By Jim O’Neal

If our past is any guide to the future, I suspect that presidential politics will be a primary source of contention for several electoral cycles. The United States has produced some unusual presidential elections and the 2020 Biden vs. Trump race is not an isolated event that warrants exceptional anxiety.

A little history helps keep it in perspective.

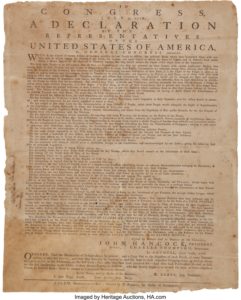

During the 1787 Constitutional Convention, there was a long debate over the method for selecting a president. Among the proposals was whether the chief executive should be chosen by a direct popular election, by the Congress, by state legislators or intermediate electors. Direct election was rejected primarily because of a concern that common citizens would probably lack sufficient knowledge of the character or qualifications of candidates that would enable intelligent choices. Candidates would be spread throughout the 13 colonies and campaigning was not a viable option due to travel difficulties.

Letting Congress decide was quickly rejected since it would jeopardize the principle of executive independence. Similarly, allowing state legislatures to choose was turned down because the president might feel indebted to some states and allow them to encroach on federal authority.

Unable to agree, on Aug. 31, the Convention appointed a “Committee of Eleven” to resolve it. On Sept. 4, a compromise was agreed with each state appointing Presidential Electors, who would meet in their states and cast votes for two persons. The votes would be taken to Congress to be counted, with the candidate receiving a majority elected the presidential candidate and the second highest vice president. Since there was no distinction between which vote was specifically designed by position, the 12th Amendment was ratified 1804 to distinguish individual votes between the two offices.

Now the conventional election of president and vice president is an indirect election in which (only) citizens, who are registered to vote in Washington, D.C., or one of the 50 states, cast ballots for members of the Electoral College. Those electors cast the direct votes and it requires at least 270 electoral votes to win. In 1960, the 23rd Amendment granted D.C. citizens the same rights as the states to vote for electors, but they can NEVER have more votes than the least populous state. To date, they have never had more than three electors. Also, they do not have any rights to vote for senators or amendments to the Constitution.

For more than 200 years, Americans have been electing presidents using the Electoral College, but despite its durability, it is one of the least admired political institutions. Thomas Jefferson called it “the most dangerous blot on our Constitution.” It’s been an easy target for abolishment or modernization and polls consistently report citizens would much prefer a simpler direct election. However, amendments require a 2/3 majority in both the House and Senate or a complicated state ratification convention with 3/4 approval. This process has never been attempted.

This outdated system has led to a number of anomalies at times. In 1836, the Whigs tried a novel approach by running different candidates in different parts of the country. William Henry Harrison ran in New England, Daniel Webster in Massachusetts and Hugh White of Tennessee in the South. By running local favorites, they hoped to subsequently combine on one candidate or force the election into the House. The scheme failed when Democrat Martin Van Buren captured the majority.

Another quirk of fate occurred in 1872 when Democratic nominee Horace Greeley died between the popular vote and the meeting of the electors. The Democrats were left without an agreed candidate. Forty-two voted for Governor Tom Hicks … 18 for Gratz Brown … two for Charles Jenkins and three Georgia electors cast their votes for the dead Greeley (Congress refused to accept them).

In 1912, President William Howard Taft and ex-President Theodore Roosevelt caused a split in the Republican Party that allowed Democrat Woodrow Wilson to become president. On Oct. 14, just before a major speech, a fanatic named John Shrank stepped up, shouted something about a third term and shot T.R. in the chest. Roosevelt yelled at the crowd to stand back and declared “I will make this speech or die. It is one thing or the other!” He went on to make a 90-minute speech before heading for the hospital. The bullet had lodged in the massive chest muscles instead of penetrating the lungs! Wilson won but Taft finished a weak third place.

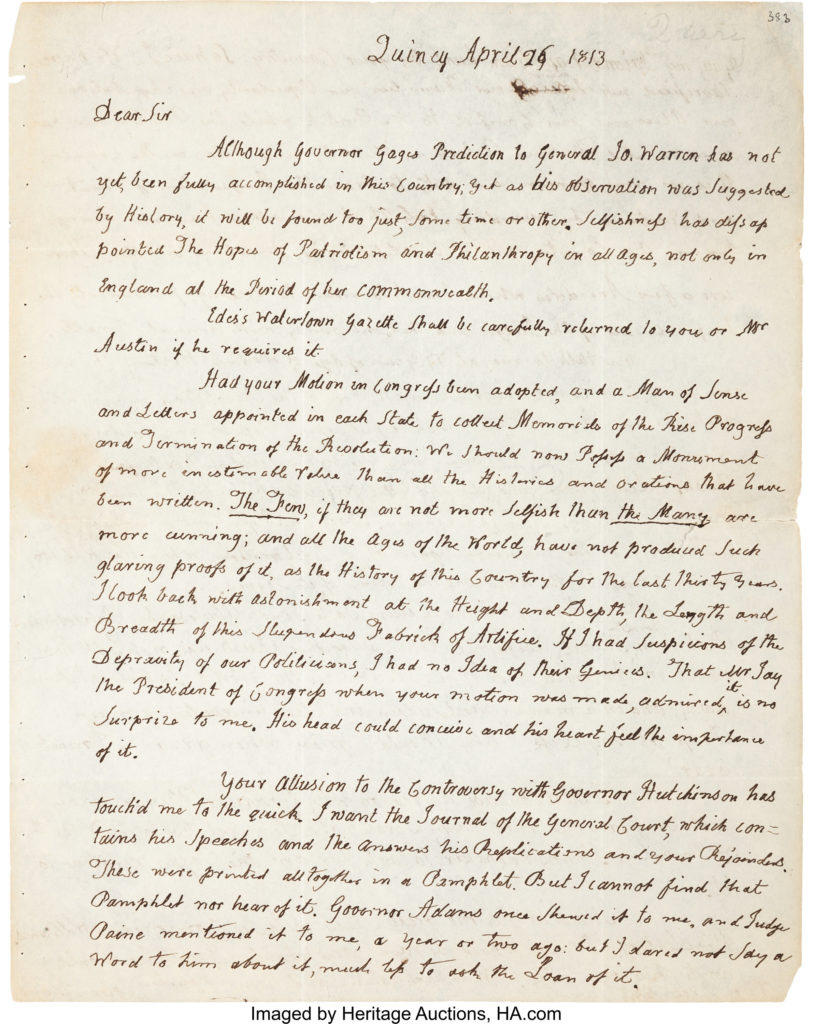

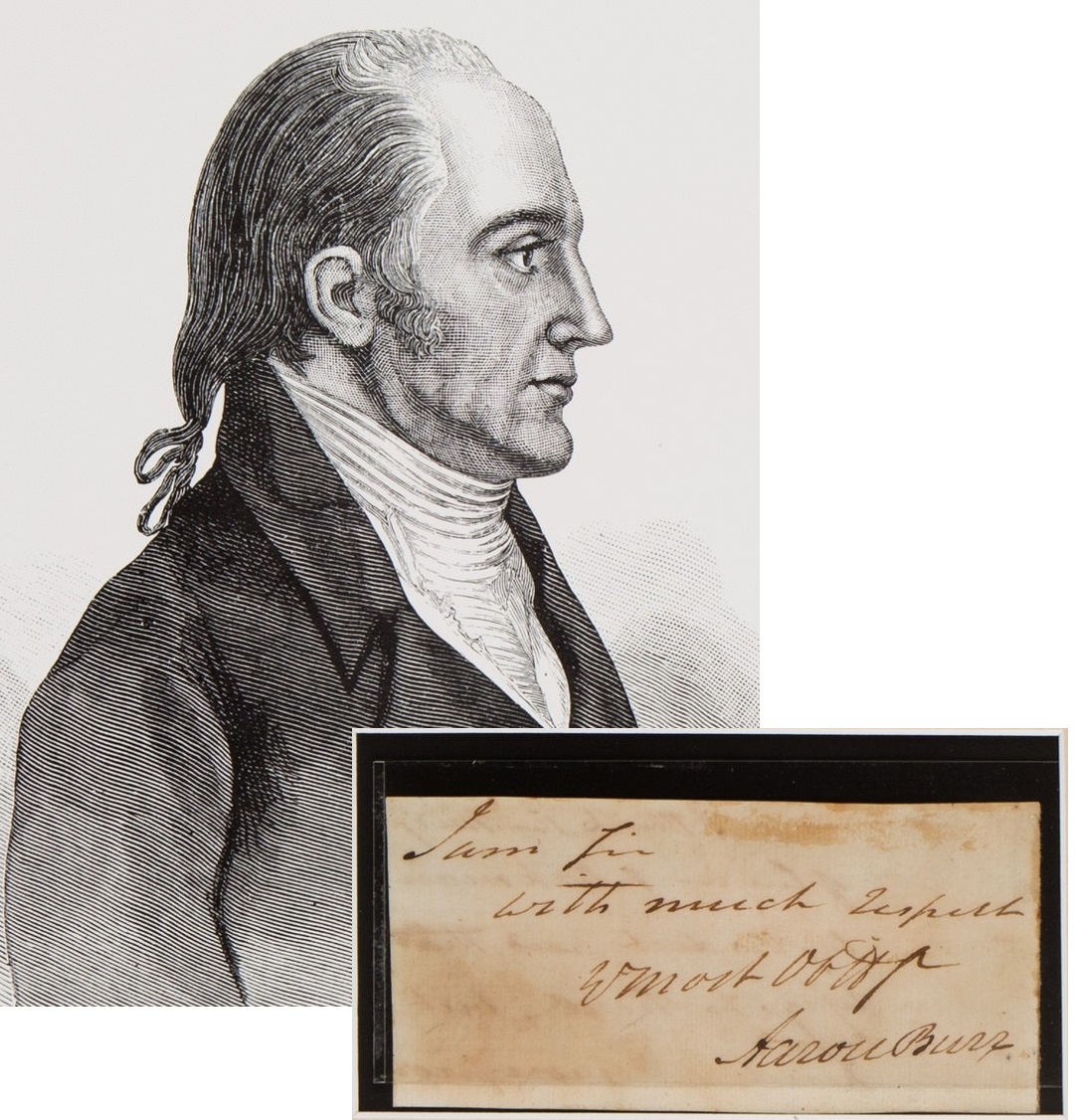

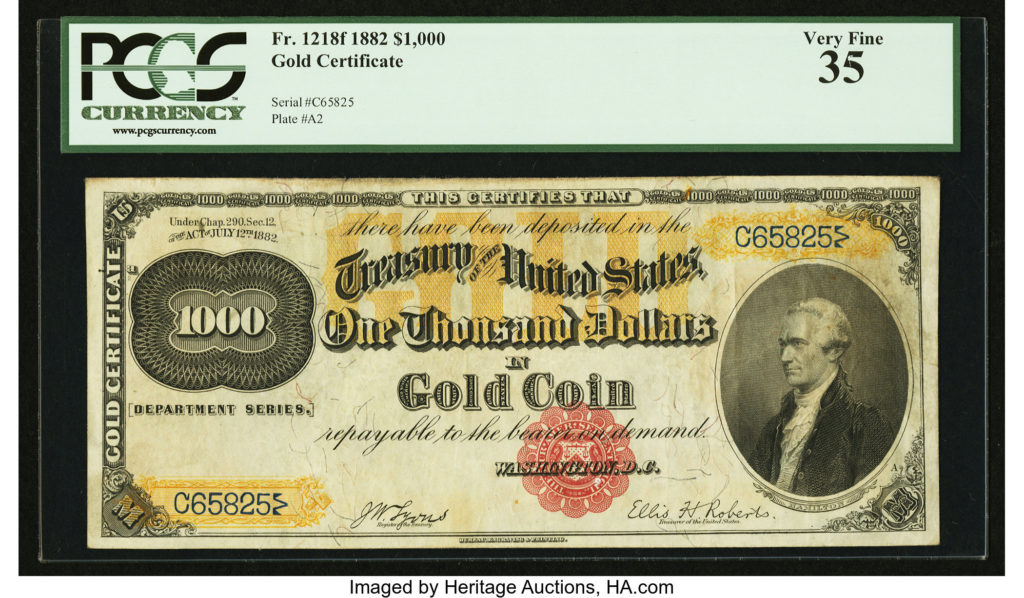

Lastly, compared to “the Revolution of 1800,” the 2020 election was mild and relatively free of widespread disorder. The 1800 campaign was so bitter that VP Aaron Burr ended up killing Alexander Hamilton in a duel and John Adams and Thomas Jefferson would not communicate with each other for 12 years.

Neither Abigail nor John Adams would attend the inauguration. Sound familiar?

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].