By Jim O’Neal

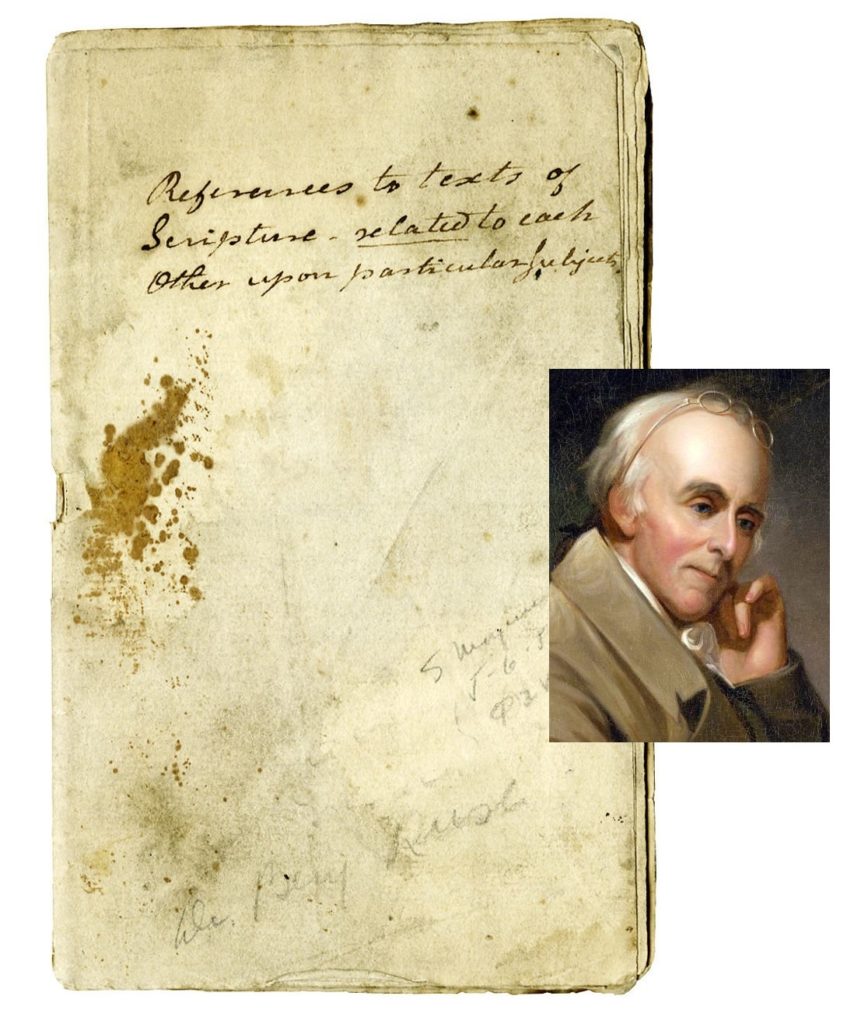

Early in 1813, two former U.S. presidents were in grief over the death of a mutual friend and colleague. Dr. Benjamin Rush had been responsible for reconciling the ex-presidents and healing the bitter rift that had grown worse after they left office. Now, Dr. Rush was dead and both John Adams and Thomas Jefferson were convinced that the eminent physician deserved to be honored for more than his enthusiasm for American liberty.

Benjamin Rush was born in 1746 in a small township a few miles outside of Philadelphia. Just 30 years later, he was one of the younger of the 56 men who bravely signed the Declaration of Independence (Edward Rutledge, age 26, was the youngest). Benjamin was 5 years old when his father died, but in a stroke of pure providence, his mother took notice of his remarkable intellect and was determined to see that her precocious youngster got special tutoring. She sent him to live with an aunt and uncle, who enrolled him in a boarding school run by the Reverend Samuel Finley, an academic who founded the West Nottingham Academy (1744) and later the College of New Jersey (Princeton University).

Rush (predictably) flourished in this rarefied intellectual atmosphere and at age 13 was admitted to Princeton. After graduating in one year, he was then apprenticed to Philadelphia’s foremost physician, Dr. John Redman. However, eager to continue his studies, he sailed to Scotland in 1766. He entered the University of Edinburg, rated the finest medical school in the British Empire. Again, serendipity reigned since this was the blooming of the Scottish Enlightenment. This period was coincidental with the European movement that encouraged rational thought, while resisting the traditional imposition of sovereign authority, especially from Great Britain. By divine providence, the American colonies were gradually drifting into similar territory and the example of taxation was considered undermining independent action, which curtailed liberty.

During the next three years, Rush not only became a fully qualified doctor of medicine, but was exposed to some of the greatest thinkers, politicians and artists that were alive. When he returned to Philadelphia, his bandwidth had continued to expand as he absorbed radical alternatives to conventional theories. He became obsessed with the concept of public service and a champion of the common man.

Establishing a medical practice was challenging since the poor represented the equivalent of today’s middle class and the wealthy naturally controlled the best and most experienced practitioners. Since Rush was now eager to help close social inequalities, he sought out the sick in the slums of Philadelphia and offered his services. He was forced to accept a position as professor of chemistry at the College of Philadelphia to bolster his income (his family had grown to 13) and, importantly, provide an outlet for his prodigious medical papers.

He is credited with being the first to highlight the deleterious effects of alcohol and tobacco, but in the process alienated both heavy users and most producers. Even more controversial was his anti-slavery position with the South growing more reliant on slave labor as the integral part of their agrarian economic development. With Great Britain seemingly intent on oppressing all Americans, the nation was inevitably being drawn into war. Dr. Rush was eager to leverage his medical skills to assist the military and was appointed Surgeon General of part of the Continental Army. His broad experience resulted in a pamphlet called “Directions for Preserving the Health of Soldiers.” He keenly observed that “a greater proportion of men have perished with sickness in our armies than have fallen by the sword.” Looming in the future, the Civil War and World War I would prove just how prescient he was.

Today, Dr. Benjamin Rush is generally forgotten or relegated to the second tier of Founding Fathers, an oversight that even Adams and Jefferson recognized when he died in 1813. It is a curious situation when one considers the sincere eulogies expressed by his colleagues and students. It’s estimated that he trained 3,000 doctors and his writings, both personal and technical, are astonishing in breadth and depth. Jefferson was effusive with his praise and John Adams declared he “knew of no one, living or dead, who had done more real good in America.” High praise from two such prominent men who were there to witness it.

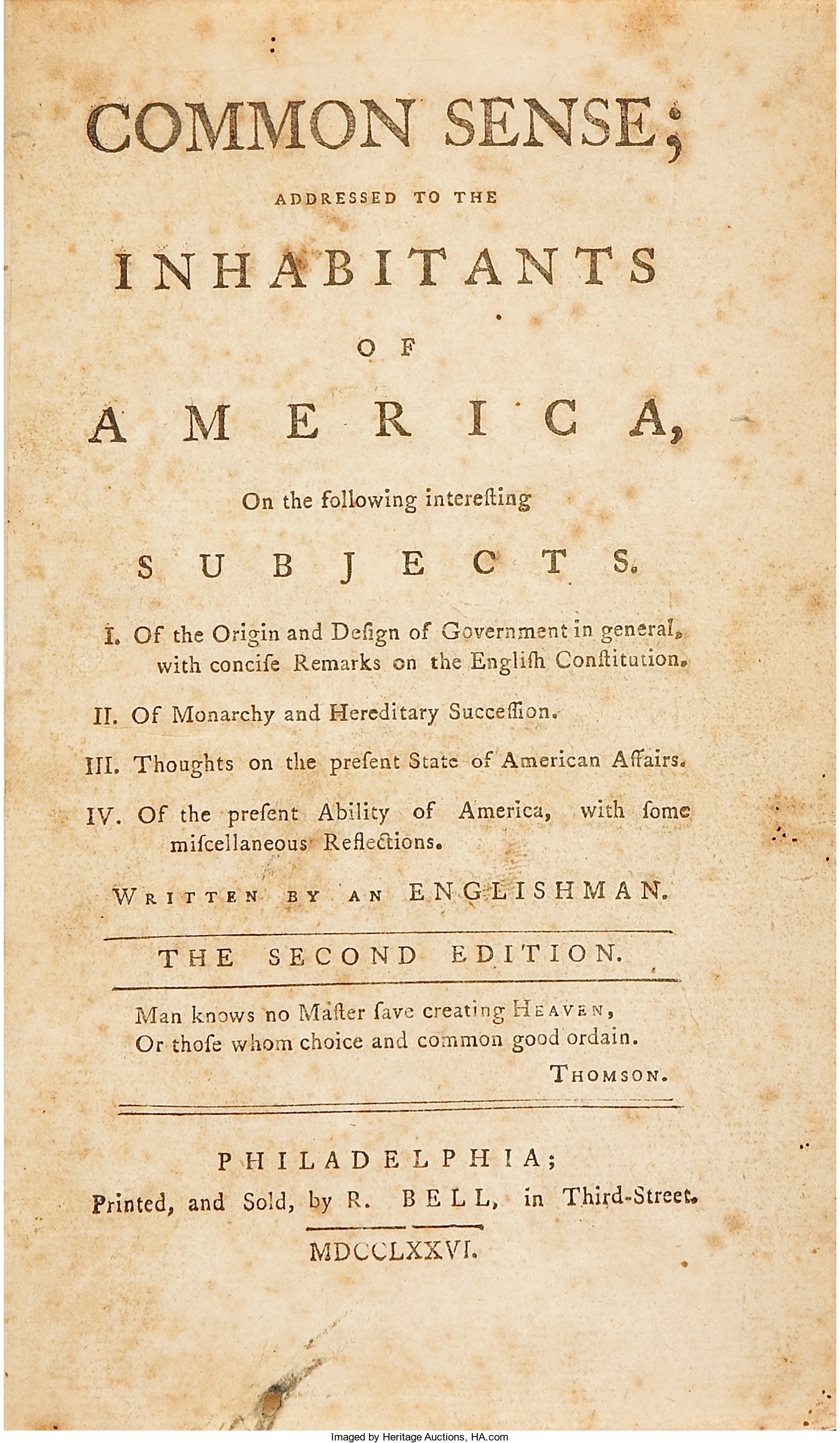

Another man who benefited from association with Rush was the firebrand Thomas Paine, who generally falls into the same category. His publication of Plain Truth is one of the most powerful forces behind the colonies’ quest for independence from the British Crown. Never heard of it? That’s not surprising since Plain Truth was changed to Common Sense after Dr. Rush had Paine read him every line before it was published. He persuaded Paine to make the change and it remains the best-selling book in American history and set the colonies firmly on the road to independence.

When I view the current political landscape, I’m persuaded that all that’s missing is … Common Sense!

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].