By Jim O’Neal

The most popular radio show in America in the mid-1930s was NBC’s The Chase and Sanborn Hour. A variety show, it featured the antics of ventriloquist Edgar Bergen and his sidekick Charlie McCarthy. By 1938, it was so dominant that competing network CBS could not find a sponsor willing to back a show to go against it.

In semi-desperation, the network commissioned Orson Welles, a 23-year-old director who had thrilled theater critics with his unusual staging of Macbeth, set in Haiti with an all-black cast. He agreed to provide CBS each week with a one-hour, commercial-free drama aired directly against Bergen on Sunday nights.

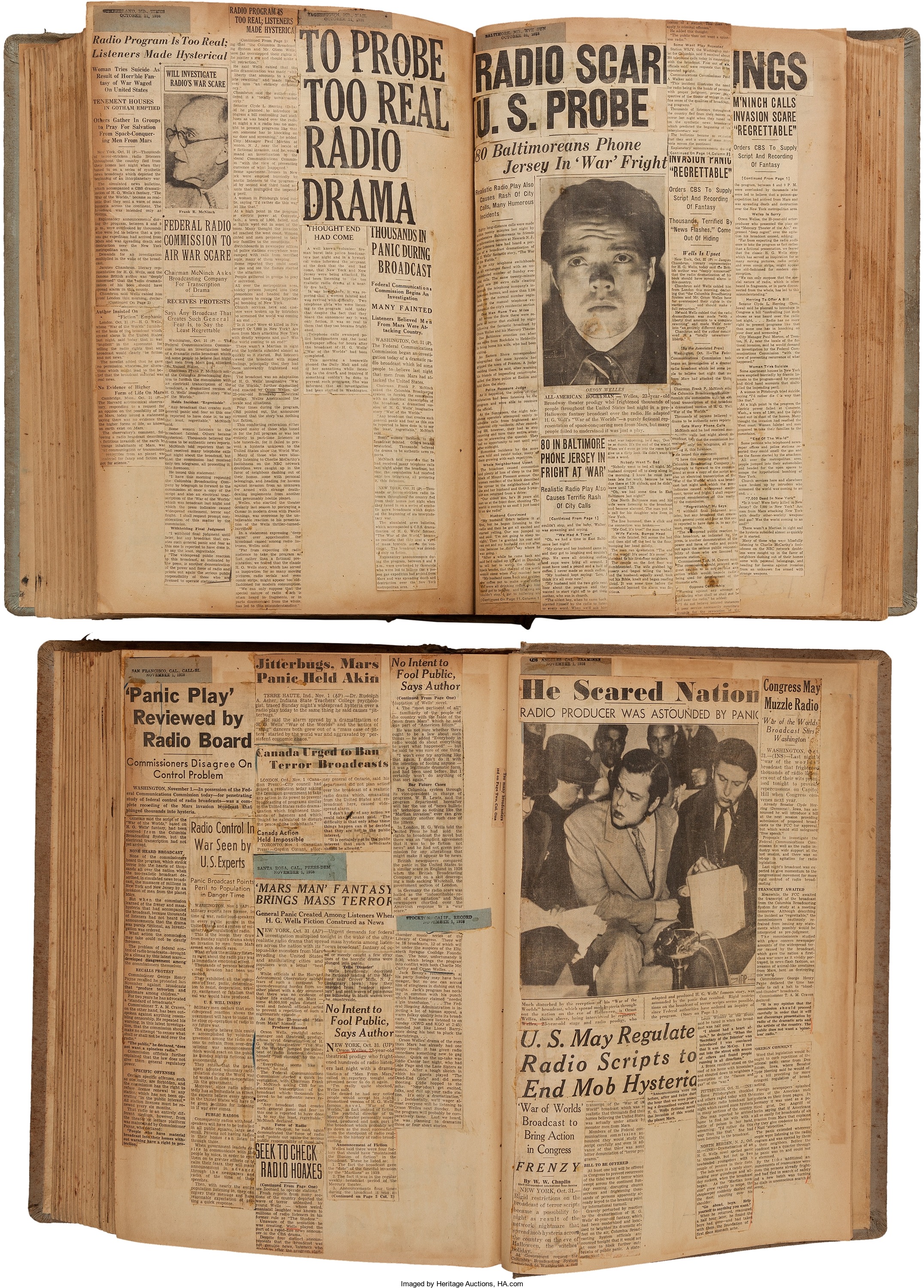

On Oct. 30, 1938, Welles’ Mercury Theater opted to present a radio play based on H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds. However, at the last minute, the young director decided to exploit the reputation of radio as the medium of truth and offered the play as realistically as possible. They began as if they were presenting an evening of ballroom music and then interrupted the band with a sudden announcement that Martians had landed on a farm near Grover’s Mill, N.J. From there, the story unfolded much as a real crisis might, with radio reporters relaying dispatches from the scene.

“Ladies and gentlemen, this is the most terrifying thing I have witnessed…,” sobbed Welles’ correspondent as he encountered the invaders. “There, I can see the thing’s body. It’s large as a bear and glistens like wet leather… the eyes are black and green like a serpent. The mouth is V-shaped with saliva dripping from its rimless lips.”

In the course of a single hour, Welles’ Martians landed on Earth, constructed deadly ray machines, defeated the American Army, destroyed radio communications and occupied large sections of the country. Remarkably, hundreds of thousands of Americans believed every word of it.

Radio stations were inundated with calls from listeners gripped with fear. Train stations were crowded with families demanding tickets “anywhere.” In New York City, theaters were emptied in panic and in Northern New Jersey – the site of the Martian landing – roads were jammed with people in cars packed with precious belongings, fleeing extraterrestrial annihilation.

When Welles signed off at 9 p.m., police were ready to arrest him, but he had broken no laws and the FCC only issued a mild reprimand.

His program had touched a sense of apocalypse that dominated the lives of many people in the late 1930s. Everywhere they looked, there were signs that things were going deeply awry. The American economy had remained stubbornly stagnant; one-third of the people were “ill-housed, ill-clad and ill-nourished,” in FDR’s own words.

Even nature looked like an enemy. Only a month before, the East Coast had endured a storm of such mammoth proportions that it felt like an invasion, as well. The Hurricane of 1938 caused more damage than the Chicago Fire and more deaths than the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Seven hundred people were killed and the homes of more than 63,000 people were destroyed. Forty-foot waves crashed against Long Island, with ocean spray felt as far north as Vermont.

Yet even as people struggled to keep food on the table and their homes on the ground, it was the rumblings of war around the globe that jangled nerves. First, it was Italy seizing Ethiopia, then a civil war in Spain, and the Nazis in Germany making preparations for more war in Europe (again). But this time, most Americans were convinced we would never get involved in these foreign affairs and even had promises of “no American boys in foreign wars” from our leaders.

Twelve years later, after a global war ended with the dropping of two atomic bombs, America would make a fresh start with the glorious 1950s — after all, this is the United States! — and leave all that gloomy pessimism behind us forever.

And so we will again.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].