By Jim O’Neal

In 1976, while planning a new Frito-Lay plant for Charlotte, N.C., a small group of us made a trip to Winston-Salem to visit R.J. Reynolds Tobacco. They had spent $1B on a computer-integrated manufacturing plant (C.I.M.) that was recognized as the largest and most modern cigarette plant in the world. We were interested in the latest automation technologies available for possible application in our new plant.

My two most vivid memories include the pervasive odor outside the plant that I (correctly) identified as menthol. This was not too tough since the plant was the major producer of Salem brand cigarettes (I assumed the rest were Winstons, given the town we were in). Second was that every single manager we met was a heavy smoker, with the biggest clue being the distinctive deep-yellow stain between their index and middle fingers. It was like being in a 1940s Bette Davis movie.

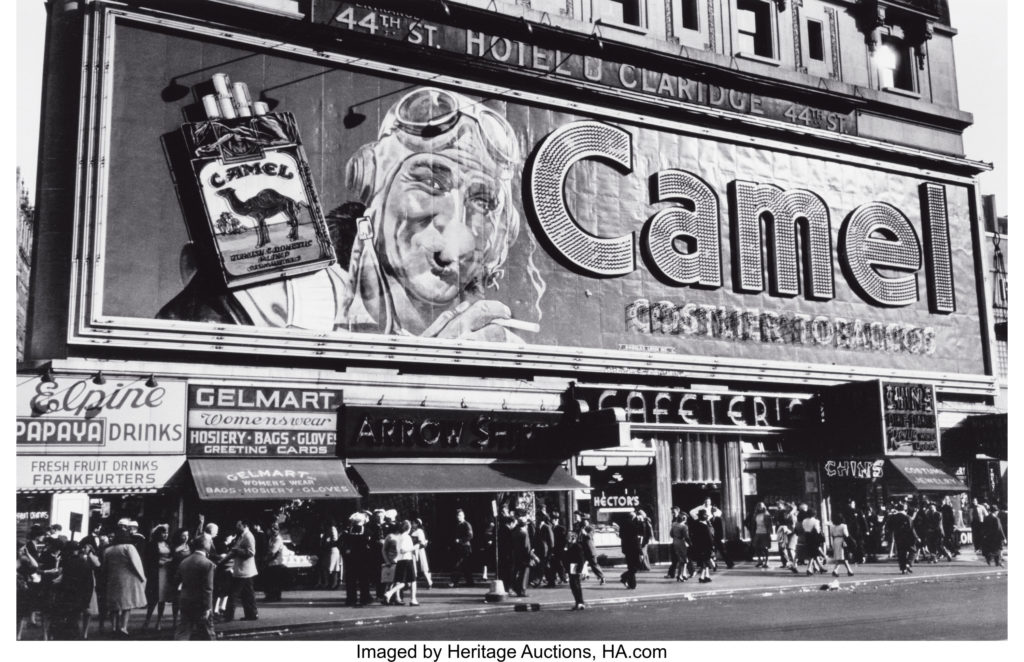

We finished up with an enjoyable dinner with David P. Reynolds, chairman emeritus of Reynolds Metals, whom I had known since my days involving aluminum foil and beer cans. He amused the group by telling old company stories, including “Lucky Strike Green Goes to War.” It seems that in 1942, they wanted to change the package design by substituting white ink for the more familiar green. Both copper and chromium were expensive ingredients in the green ink, so it simply “went to war” (and never returned). There was another story involving Camel and Kaiser Wilhelm (the original name favored for the cigarette that debuted in 1913). I don’t remember the details, but the moral of the story was … never name a product after a living person.

Later, I learned about Operation Berkshire, a secret 1976 agreement between all tobacco CEOs to form a collective defense against anti-smoking legislation (anywhere). Each pledged to never concede that smoking had any adverse health effects. We all recall the “Seven Dwarfs” testifying in April 1994 to the U.S. Congress (under oath) that nicotine was not addictive and smoking did not cause cancer. Movie tip: The Insider starring Russell Crowe ranks No. 23 on AFI’s list of the “100 Greatest Performances of All Time.” It tells the tobacco story of today brilliantly.

More than 400 years earlier, in 1604, King James I had written a scathing rebuke to the evils of tobacco in A Counterblaste to Tobacco. He was the son of Mary, Queen of Scots, and ascended to the English throne when Elizabeth I died childless. He wrote of tobacco as “lothsome to the eye, hatefull to the Nose, harmefull to the braine, [and] dangerous to the Lungs.” He equated tobacco with “a branche of the sinne of drunkenness, which is the roote of all sinned.”

Tobacco was late to arrive in England. Fifteenth-century European explorers had observed American Indians smoking it for medicinal and religious purposes. By the early 16th century, ships returning to Spain took back tobacco, touting its therapeutic qualities. The Iberian Peninsula eagerly adopted its use.

When English settlers arrived in Jamestown in 1607, they became the first Europeans on the North American mainland to cultivate tobacco. Spotting an opportunity in 1610, John Rolfe (of Pocahontas fame) shipped a cargo to England, but the naturally occurring plant in the Chesapeake region was considered too harsh and bitter. The following year, Rolfe obtained seeds of the milder Nicotiana tabacum from the Spanish West Indies and soon production was rapidly growing and spreading to Maryland. By the middle of the 18th century, Virginia and Maryland were shipping nearly 70 million pounds of tobacco to Britain.

Even as many Colonial leaders in America believed that smoking was evil and hazardous to health, it had little effect on the relentless spread of tobacco farming. By the eve of the Revolutionary War, tobacco was the leading cash crop produced by the Colonies. Exports to Britain rose to over 100 million pounds … 50 percent of all Colonial trade. Never was a marriage of soil and seed more bountiful.

But tobacco cultivation and manufacturing were extremely labor-intensive activities. Initially, white indentured servants were used to harvest the crop and inducements to come to America often came in the form of a formal “indentured servitude” agreement. Typically, in exchange for agreeing to work for seven years, the servant would receive his own land to farm. This system was preferred over slavery; losing a slave was seen as more costly than losing an indentured servant.

Then the economics started shifting as land became scarcer and slaves more plentiful due to King Charles II. He decided to create the Royal African Company of England and grant it a monopoly with exclusive rights to supply slaves to the Colonies. Then, with the explosion of cotton production, there was an enormous demand for more slaves.

A cynic might note that the formation of the United States was first led by men from Virginia and then governed by them. President Washington, followed by Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and, finally, James Monroe … four of the first five presidents … all from Virginia and all with slave plantations.

Throughout our history, there has been a lot of money made from tobacco. As the plant manager at that C.I.M. plant explained, “We ship about 800 rail cars filled with cigarettes every eight hours and they come back loaded with cash.”

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].