By Jim O’Neal

World War I officially erupted in Europe on July 28, 1914. The following month, British commentator and author H.G. Wells wrote a series of articles that blamed the Central Powers (Austria-Hungary, Germany, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire) for starting the war. Wells also argued that eliminating militarism in Germany was essential to avoiding future wars. Subsequently, the articles appeared in a small book titled The War That Will End War. The book’s title was far too optimistic, but Mr. Well’s thesis about Germany’s military would prove to be eerily prophetic.

As the war inexorably spread throughout Europe, conventional wisdom dictated that the United States would never become directly involved due to long-standing political policies dating to its founding. George Washington’s famous Farewell Address in 1789 had warned us to “steer clear of permanent alliances” and Thomas Jefferson echoed these sentiments: “Peace, commerce and honest friendship with all nations … entangling alliances with none!”

The Germans were confident America would remain on the sidelines. Their surprisingly broad network of spies in the United States kept reassuring them of the strong sentiment to avoid foreign wars and misinterpreted pacificism as a sign of weakness. It had only been 49 years since the end of hostilities in the Civil War and the ashes were still warm. Furthur, the American army was small (ranking 17th in the world), had not been involved in any major operations, and lacked the modern equipment of the 20th century.

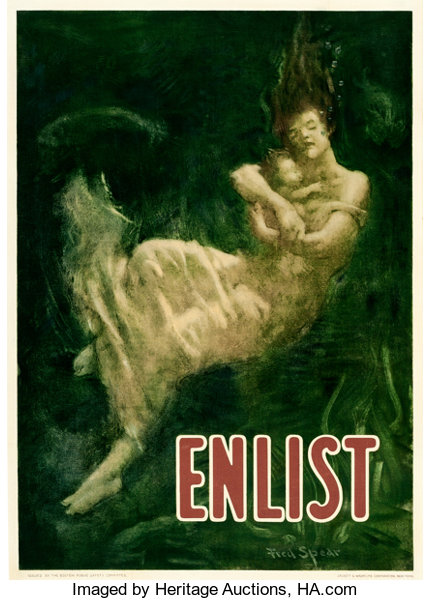

President Woodrow Wilson had been re-elected in 1916 under the slogan “He Kept Us Out of War” and the promise of four more years of peace was comforting. It further emboldened the Germans and they became even more provocative by implementing an “unrestricted” policy for their fleet of U-boat submarines in the Atlantic. They pledged to attack any ship irrespective of cargo or innocent civilians to buy enough time to conquer Great Britain. However, the sinking of the Lusitania proved to be one step too far.

On April 2, 1917 at precisely 8:30 p.m., President Wilson assembled both Houses of Congress, the Supreme Court and his Cabinet. In a 36-minute speech, he outlined the vicious attacks by Germany on our ships and the innocent lives lost. Finally, he concluded by formally requesting Congress to declare war on Germany (only). The final words were lost or unheard amid the boisterous cheering and flag-waving. Later, back at the White House, he expressed his feelings of wonderment and commented to his aides: “Just stop and think about what they were applauding…” Finally alone, he wept almost silently.

On April 6, Congress declared war on Germany and by June 25, the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) arrived in France, led by General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing. On July 4, Independence Day, elements of Pershing’s force paraded in Paris. Pershing holds the distinction of being the first living general to be promoted to general of the Armies and allowed to select his own insignia. He chose four gold stars to distinguish his rank from generals who wore four silver stars. There is no record of any familial relationship to either of the Pattons.

Throughout the months that followed, fresh units continued to be added and World War I would end on the memorable point of time of 11 a.m. on the 11th day of the 11th month in 1918. President Wilson was awarded the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize, but was unable to convince the U.S. Congress to join the League of Nations. Absent the United States, there was not much hope in helping Europe avoid another war. It was time to bring the boys home. Among them was a young lieutenant who would rise to prominence as the supreme commander of U.S. forces when we returned 20-plus years for the second round of fighting.

In comparison to the choices of today, I REALLY like Ike!

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].