By Jim O’Neal

“Go West, young man, go west and grow up with the country.”

This widely known quote is directly associated with the concept of Manifest Destiny, as Americans inexorably expanded from being huddled along the Atlantic Ocean, across a vast continent, to the shores of the magnificent Pacific Ocean. What is less agreed is the source of this exuberant exhortation. A vast majority attribute it to a man who could easily be crowned the Nation’s Newsman: Horace Greeley. However, there is no definitive evidence in any of his prolific writing or plethora of speeches.

By 1831, a young (age 20) Horace Greeley arrived in New York, devoid of most things, especially money, except for a burning desire to exploit his skills as a journeyman printer. The following year, his reputation was rapidly expanding, having set up a press to publish his modest first newspaper. At 23, he had a literary weekly and a relationship with the great James Gordon Bennett, founder of the New York Herald. The future beckoned the aspiring writer-orator to bring his encyclopedic skills to the masses in new and exciting ways.

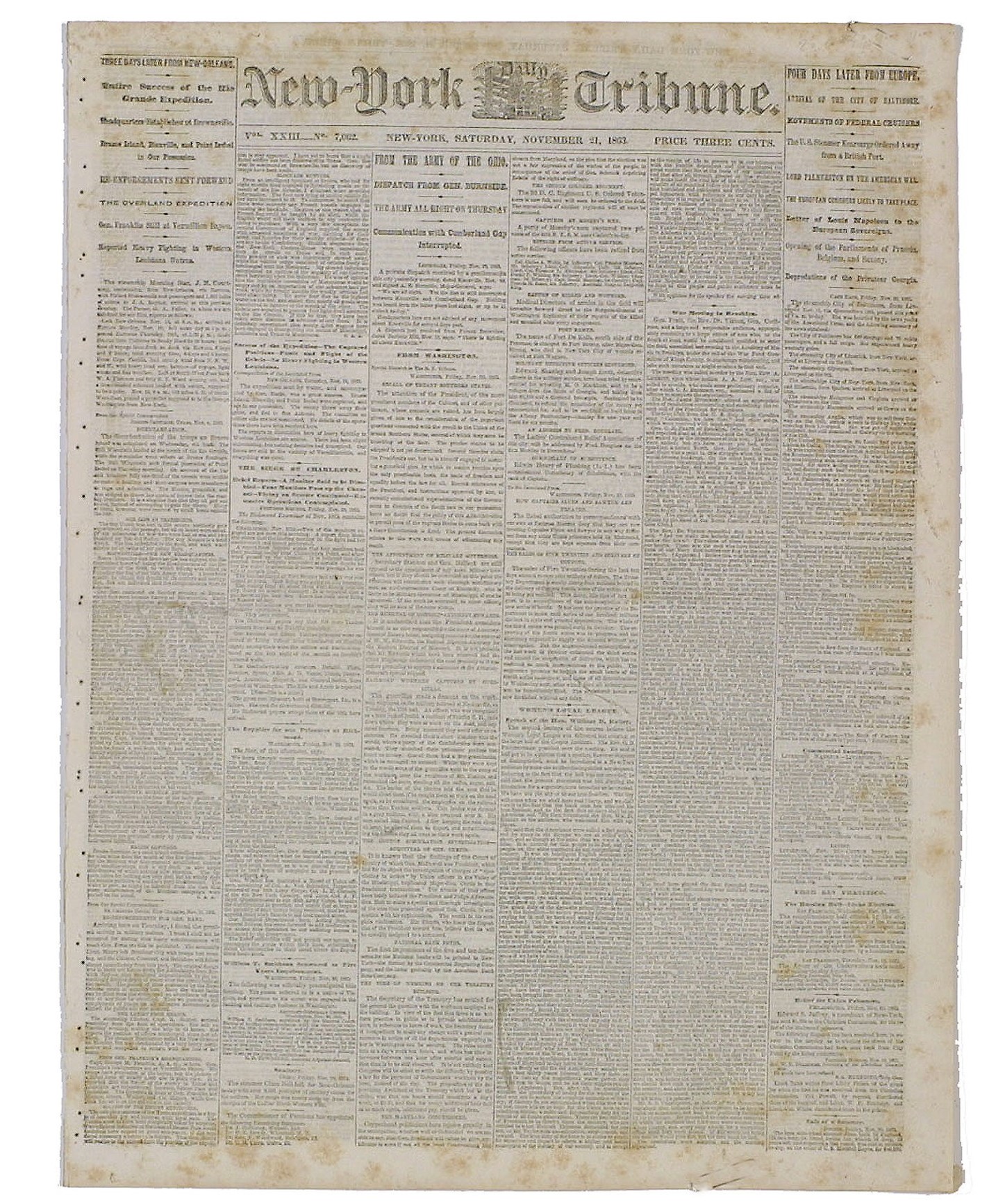

Inevitably, using borrowed money, he started the New-York Tribune, publishing the first issue on April 10, 1841. Perhaps by coincidence or divine intervention, this was the same day New York City hosted a parade in honor of recently deceased President William Henry Harrison (“Tippecanoe and Tyler Too”), who had died on April 4. Harrison, the ninth president, had only served from March 4, the shortest tenure of any U.S. president.

The 68-year-old William Henry Harrison was the oldest president to be inaugurated until Ronald Reagan was elected in 1980 at age 69 (both were young compared to the current president and president-elect). In this situation, Harrison had given a lengthy two-hour inaugural address (8,445 words – even after Daniel Webster had edited out almost half), opted not to wear a coat to demonstrate his strength, caught pneumonia and died four weeks later. His wife Anna was at home also sick and, in a first, Congress awarded her a pension – a one-time payment of $25,000 equal to the president’s salary. Their grandson – Benjamin Harrison – would become the 23rd president in 1889.

The new Greeley newspaper was a mass-circulation publication with a distinctive tone reflecting Greeley’s personal emphasis on civic rectitude and moral persuasion. Despite the challenging competition of 47 other newspapers – 11 of them dailies – the Tribune was a spectacular success. Greeley quickly became the most influential newspaperman of his time. From his pen flowed a torrent of articles, essays and books. From his mouth an almost equal amount. In the process, he revolutionized the conception of newspapers in form and content, literally creating modern journalism.

Then with the advent of steam-powered printing presses and a precipitous drop in prices from 6 cents to a penny, more people were clamoring for more news. The common man, ever eager for more information in any category, began to read about the financial markets and almost everything about everyone.

Greeley was intensely interested in Western emigration and encouraged others to take advantage of the opportunities he envisioned. “I hold that tens of thousands, who are now barely holding on at the East, might thus place themselves on the high road to competence and ultimate independence at the West.” Curiously, he made only one trip west, going to Colorado in 1859 during the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush, joining an estimated 100,000 gold-seekers in one of the greatest rushes in the history of North America. The participants, logically dubbed the “Fifty-Niners,” found enough gold and silver to compel Congress to authorize a Mint in 1862. The new Denver mint was opened in 1906.

Greeley developed a large group of followers who found in his raw eloquence and political fervor a refreshing perspective that fueled their appetite for more. For 40 years, Greeley was the busiest and boldest editor in America. Both men and women were attracted to his fiery perspective and guidance in all the great issues of the time. He spared no one, suffered no favorites and seemed to never let the nation or himself rest.

After becoming the first president of the New York Printers’ Union, he led the fight for distribution of public land to the needy and poor. He was a fierce advocate for government rescues during times of social issues, a new role for officeholders and the sovereign state as well. Others have remarked on the similarities between the 1837 depression and FDR’s New Deal response a century in the future. Still others consider him a trust buster, but 60 years before Teddy Roosevelt and his Big Stick threats.

Perhaps less skilled in the art of personal introspective, Greeley viewed himself as an “indispensable figure in achieving national consensus.” His lofty goal was nothing less than the eradication of political differences and a complete embrace of Whig principles and sensibilities. (We are still waiting for his version of transcendental harmony.) Alas, his yearning for consensus blunted his understanding of political events. He was surprisingly slow to grasp the moral dimension of slavery until the 1850s when violence erupted (i.e. Bleeding Kansas).

He abandoned his dream of consensus in favor of the North’s overwhelming strength to simply impose its will, saying “Let the erring states go in peace.” He then turned to badgering President Lincoln to negotiate a peace to stop the bloodshed – basically preserving slavery. Lincoln’s letter to the editor on Aug. 22, 1862, says it all: “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that.” The subtle wisdom not to expand the war into any of the border states is a point often overlooked.

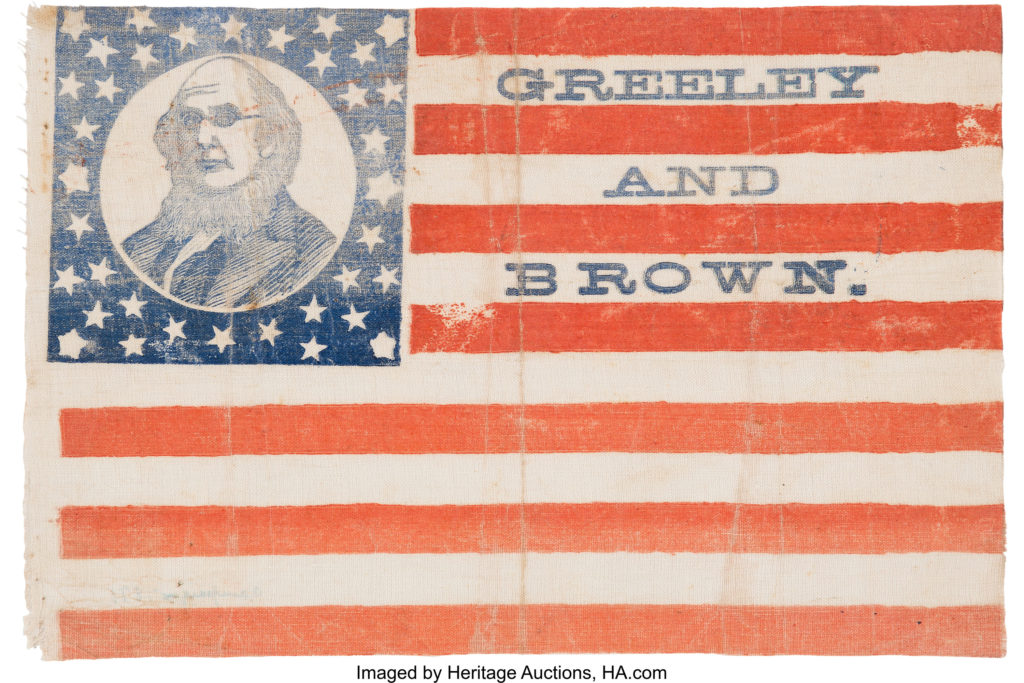

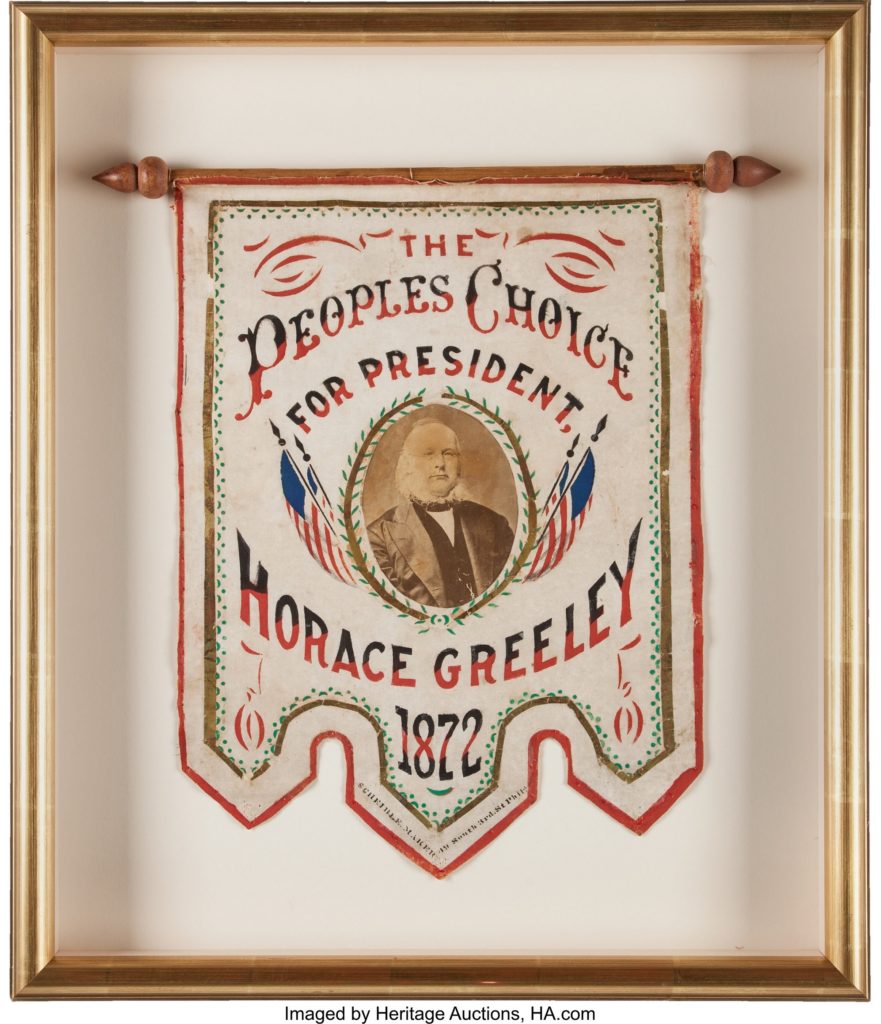

In 1872, the famously eccentric editor from New York ran for president against Ulysses S. Grant, lost badly, and then died before the electoral votes were counted. Lincoln had likened Greeley to an “old shoe — good for nothing now, whatever he has been,” and Greeley himself perceived his failure. “I stand naked before my God, the most utterly, hopelessly wretched and undone of all who ever lived.”

Personally, I think not. (Seek thee proof … simply look around us today.)

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].