By Jim O’Neal

The Gilded Age was an exciting time in American history and roughly spans the period following the Civil War and extending to the start of the 19th century. The powerful combination of technical advances in manufacturing, communications and transportation marked the transformation of America from an agrarian society to a major industrial pioneer.

In the brief time between 1870 and the beginning of the first World War in Europe, the American economy grew faster, became more diversified and changed more profoundly than at any earlier 50-year period in the nation’s history. In the process, the United States created the largest and most modern industrial economy on earth. In 1890, the Census Bureau declared that the frontier, a hallmark of “The American Story,” had quietly ceased to exist. Newspaperman Horace Greeley’s advice to “Go West, young man” had become apocryphal.

However, it is still possible to trace the roots back to 1830, when men with vision and courage began pushing the fantastical idea that railroads (which barely existed) should be flung across the entire American continent. President Lincoln, agile enough to plan on how to win a war and also consider the nation’s future, was a railroad supporter. In 1862 he had the Pacific Railway Act attached to the important Homestead Act. Two companies, one in the San Francisco area and one in the East, started laying tracks.

On May 10, 1869, they met in Utah and celebrated by driving a golden spike. A telegraph was sent to both coasts with a single word: “DONE!” By 1876 it took just 88 hours and 33 minutes to travel from San Francisco to New York City. Also on board was the United States mail (the telegraph had killed the Pony Express 10 years earlier), fresh vegetables, real beef instead of bison, and gold deposits. Businessmen used it to cut down on travel time, and pioneers abandoned their prairie schooners.

Cities flourished as the rapid growth of factories accelerated urbanization and waves of migrants were attracted to the promise of better jobs. As America raced to become the largest economy, by the 1870s it became clear what was needed most: light. Light for the factories now running 24 hours a day. Light for the streets and homes and even for the library where people congregated to improve their English or hone their skills. The problem was how to get it. Whale oil was out, kerosene too smoky and gaslight too dim and dangerous. The magic elixir was electricity! It had been known since Ben Franklin and had been appropriated to invent the telegraph, telephone and phonograph – three world-changing devices in which Thomas Edison had played a role.

In April 1881, Scientific American dedicated an issue to the enhancement of electricity. On the cover was a sketch of the lights on NYC sidewalks. Seeing the cityscape glow with faces and objects at night suggested a new immense opportunity. Broadway owed the credit to a young inventor from Cleveland named Charles Brush. For a brief time, Brush’s system dominated the field. Not surprisingly, Edison – aka “The Wizard of Menlo Park” – would overtake him.

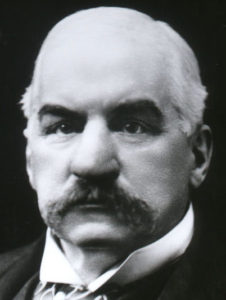

On New Year’s Eve 1879, using 1 million lightbulbs, there was a demonstration of what would become “The Great White Way.” The Wizard, always looking to the future, thought of the superb potential for expansion, and soon Hollywood was involved and Edison invented moving pictures. In time he would boldly predict, “We will make electricity so cheap that only the rich will burn candles.” And so it was with oil, transportation, publishing, retail and steel. When Andrew Carnegie sold his steel interests to J.P Morgan for $480 million ($300 billion today), it was the largest personal sale in world history.

In 1873, a few years before we met Tom Sawyer, Mark Twain published his novel The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today. He had spotted the irony of the situation and how the splendor of a gold patina was masking the workers’ low wages and the dangerous and unhealthy conditions – a glittering surface obscuring the corruption underneath.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].