By Jim O’Neal

The Jamestown settlement in the Colony of Virginia is credited with being the first permanent English settlement in the Americas. The Colonists had sailed in a fleet of three ships: the Susan Constant, Discovery and Godspeed – under the command of Captain Christopher Newport (1561–1617) and arriving in 1607. They endured repeated failures and humiliations as a commercial entity.

King James (1566-1625) revoked the London Company’s charter in 1624 after a cumulative investment of 200,000 lb. sterling and over 100 additional shipments of supplies to keep them going. But it was a combination of an Indian massacre in 1622 and a seeming inability to develop a viable economy that prompted the king’s action. Their inability to protect the king’s people resulted in Virginia ceasing to be a commercial company and instead being governed as a mere Colony.

As early as the 15th century, European explorers had observed American Indians smoking tobacco, presumably for ceremonial or medicinal purposes. In the 16th century, ships returning to Spain brought back tobacco and it was soon adopted as a therapeutic cure-all throughout the entire Iberian Peninsula. Naturally, it spread to England after Sir Francis Drake (c.1540-1596) brought supplies of tobacco leaf and seeds for planting. By 1600, pipe smoking had become popular in upper-class London society.

Surprisingly, King James objected quite strenuously and published (perhaps) the very first treatise against tobacco in 1604: “A Counterblaste to Tobacco.” He questioned why honorable men would “imitate the barbarians and beastly manners of the wilde, godless and slavish Indians especially in so vile and stinking custome.” Much of the rest of the tirade/admonition, would fit very well with modern anti-smoking efforts still active in many parts of the world.

Refuting a view that tobacco was a magic cure for everything, he asked, “What greater absurdity can there be than to say that one cure shall exist for all divers and contrarious sorts of diseases?” He then went on to point to poisoning of the lungs and disruption in the function of organs. Finally, the treatise compared tobacco use with “a branch of the sin of drunkenness, which is the root of all sins!”

The Virginia Colony, by not being able to keep the king’s subjects safe from Indians and losing their charter, missed a chance to control the tobacco monopoly, which turned out to be America’s most valuable commodity in the 17th and 18th centuries.

When a young man named John Rolfe (1585-1622) planted seeds of a Spanish variety from the West Indies, “Never was a marriage of soil and seed more fruitful,” wrote Joseph Robert in his Story of Tobacco in America. Virginia soil along the James River (named for the anti-tobacco king) proved to be an enormous success. By the end of the 18th century, Virginia and Maryland were shipping 70 million tons of tobacco to England each year.

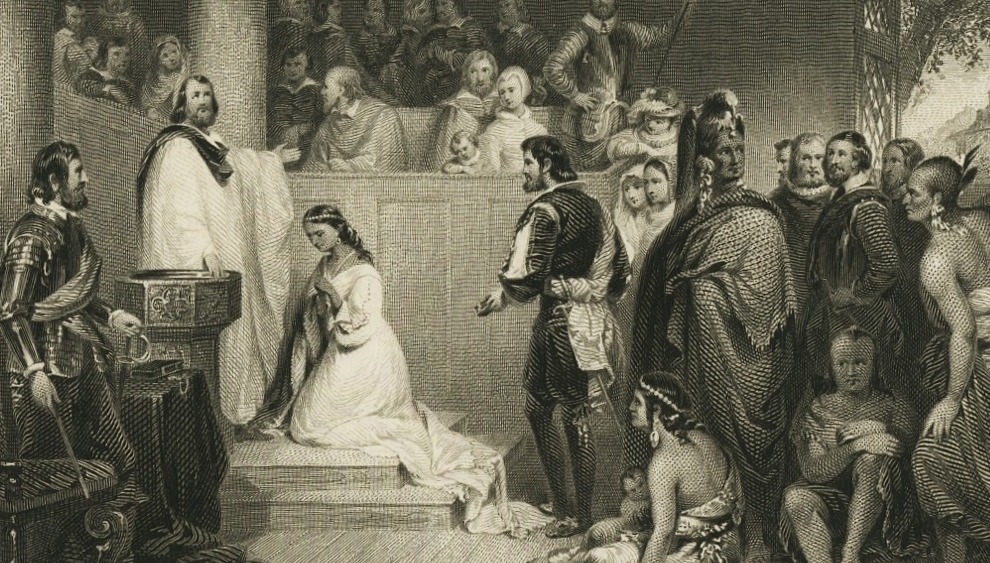

Rolfe, of course, would go on to marry Pocahontas (c.1596- 1617), the daughter of the influential Indian Chief Powhatan, in April 1614. She had been a captive of the Colonists during hostilities in 1613, converted to Christianity and baptized as Rebecca. The Rolfes soon traveled to London, where Rebecca was introduced as a “civilized savage,” all in a failed attempt to gain more investment in Jamestown. When the Rolfes set sail back to Jamestown, Rebecca became ill and died. Pocahontas had become a semi-celebrity in England and numerous places are named for her.

The Colonial focus on tobacco presented a risk to the “tillage of corn,” which was essential to basic food supplies needed to feed the people. The governor decreed that every man must plant two acres of corn before planting any tobacco. Then another consequential event occurred in 1619. A Dutch man-of-war sold the Company “20 and odd” Black slaves – the first slaves in what would become the American Colonies.

From these modest beginnings, there was a major shift in labor from White indentured servants to African slaves in the labor-intensive activities for tobacco cultivation, harvesting and curing. By 1860, 350,000 were cultivating tobacco – an exploitive crop that exhausted the soil and required constant cleaning of new land. Throughout the Colonial period, production of tobacco was centered in the Northern port cities, but the surplus slave labor, supply of raw material and manufacturing shifted to the South. By 1765, Virginia and Maryland tobacco combined to represent 80 percent of American exports.

Leading up to the American Revolution, South Carolina exported more than all the Northern Colonies combined and became a majority slave Colony. Of a population of 125,000, about 75,000 were slaves. Virginia had more Blacks than New York had Whites. On the eve of liberty, the majority of American exports were produced by slave labor.

Predictably, as the concentration of wealth grew, the men who controlled tobacco controlled Virginia politics. One generation into the 18th century, Virginia’s most esteemed citizens comprised a landed aristocracy – but much like the modern oil state that usually fails to develop other economic capability. However, a significant exception is that Virginia’s soil was fertile ground for fresh, new ideas on freedom and governance. This relatively small area supplied an abundance of intellectual foundations and some obvious contradictions to the coming American experiment.

We are still learning.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].