never surrender and, as the Taliban explained, “You have the watches. We have the time.”

Thank the Lord for generals Grant and Sherman.

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].