By Jim O’Neal

With the specter of another depression on America’s horizon, my mind flashes back to the past and sad irony of Herbert Hoover. He was born in 1874 in West Branch, Iowa – the first president born west of the Mississippi River. An orphan at the tender age of 9, he was taken in, luckily, by relatives in Oregon. The Minthorns were Quakers like his parents and they taught him the value of community service and hard work.

In 1891, he enrolled at Stanford University, the first year that classes were open. He was a geology major and after graduation ended up in London with a company investigating gold deposits in Western Australia. While at Stanford, Hoover dated Lou Henry, a fellow geology major and the first female to earn a degree. Hoover proposed to her in a telegraph from Australia and they were married in California in February 1899 – two mining engineers … both intrepid travelers.

Together they set off for China, where Herbert discovered coal deposits. The hard work earned him a junior partnership with his London-based employer. This was followed by a stint in Tientsin just in time for the Boxer Rebellion in 1900 when Chinese rebels rose up against colonial powers. The couple became fluent in Mandarin, a skill they would use later in the White House to communicate in private without the WH staff listening in.

Next was a series of trips starting in Burma (silver, lead and zinc), copper and oil in Russia, and then back to Australia in a quest for more zinc. After forming his own company in 1908, their fortunes began to accumulate and by 1913 exceeded $4 million. After the United States entered World War I in 1917, President Wilson asked Hoover to manage America’s domestic food supplies. In Washington, D.C., he was successful in establishing programs to control prices, eliminate waste and promote conservation by the public. His managerial reputation was beginning to grow and his ability to cut through government bureaucracy produced results almost unprecedented in American history.

After flirting with the presidency in 1920, the ultimate winner, Warren Harding, selected Hoover to become the third Secretary of Commerce. When Harding died unexpectedly in 1923, President Calvin Coolidge retained Secretary Hoover in the Cabinet. Coolidge had observed Hoover’s work and decided to expand his formal duties. He put him in charge of the American Relief Administration to assist the recovery of post-war Europe. Hoover was more than qualified and had played a role in assisting thousands of Americans get back home when the war exploded in 1914. In addition, he had helped Belgium and France from starvation after the German invasions.

He soon became universally recognized as the greatest humanitarian alive in the world. In addition to being widely admired, he had the distinction of having an orbiting asteroid, Hooveria, named in his honor. Earlier, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt had proclaimed, “Hoover is certainly a wonder and I wish we could make him president of the United States! There could not be a better one.”

By 1928, Coolidge had tired of Washington and chose not to run for reelection. The 54-year-old Herbert Hoover was certainly not tired and was eager to demonstrate his extensive experience by expanding America’s fortunes even further. He easily defeated Al Smith, the governor of New York, with help from anti-Catholic voters and the burden of corruption associated with the infamous Tammany Hall group. The newspapers excitedly touted Hoover as an innovator and set high expectations for his administration. In his inaugural address, the new president confidently declared, “I have no fears for the future of our country. It is bright with hope!” The joy of his Inauguration day, March 4, 1929, seems totally incongruous with the events of the next four years.

Just seven months after he entered the White House, economic trouble trashed his campaign prediction about “being near the final triumph over poverty.” On Oct. 24, 1929, panic enveloped the New York Stock Exchange when almost 13 million shares changed hands. There was a short respite, but on Tuesday, Oct. 29, the market basically collapsed, heralding the beginning of the Great Depression. No one expected the Depression would last a full decade, including the American Economic Association. Virtually all the experts assumed it would be a matter of months until the normal business cycle resumed. Scholars are still debating the cause of the Depression and the stock market crash is only one of the contributing factors.

Just as it was one of the factors that cost Hoover his job. He didn’t cause the crash, but an episode in 1932 certainly contributed. In 1924, President Coolidge vetoed a bill to pay war veterans a bonus to compensate them for loss of income during their military service. However, Congress overrode his veto and the money was to be paid in 1945. In 1932, 20,000 veterans marched on Washington hoping to get an advance payment to alleviate Depression hardships. Congress was considering a Bonus Bill, but President Hoover opposed it and the Senate rejected it. Veterans turned their sights on the Capitol Building, marching for three days and four nights in a “Death March.”

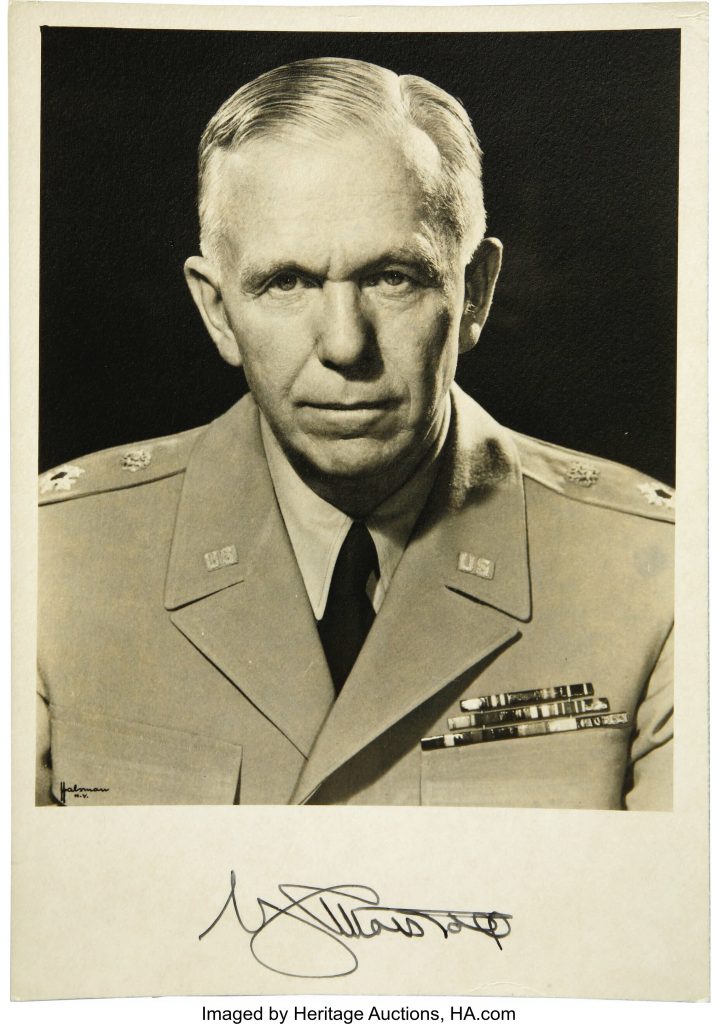

President Hoover ordered General Douglas MacArthur to force them back into temporary camps. MacArthur overreacted, using cavalrymen with drawn sabers and an infantry with tear gas. Six tanks joined the fray under Major George Patton. The soldiers attacked the camps and the angry veterans set their own huts on fire in protest. Colonel Dwight Eisenhower was shocked at MacArthur’s treatment and later said, “It was a pitiful scene, ragged, discouraged people burning their own little things.” The excessive use of force, especially against veterans, disgusted most Americans. Then Hoover made it worse by deriding the bonus marchers as rabble and refusing to criticize MacArthur.

When Democratic presidential candidate FDR heard about the fiasco, he simply said, “This will elect me.”

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].