By Jim O’Neal

Today’s occasionally frenetic journalism began during the Civil War, for two basic reasons.

The first was the telegraph, since this was the first instant-news war in history, and the issue was much like we have with today’s internet. Reports could be filed almost immediately and it resulted in a mad rush to be first with “breaking news.”

The other was steam, used for steam-powered locomotives and the relatively new steam-powered printing presses. Reporters could hop on a train and return to their offices quickly if a telegraph office wasn’t handy. Either way, the demand for timely and accurate news from the front lines transformed American journalism. It was a culture of “Telegraph all the news you can get, and when there is no news, send the rumors.”

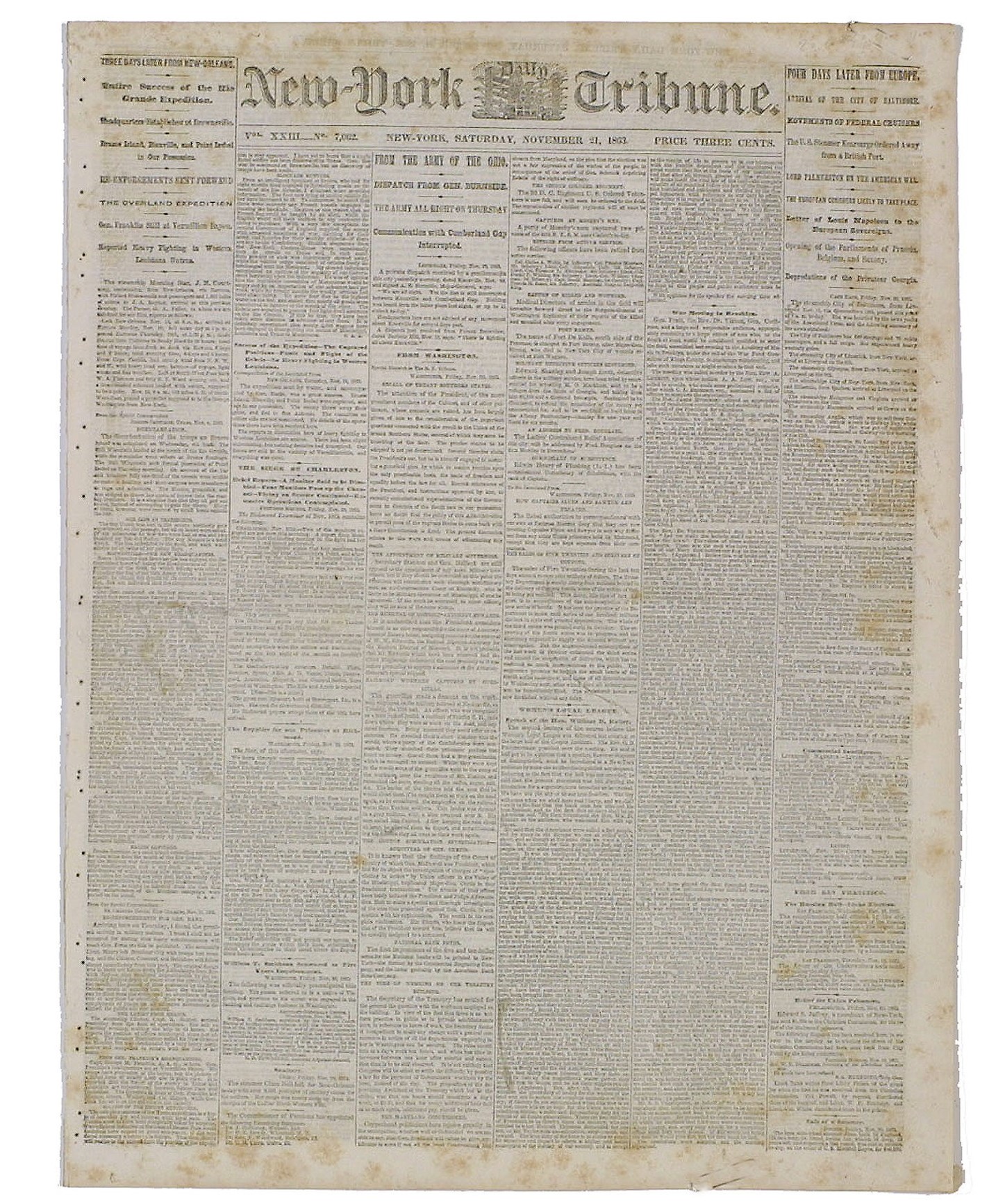

They did a lot of that, and the competition was ferocious. New York had 18 daily newspapers, with four or five focused on the war – including the New York Tribune (Horace Greeley), The New York Herald (James Gordon Bennett), and The New York Times (Henry J. Raymond). Of the three, Greeley was the acknowledged celebrity and well-known for his erratic views as opposed to straight news.

He would later challenge President Grant’s reelection in 1872 by splitting the Republican Party, which resulted in the Democrats cancelling their convention and throwing their support to Greeley. So it was Republican Grant against Liberal Republican Greeley … and no Democrats. Grant won easily and Greeley died before the Electoral College could vote (Greeley actually received three posthumous electoral votes).

Bennett may have been the first great genius in American journalism. He had migrated from Scotland after being trained as a Catholic priest, had the finest education, and was devoted to a balanced approach to the news. However, even he occasionally fell victim to rushing to print too fast.

An interesting feature of the “war newspapers” was that each copy was handed around and read by dozens of people. Another is that the armies – both sides – did not report casualties. There were no official lists of those killed, captured or wounded. This was done by individual reporters, who compiled lists and published them. This enhanced reader interest immensely when a reporter was covering specific units where loved ones were involved.

As a group, Civil War correspondents were a motley group of ruffians who called themselves the “Bohemian Brigade.” There was lots of criticism, particularly of The New York Herald, for sending out these hard-drinking characters into the field. Even so, simply substitute today’s gossipy and irresponsible websites for the Civil War telegraph and it becomes perfectly clear how little reporting the news has changed in 150 years.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].