By Jim O’Neal

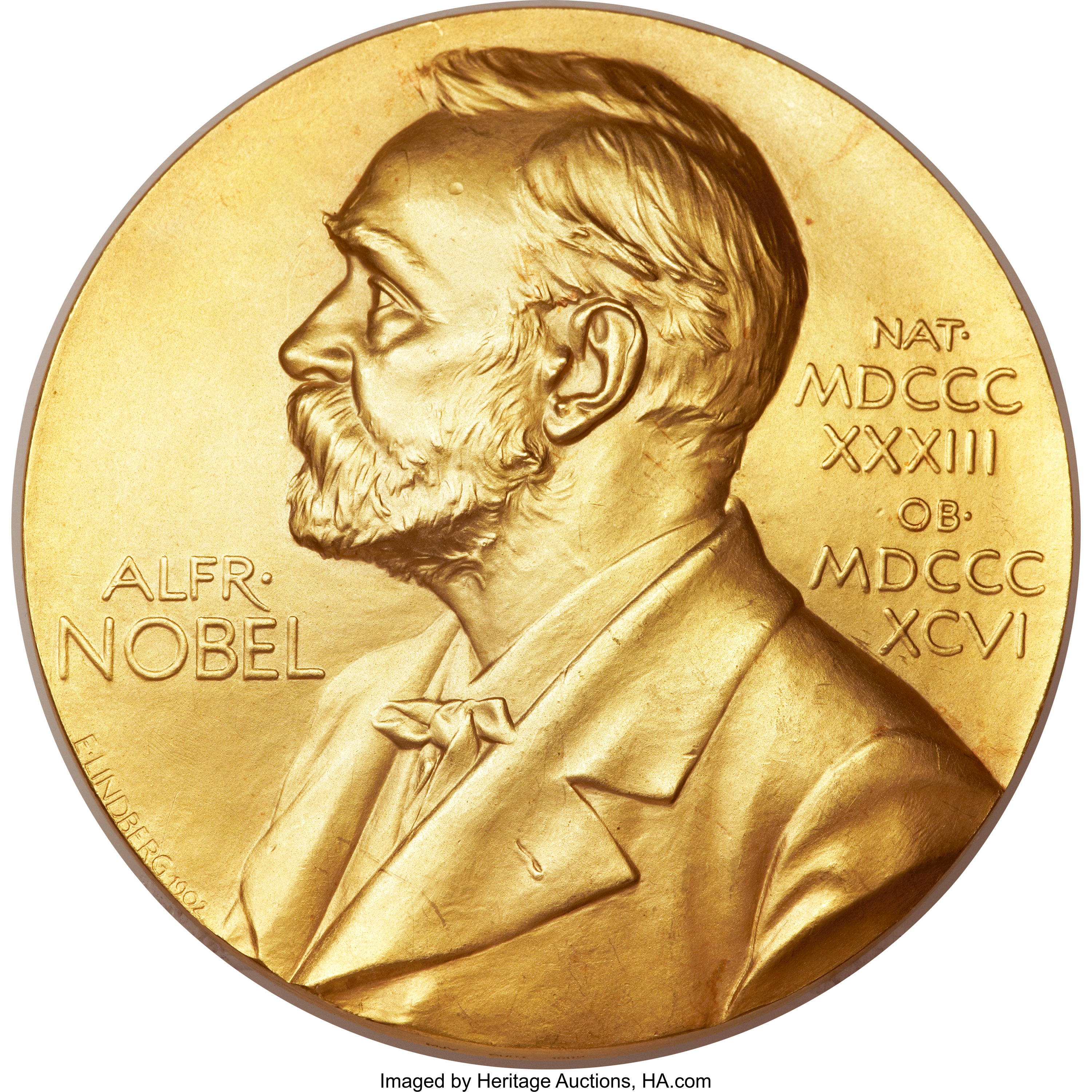

In 1888, a French newspaper published Alfred Nobel’s obituary with the following title: “Le marchand de la mort est mort” or “The merchant of death is dead.”

In reality, it was actually his brother Ludvig who had died, but Alfred was appalled that this kind of sendoff could tarnish his own professional legacy. One presumes that the only error was the mix-up in names since the sobriquet seemed apt given Alfred’s contributions to the effectiveness of substances that resulted in death.

In a complicated maneuver, the inventor of dynamite attempted to rectify future obits by posthumously donating the majority of his estate (94 percent) to the establishment of the Nobel Prizes, designed to expunge his reputation for all the deaths resulting from his explosive product. It was only partially successful since he was accused of treason against France for selling Ballistite (a smokeless propellant composed of two explosives) to Italy. The French forced him to leave Paris and he moved to Sanremo, Italy, where he died in 1896. There were five Nobel categories with an emphasis on “peace” … for obvious reasons.

A native of Stockholm, Nobel made a fortune when he invented dynamite in 1867 as a more reliable alternative to nitroglycerin. As a chemist and engineer, he basically revolutionized the field of explosives. Some accounts give him credit for 355 inventions. In 1895, a year before his death, he signed the final version of his will, which established the organization that would bear his name and “present prizes to those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit to mankind.”

Nobel’s family contested the will and the first prizes were not handed out until 1901. Among the first winners were German physicist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, who discovered X-rays, and German microbiologist Emil Adolf von Behring, who developed a treatment for diphtheria. The Nobel Prizes were soon recognized as the most prestigious in the world. Except for war-related interruptions, prizes have been awarded virtually every year. The category of economics was added in 1969.

The first American to receive a Nobel was President Theodore Roosevelt, who garnered the prize in 1906 after he helped mediate an end to the Russian-Japanese war. The German-born American scientist Albert Michelson claimed the physics prize the next year. However, the peace and literature prizes would become the most familiar to Americans and are some of the most controversial. Critics voiced concerns over Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson (1919), George Marshall (1953) and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger (1973). More recently, winners have included Al Gore (2007) for making an Oscar-winning documentary on climate change, and Barack Obama (2009) “for his extraordinary efforts to strengthen international diplomacy and cooperation between peoples.” (for more, see Obama’s Wars by Bob Woodward).

William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck and Toni Morrison generally have escaped criticism, as have multiple winners like Marie Curie (the first woman in 1911, and in two separate categories), and Linus Pauling, among others. The Red Cross has snagged three. From a personal standpoint, the most obvious non-winner is Mahatma Gandhi, or as someone quipped, “Gandhi can do without a Nobel Prize, but can the Nobel Committee do without Gandhi?”

I think not.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].