By Jim O’Neal

The 59th presidential election in 2020 was unusual in several aspects. Despite the complications of a lethal pandemic, voter turnout was remarkable, with more than 159 million or 66% of eligible voters casting their ballots. In recent years, 40% to 50% has been considered normal, a major slump from the 73% in 1900. Joe Biden’s 51.3% was the highest since 1932 – the first of FDR’s four elections. Both candidates snared over 74 million votes, which topped Barack Obama’s record of 69.5 million in 2008. (Biden’s 81 million is the most any presidential candidate has ever received.)

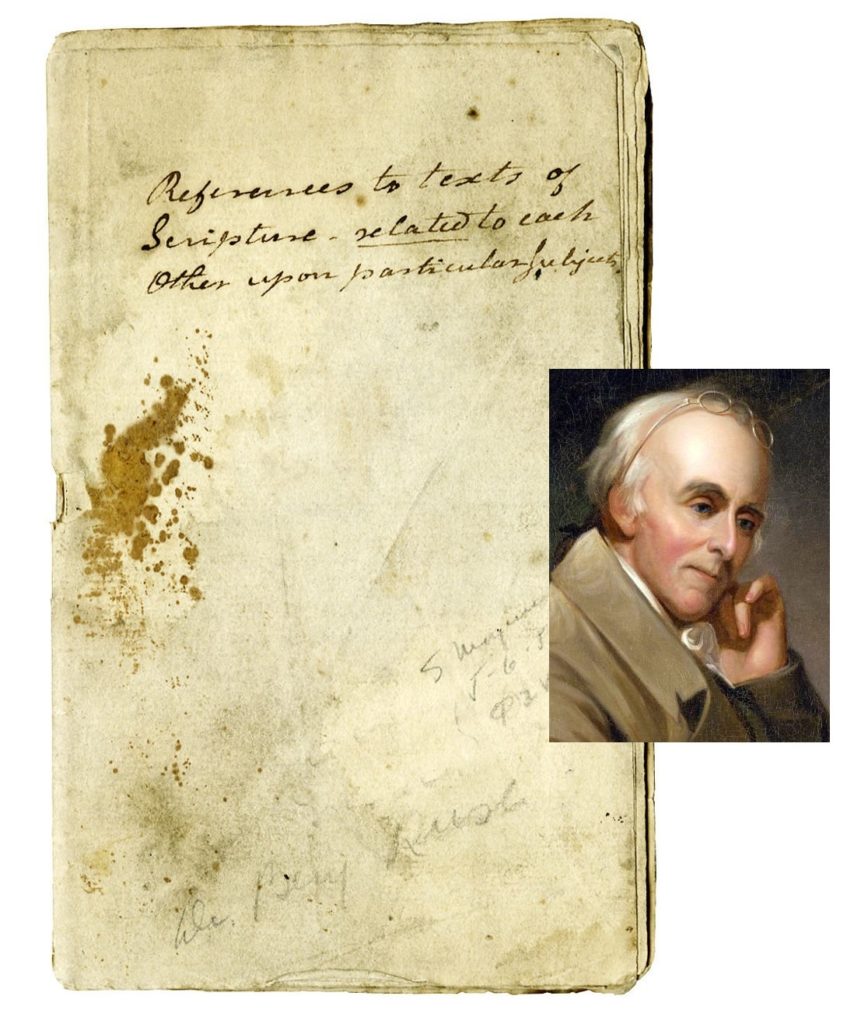

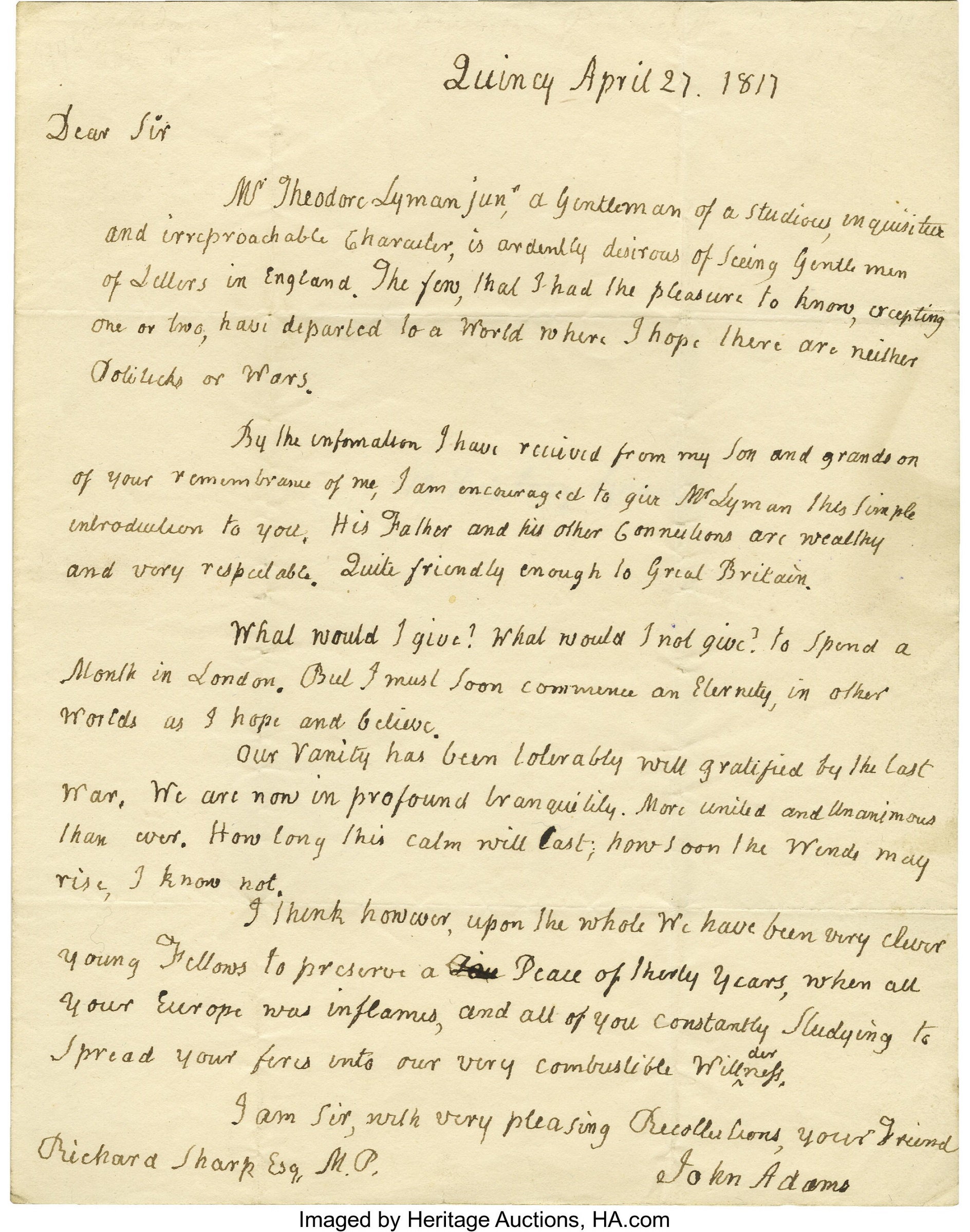

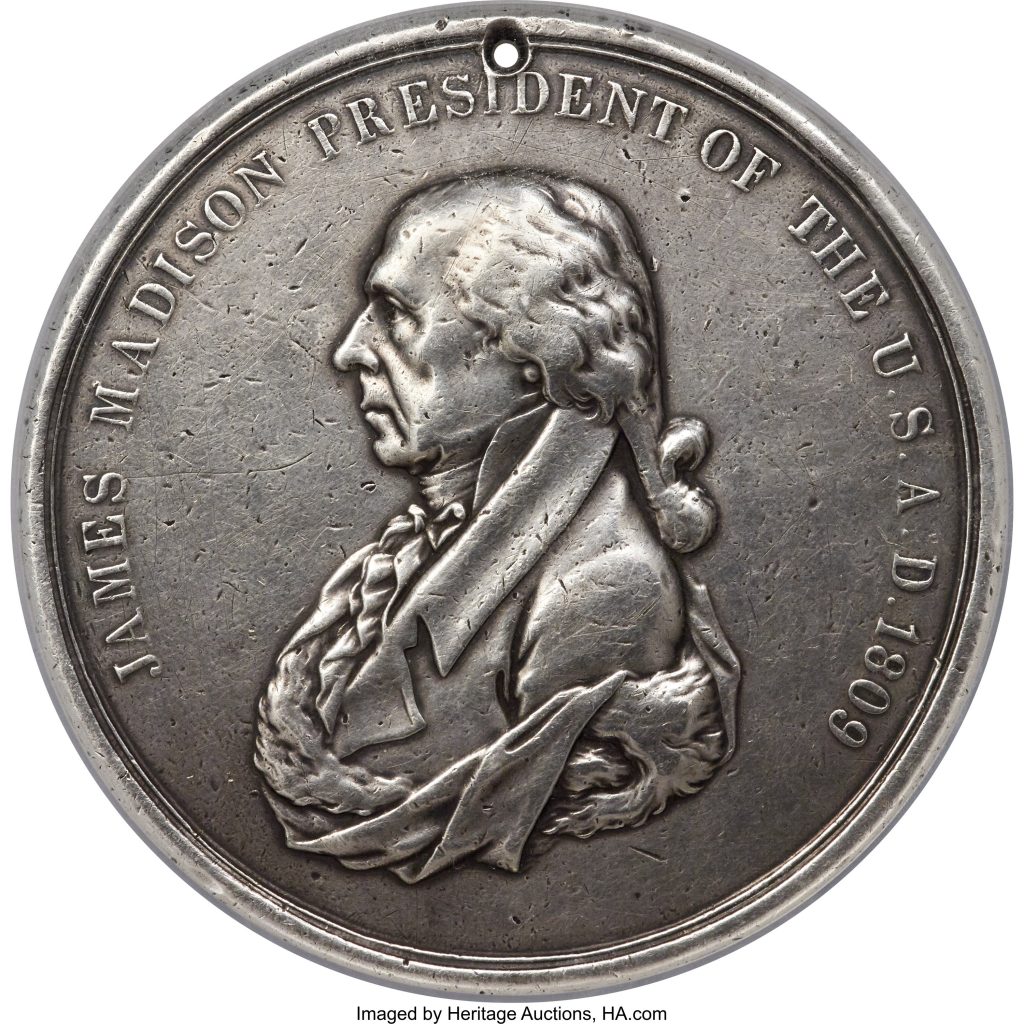

However, it is not unusual for an incumbent president to lose a bid for re-election. Ten presidents before President Trump suffered a similar fate starting with John Adams in 1800. This was the first election where political parties played a role and Adams’ own vice president defeated him.

Another unusual facet of 2020 was the delay in getting all the votes counted and then certified, along with an unprecedented number of legal actions asserting irregularities or voter fraud. Post-election polls indicate that a high percentage of Republican voters still believe that their candidate won. This is unfortunate since the United States has a long, impeccable reputation for smooth, peaceful transfers of power.

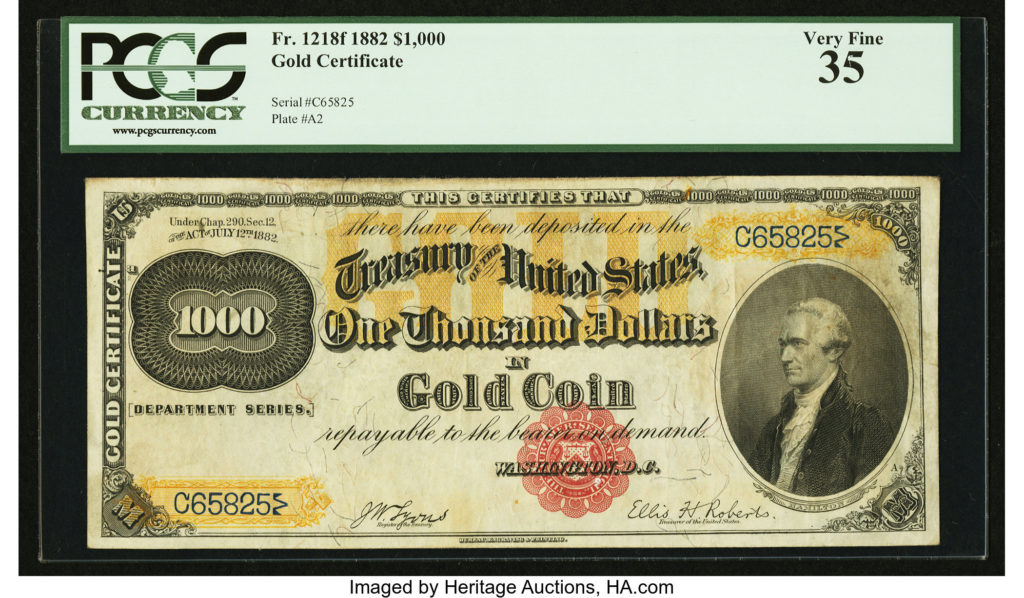

By contrast, throughout recorded history – at least from ancient Rome to modern Britain – all great empires maintained their dominance with force of arms and raw political power. Then, the United States became a global powerhouse and the first to dominate through the creation of wealth. It is a truly remarkable story, liberally sprinkled with adversity, financial panics, a horrendous Civil War and Great Depression without an owner’s manual or quick-fix guide. However, in 1782, Congress passed an act that declared our national motto would be E PLURIBUS UNUM (“One from many”), which, in combination with a culture of “can do,” bound us together and crowded out the skeptics and naysayers. In 1931, “In God we trust” was added just in case we needed a little divine help occasionally.

In the beginning, it was the land.

After Columbus stumbled into the New World while trying to reach Asia by sailing west, Europeans were eager to fund expeditions to this unknown New World. Spain was aggressive and hit the lottery, first in Mexico, followed by Peru. Portugal hit a veritable gold mine by growing sugar in Brazil using slave labor. Even the French developed a remarkable trading empire deep in America using fur trading with American Indians in the Great Lakes area and staking claims to broad sections of land. England was the exception, primarily since they were more focused on opportunities for colonization. The east coast of America had been generally ignored (too hot, too cold, no gold) until Sir Walter Raleigh tried (twice) to establish a viable colony in present day North Carolina. It literally vanished, leaving only a word carved on a tree: Croatoan.

However, the English were still highly motivated to colonize by basic economic pressures. The population had grown from 3 million in 1500 to 6 million in 1650, but without a corresponding increase in jobs. Hordes of starving people naturally gravitated to the large cities and the seaside. The largest was London, and it swelled to 350,000 people by 1650. To exacerbate the situation, the influx of gold and silver into Europe spiked inflation, making a difficult situation unsustainable. In the 16th century, prices rose a staggeringly 400%.

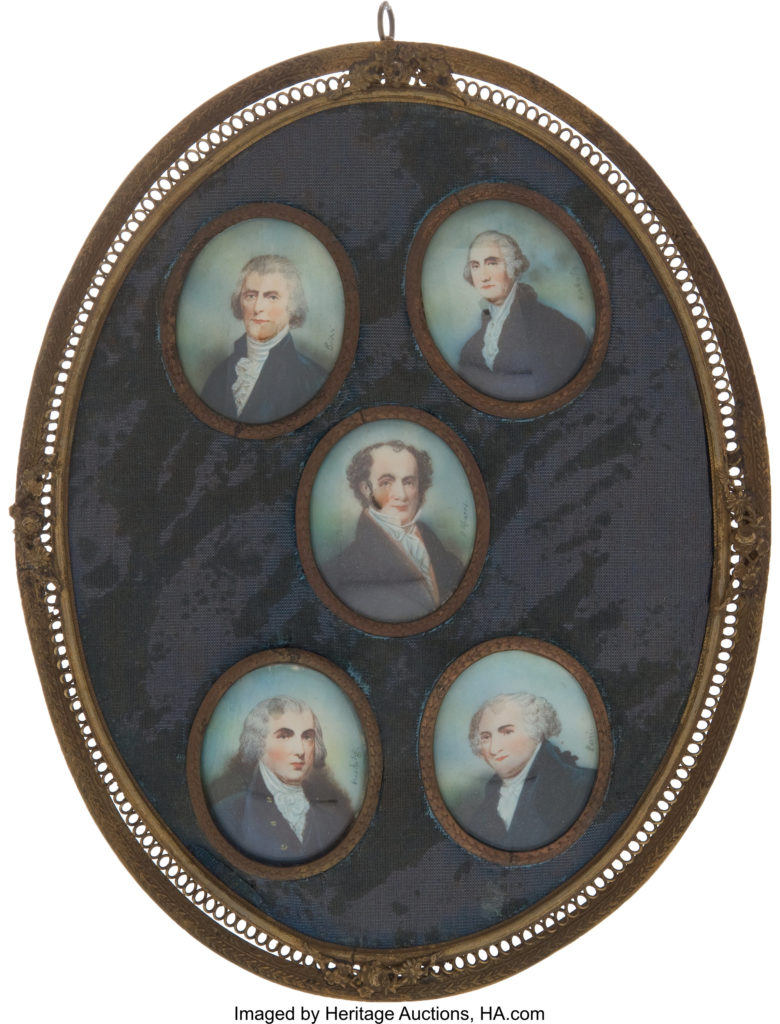

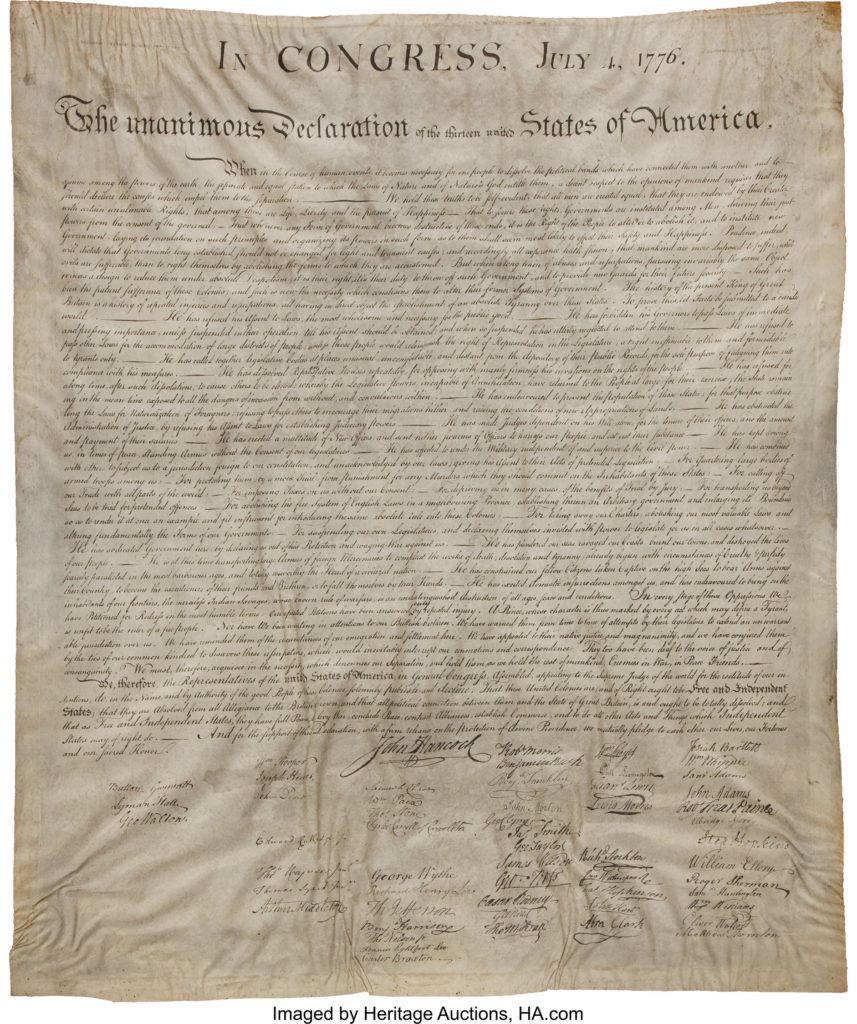

But we are living proof that England’s colonization of the Atlantic coast was finally successful in the 16th and 17th century. Colonial America grew and prospered as 13 colonies evolved into a quasi-nation that was on the verge of even greater accomplishments. However, by 1775 the greed of King George III became too much to tolerate and they declared their independence from Great Britain. The American Revolutionary War lasted seven years (1775-83) and the United States of America was established … the first modern constructional liberal democracy. Losing the war and the colonies both shocked and surprised Great Britain (and many others) and even today historians debate whether it was “almost a miracle” or that the odds favored the Americans from the start.

Then we began to expand across the vast unknown continent due to a series of bold moves. President Jefferson doubled the size of the nation in 1803 with the remarkable “Louisiana Purchase.” President Polk engineered a war with Mexico that concluded quickly with the United States taking control of most of the Southwest, followed soon by the annexation of the Texas Republic. The discovery of gold in the San Francisco area attracted people from all over the world. Despite all of this, not enough has been written about the strategic era just after the end of the Revolutionary War.

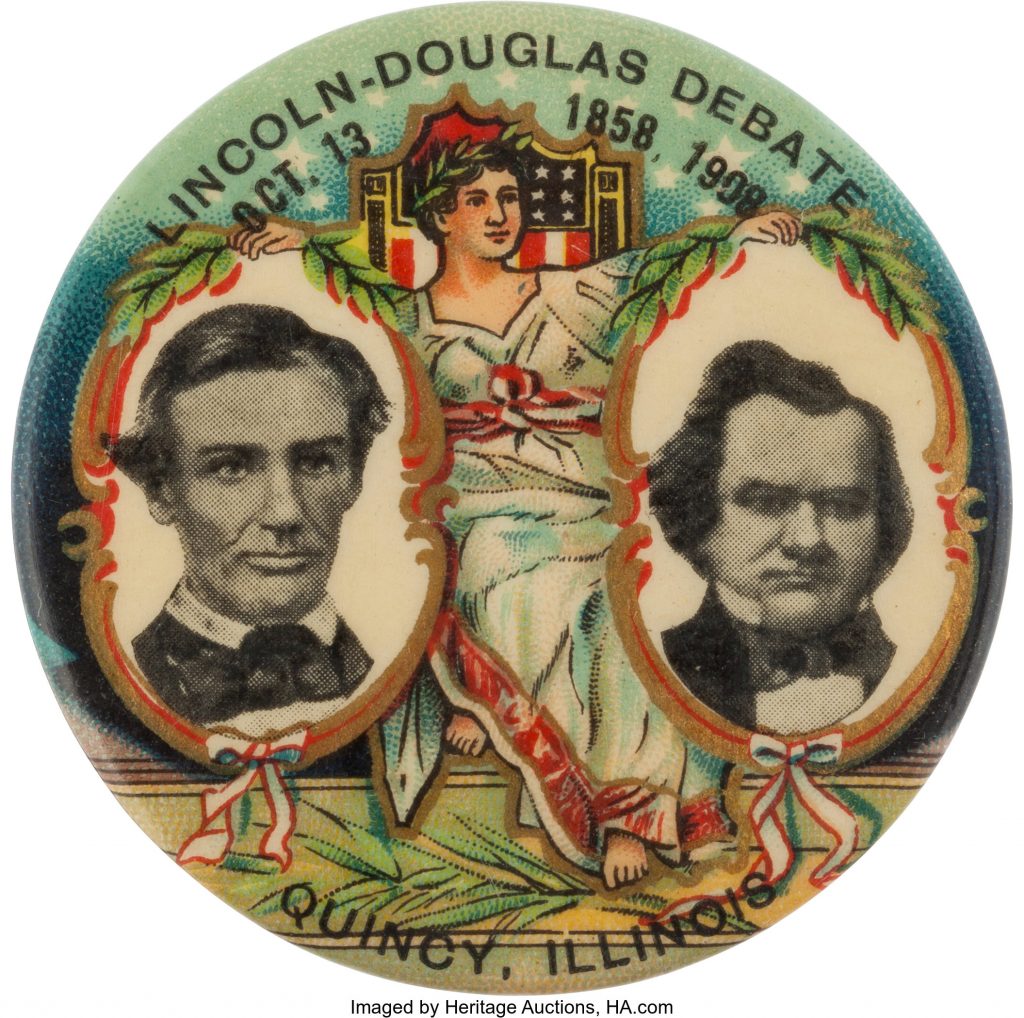

The Treaty of Paris signed on March 1, 1786, did far more than formalize the peace and recognize the new United States of America. Great Britain also ceded (despite objections of France) all the land that comprised the immense Northwest Territory. This was a veritable wilderness area northwest of the Ohio River totaling 265,878 acres, similar to the existing size of America, and containing the future states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and Wisconsin. With this and the Louisiana lands, the United States was eight times larger! In addition, the Northwest Ordinance included three astounding conditions: 1. Freedom of religion, 2. Free universal education and, importantly, 3. Prohibition of slavery.

Also consider that until that point, the United States did not technically own a single acre of land! Now we had an unsettled empire, double the size, north and west of the Ohio River, larger than all of France, with access to four of the five Great Lakes. And then there was the Ohio River itself, a great natural highway west!

This, my friends, is how you build a powerful nation, populate it with talent from all over the world, encourage innovation never seen before, and then trust the people to do the rest. Whenever we are temporarily distracted, have faith that this nation has been tested before and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth. As Aesop and his fables remind … United we stand. Divided we fall.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].