By Jim O’Neal

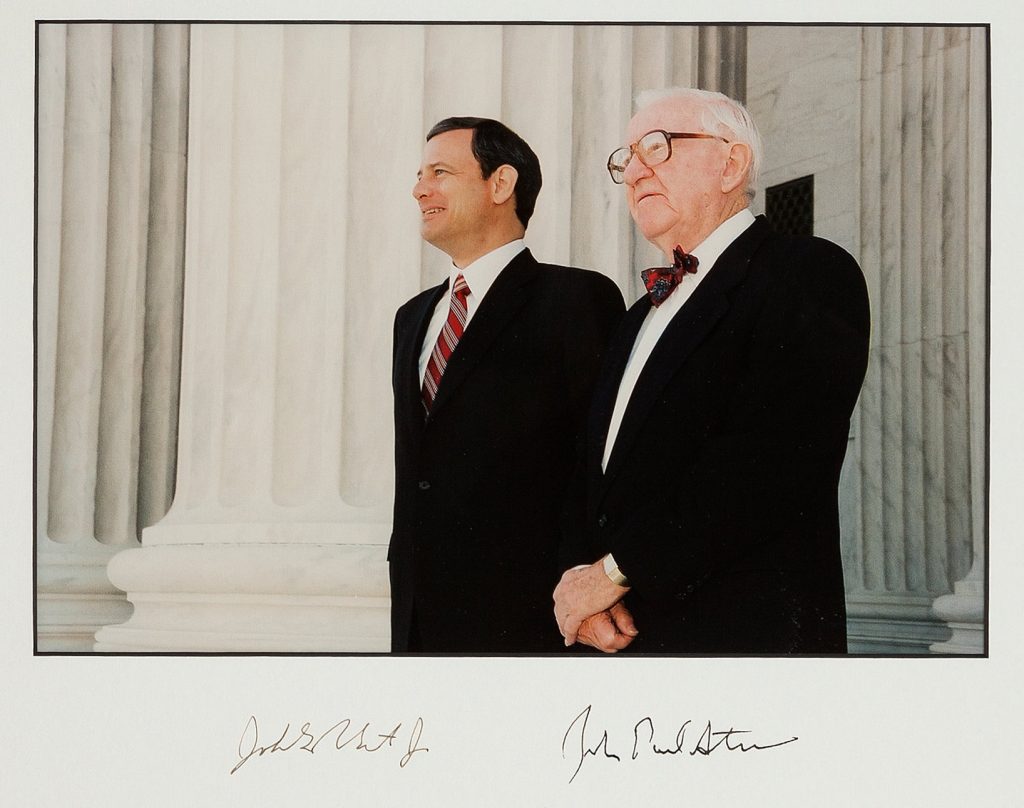

At noon on Sept. 12, 2005, I was glued to the TV to watch the start of the Senate Judiciary Committee. Chairman Arlen Specter gaveled the committee to order to consider the nomination of Judge John Glover Roberts Jr. as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Day one included Judge Roberts’ introduction of his family and friends in attendance, followed by four short speeches by prominent senators advocating for his confirmation. This abbreviated session was to accommodate the short attention spans of Roberts’ two young children. The meeting was adjourned for the day with the formal occasion to resume the following morning.

As an amateur connoisseur of great speeches and the courtroom drama that testimony in front of Congress can engender, I was impatient for the next day. I was not disappointed. Judge Roberts, dressed in a black suit and starched white shirt and tie (but without his customary gold cuff links) looked like he was out of central casting. He assumed his seat after the customary swearing-in ritual. However, what was strikingly different was the starkness. The table where he sat and made his opening statement was devoid of items. Not a single note, pen or even a glass of water. One man sitting all alone looking up at 18 senators (nearly half of them partisan enemies hoping to derail his career), while he looked totally relaxed, confident and alert.

Devoid of any speeches or even cue cards, he politely thanked several and transitioned to his Indiana roots, referring to “the limitless fields punctuated only by a silo or barn.” It evoked an image of Middle America that effortlessly transported the entire committee back to their own memories of growing up. It was a flawless finesse that allowed him to exclude any reference to his life in the exclusive Long Beach community on Lake Michigan or his selective education at La Lumiere, a college prep school where a jacket and tie were required for classes and the dining hall. He graduated No. 1 in his class in 1973 and was the school’s first Harvard-bound student. Naturally, he graduated from Harvard summa cum laude in 1976, and graduated magna cum laude from Harvard Law.

He would let others plump his resume, while he edited himself down to a plainspoken, modest Midwesterner. Janet Malcolm commented in The New Yorker: “Watching Roberts on television was like watching one of the radiantly wholesome heroes that Jimmy Stewart and Henry Fonda played. It was out of the question that such a man be denied a place on the Supreme Court.”

Roberts was aware of the value of including a vivid metaphor, quotable line or a phrase to memorialize the event and he picked a good one. “Judges are like umpires. Umpires don’t make the rules, they apply them. The role of a judge and an umpire is critical. They make sure everyone plays by the rules, but it is a limited role. Nobody ever went to a ballgame to see the umpire.” That is now a common definition often used when needed.

It was a twist of fate that John Roberts was being interviewed for Chief Justice. On July 19, 2005, President Bush had nominated him to fill the vacancy created by the retirement of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. While this nomination was still pending, on Sept. 3 Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist died from thyroid cancer. During the process of selecting Justice O’Conner’s replacement, Bush had solicited the opinion of several young lawyers in the White House. One was Brett Kavanaugh, who had been nominated to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals. Kavanaugh told him that both Roberts and Samuel Alito would be solid choices, but the tiebreaker would be who was most capable of convincing their colleagues through persuasion and strategic thinking. On this basis, Roberts was clearly the best.

After the Hurricane Katrina disaster that August, President Bush had no appetite for controversy. Reports on Judge Roberts’ interviews in the Senate were going so well that he changed Roberts’ nomination to Chief Justice. That would delay the O’Conner replacement for several months and the court would have to operate with only eight members. This was fortunate, since a highly unqualified Harriet Miers, who worked for Bush in the White House, was the lead candidate to replace O’Conner … and with more time to consider her credentials, saner heads prevailed.

The next three days of hearings offered an exquisite buffet for addicts like me. It started with a round of 10 minutes per senator and it was mildly amusing when Senator Joe Biden’s pontificating took so long that he ran out of time before asking a single question. Judge Roberts displayed remarkable intellect – and a wry sense of humor – when discussing important Supreme Court cases. When Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina asked Roberts what he would like future historians to say about him, Roberts joked: “I’d like for them to start by saying, ‘He was confirmed!’”

Questions fell into a regular rhythm and Roberts answered them almost effortlessly. In addition to his education and experience, the “Murder Boards” – the phrase used for pre-hearing rehearsals – must have really fine-tuned every aspect of what was anticipated. Even today, prospective nominees study the tapes of his hearing as part of their preparation. I got the feeling he was being polite to a bunch of partisan senators (all lawyers) without acting too condescending.

Senator Chuck Schumer of New York became so frustrated at one point he said, “Why don’t we just concede John Roberts is the smartest guy in the room.” In another memorable exchange, Schumer complained, “You agree we should be finding out your philosophy, and method of legal reasoning, modesty, stability, but when we try to find out what modesty and stability mean, what your philosophy means, we don’t get any answers. It’s as if I asked you what kind of movies you like. Tell me two or three good movies and you say, ‘I like movies with good acting. I like movies with good directing. I like movies with good cinema photography.’ And I ask, no, give me an example of a good movie, you don’t name one. I say, give me an example of a bad movie, you won’t name one, and I ask you if you like Casablanca, and you respond by saying lots of people like Casablanca.”

Senator Specter started to cut Schumer when Roberts interrupted, “I’ll be very succinct. First, Doctor Zhivago, and North by Northwest.” Yes, there was laughter in the room.

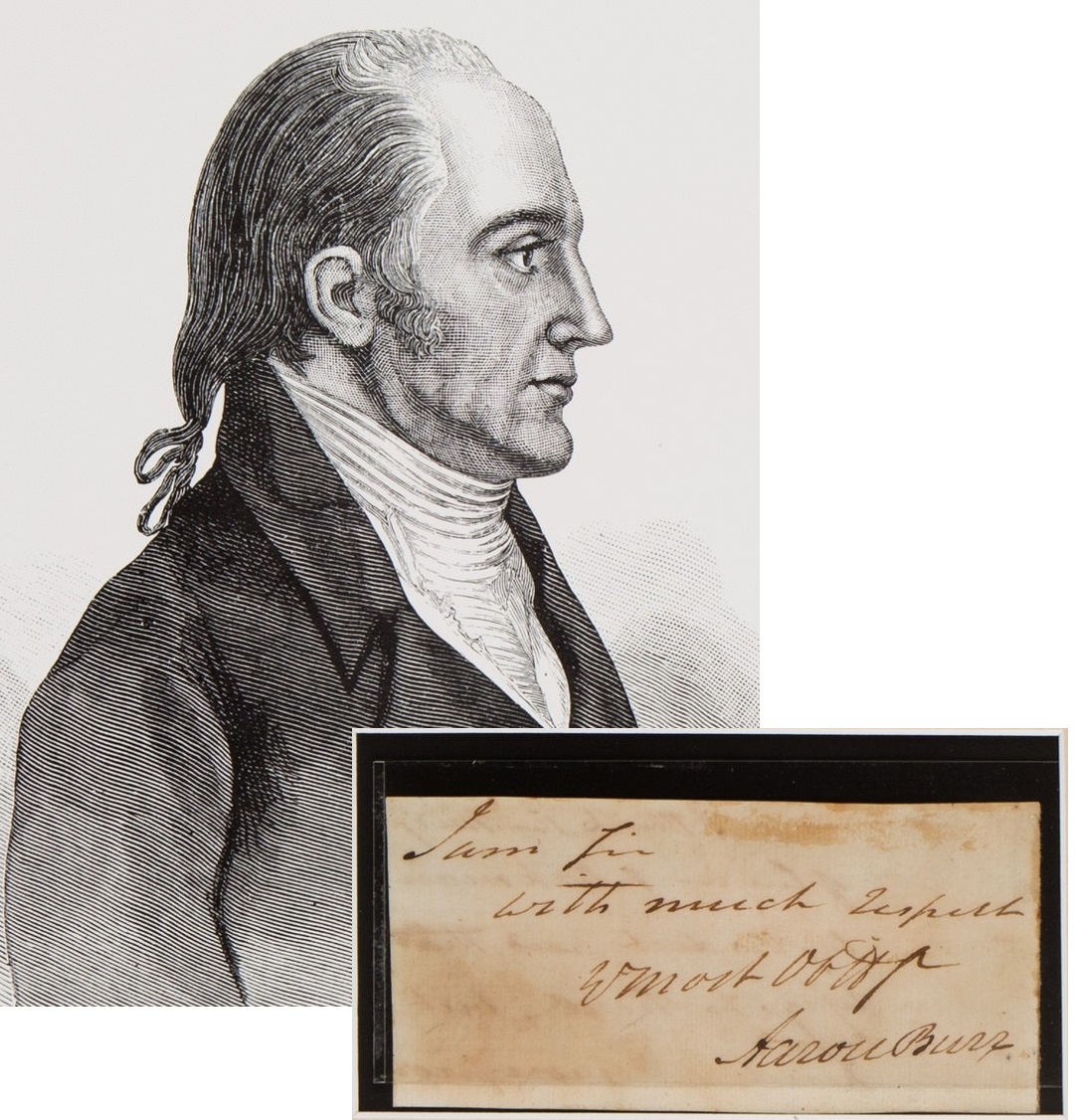

Roberts made it out of the Judiciary Committee on a vote of 13-5 as Democrats found creative excuses to vote no. Then it was on to the full Senate, where he was confirmed 78-22. The 50-year-old Roberts became the youngest Chief Justice since 1801, when the venerable John Marshall (46) was selected.

The Chief Justice is mentioned only once in the Constitution, but not in Article 3, which establishes the judiciary. It is in Article 1, covering Congress, and it says the Chief Justice presides over the Senate during any impeachment of the president (Article 1 Section 3 Clause 6).

The framers vested the Senate with the “sole power to try impeachment” for several reasons. First, they believed senators would be better educated, more virtuous and more high-minded than members of the House. Secondly, it was to avoid the possible conflict of interest of a vice president presiding over the removal of the one official standing between him and the presidency. Of our 45 presidents and 17 Chief Justices, only Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton have been impeached, with Samuel Chase and William Reinquist presiding over their trials. Both were acquitted.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].