By Jim O’Neal

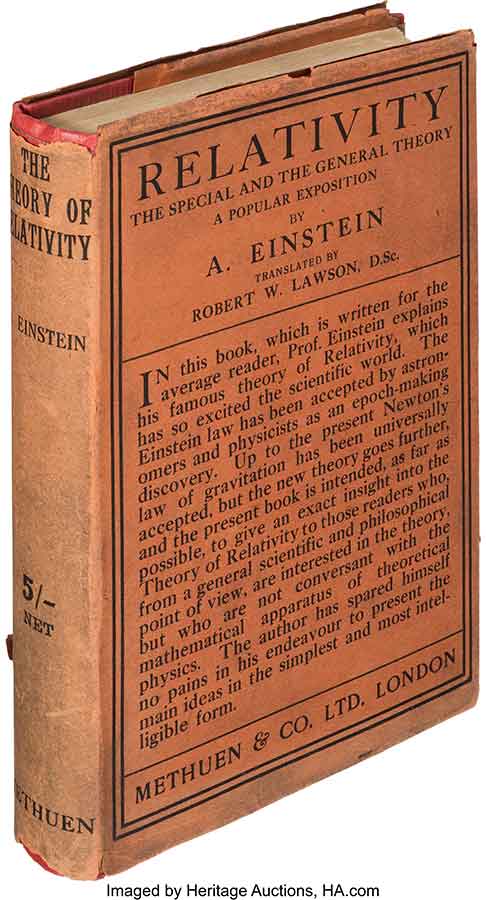

While watching TV someone mentioned Principe and it piqued my interest, primarily because I knew so little about this relatively small island off the West Coast of Africa in the Gulf of Guinea. After digging a little deeper, I discovered Principe was where Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity was corroborated by a gifted mathematician, Sir Arthur Eddington, during a total solar eclipse.

The date was May 29, 1919.

To fully understand the sequence of events, it helps to start about 75 years earlier.

During the 19th century, the map of Europe was frequently redrawn as old empires crumbled and new powers emerged. You may not know that in 1850, the countries of Germany and Italy that we know so well today did not exist. Instead, there were many German-speaking and Italian-speaking states, each with their own leaders.

Then in the 1860s and 1870s ambitious politicians started merging these states through a combination of hostile actions and political agreements. A prime example was the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. The German states, led by Otto von Bismarck (the “Iron Chancellor”), defeated France soundly. This ended France’s domination of Europe and forced Napoleon into exile in Britain.

The formerly feuding 25 German principalities were transformed into a new unified German Empire on January 18, 1871. The new superpower had an enormous Army, a streamlined economy and intellectual institutions that dwarfed the European continent. The seeds of Germanic militarism would plague the world well into the 20th century. Following a visit by the peripatetic Mark Twain in 1878 he wrote, “What a paradise this land is! Such clean clothes and good faces, what tranquil contentment, what prosperity, what genuine freedom, what superb government! And I am so happy, for I am responsible for none of it. I am only here to enjoy.” High praise for a country that would wreak havoc upon the world twice in the next century.

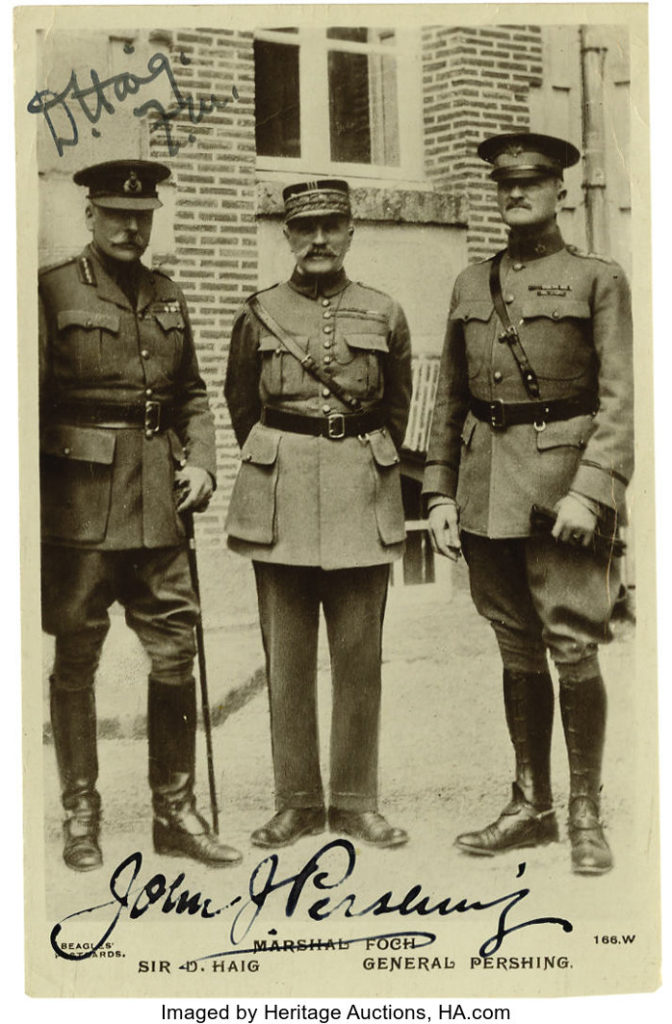

By the turn of the 20th century, a peculiar devolution emerged with a complicated network of alliances and rivalries. When the heir to the Austrian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, was assassinated by a Serbian nationalist in June 1914, Austria declared war on Serbia. Then the others followed like a line of dominoes cascading helter-skelter. In Europe the fighting took place on two fronts: the Western Front, stretching from Belgium to Switzerland, and the Eastern Front, from the Baltic to the Black Sea. Then it quickly spread to the European colonies throughout the world. The war raged for four and a half years, and more than 20 million lost their lives.

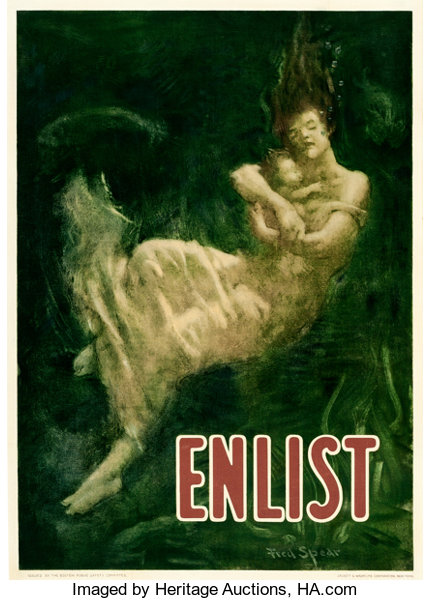

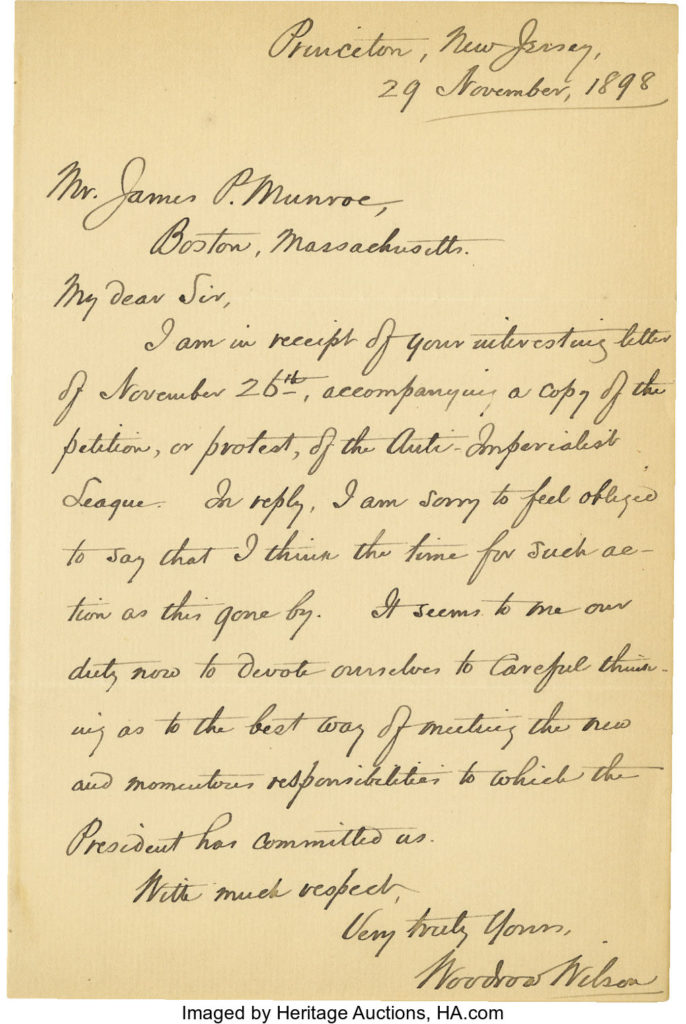

In the United States, seemingly isolated by two great oceans, President Woodrow Wilson was re-elected in 1916 under the slogan “He kept us out of war.” Five months later he asked Congress to declare war against Germany, and 60 days later American troops landed in France. The distant sounds of guns had somehow morphed into a cacophony of a world war.

At the time, very few were aware of the effects the Great War had on Einstein’s efforts to prove his general theory of relativity. The industrialized slaughter bled Europe from 1914-1918 without regard for the weak or strong, the right or the wrong. Wars do not have a conscience or any pity for the young or old. Their objective is destruction. Men make these decisions.

At age 39, Einstein was working in Berlin, literally starving due to food blockades. He lost 50 pounds in three months and was unable to communicate with his closest colleagues. He was alone, honing his theory of relativity, hailed at birth as “one of the greatest — perhaps the greatest — of achievements in the history of human thought.” This was the first complete revision of our conception of the universe since Sir Isaac Newton.

Scientists seeking to confirm Einstein’s ideas were arrested as spies. Technical journals were banned as enemy propaganda. His closest ally was separated by barbed wire and U-boats. Sir Arthur Eddington became secretary of the Royal Astronomical Society and they secretly collaborated. It was actually Eddington who supplied Einstein’s astonishingly mathematical work to help prove the theory. He was convinced that Einstein was correct. But how to physically prove it?

In May 1919, with Europe still in the chaos left by war, Eddington led a globe-spanning expedition to catch a fleeting solar eclipse on film. This confirmed Einstein’s boldest prediction that light has weight and could be bent around an orbiting object — in this case Earth itself. The event put Einstein’s picture on front pages around the world!

Later, on August 2, 1939, he would write a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt warning him that an atomic bomb was feasible and the Germans, with all their talented rocket scientists, could be dangerously close to making one. He encouraged the president to secure a supply of uranium and make it a priority.

We now know how this ended.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].