By Jim O’Neal

In his autobiography, Horace Greeley made a critical observation when he wrote: “Having loved and devoured newspapers, I early resolved to be a printer if I could.” Not only was he able to fulfill his resolution, but a strong case exists that he was probably the preeminent printer/editor of the 18th century, easily surpassing Ben Franklin, James Gordon Bennett and the other prominent American editors.

Newspapers had started as a modest sideline for printers before they evolved into a potent force leading the inexorable push in support of American independence. It is telling that the founders, who debated for months over the construction of the Constitution and made many compromises in the process, easily agreed on the value of a free and independent press. The very first Amendment to this sacred document guaranteed freedom of the press and it is still the first one to be defended yet today without any controversy. In addition, the Postal Service Act of 1792 established generous subsidies to ensure widespread circulation (under the law, a newspaper was delivered to subscribers for only 1 penny up to 100 miles away).

As a child, Greeley (1811-1872) demonstrated a remarkable affinity for the printed word. He learned to read by age 3, and polished off the entire Bible two years later before starting on John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress – a Christian allegory (1678) cited as the first novel written in English. This purportedly was followed by the Arabian Nights.

He had an encyclopedic memory crammed with dates, facts and significant events. Children with these mental abilities typically had little time for physical ability and Greeley was no exception. He was of little use in planting crops, tending animals or simply cavorting with other children. However, he was so obviously intelligent that a wealthy neighbor offered to send him to the prestigious Phillips Exeter Academy and then on to college. The Greeley family refused to accept any form of charity and Horace became even more determined to be successful.

In 1826, he accepted a position as a printer’s apprentice and in his spare time he read his way through the town’s public library. By 1831, he had migrated to New York City, trying his hand at various jobs involving printing, but with only modest success. Within three years, he was able to publish the first issue of The New-Yorker, an inexpensive literary magazine that failed during the Panic of 1837.

Undaunted, in 1840 he borrowed $1,000 and with the remnants of The New-Yorker started the now famous New-York Tribune. His timing was perfect and the Tribune was a success nearly from the first issue. Greeley had developed a revolutionary credo that was quickly adopted by the masses … the simple premise that newspapers should be printed to both entertain and inform the entire community. His competition had adopted a style that was limited to narrow petty issues, private interests and too many advertisements for shady schemes.

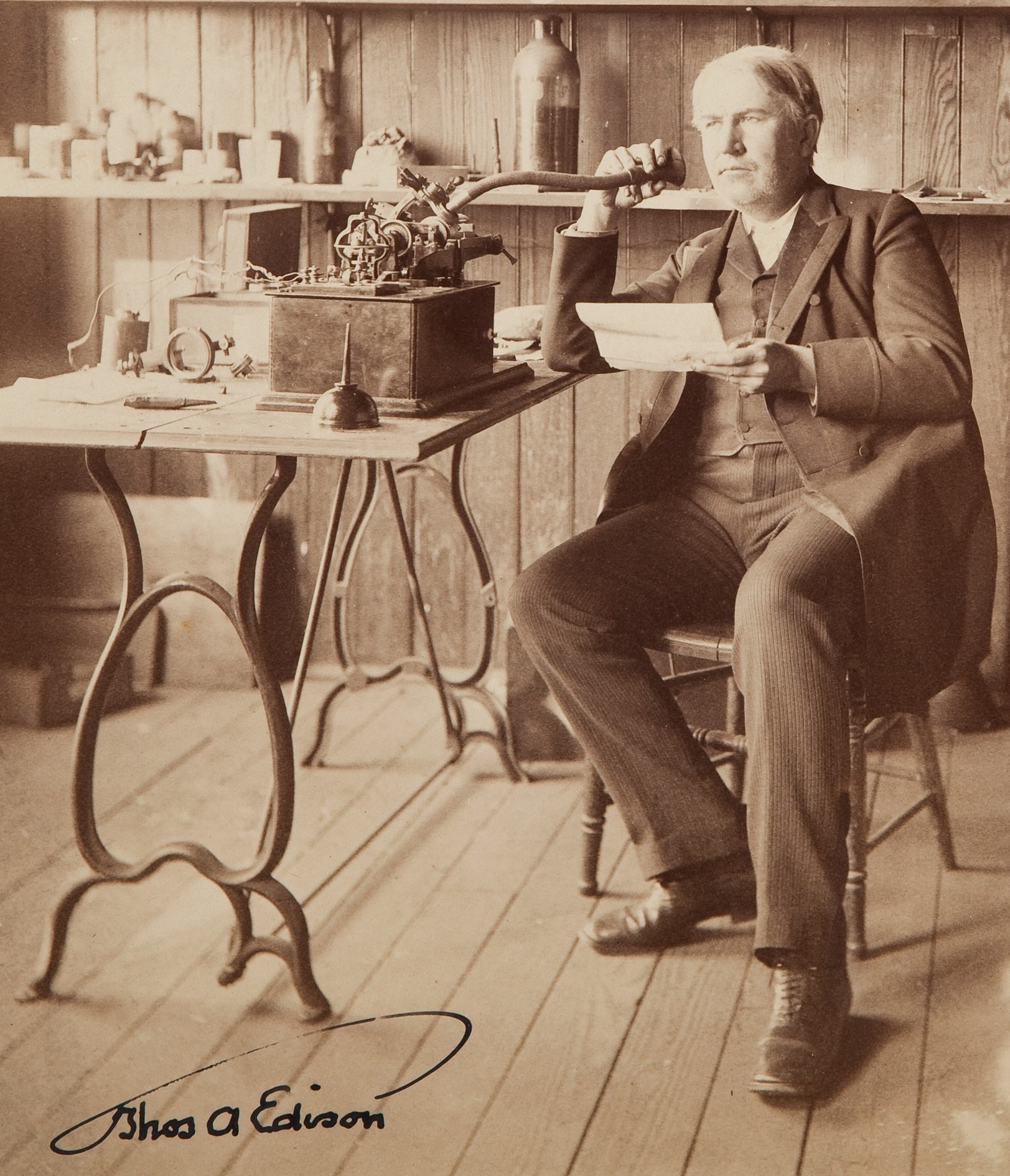

Greeley’s success as a publisher was primarily due to his bold thinking, daring imagination and total rejection of the stifling precedent that was so common. He literally invented the modern-style newspaper, much as Thomas Edison invented the light bulb. Those countless hours of reading had given him a discriminating taste and an eye for superior printing that hadn’t existed.

For three decades in the middle of the 19th century (1840-70), his pen produced a virtual torrent of essays, articles and books that earned him a reputation as a highly respected printer/editor in the newspaper vortex of New York. Inevitably, politics became his area of expertise, altering the form and content in new and exciting ways. Many believe he personally created modern journalism, proclaiming, “He chases rascals, not dollars.”

He was described as having a weird appearance … tall and angular with a head, torso and limbs that didn’t match. This was a perfect match for the range of topics he eagerly promoted: socialism (hiring Karl Marx to extoll the virtues), vegetarianism, agrarianism, feminism (he supported black suffrage but not for women), temperance and anti-trust (60 years before Teddy Roosevelt). He was anti-slavery but not for abolition, and was willing to let slave states secede at will (they will come back … no need for war).

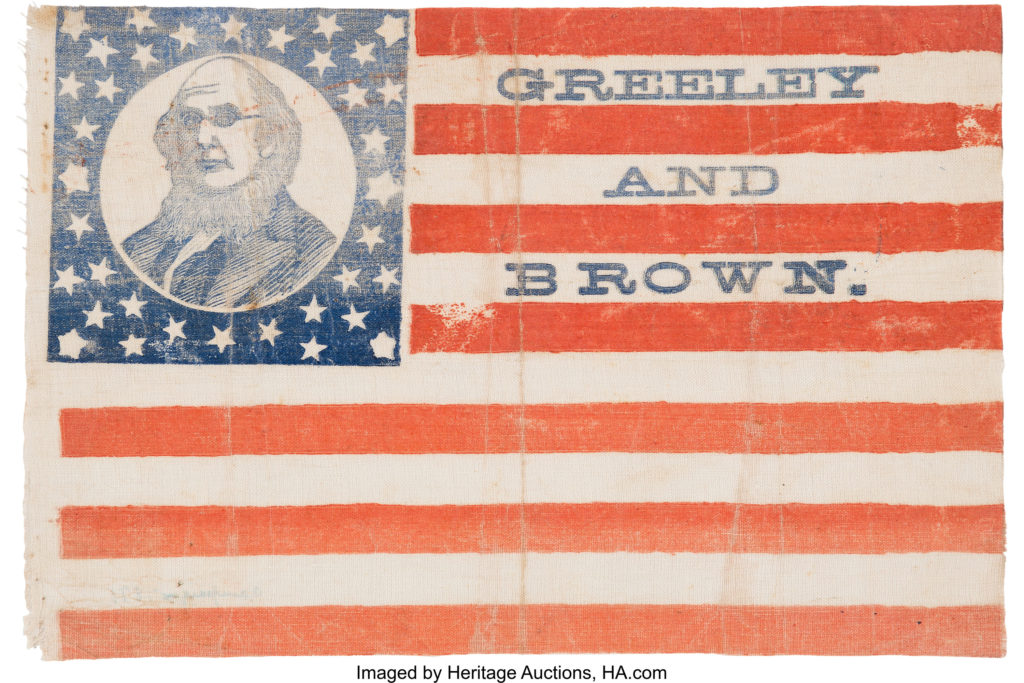

This whole story came to an end in 1872 when he felt compelled to challenge President Ulysses S. Grant. Despite being one of the founders of the Republican Party, he had exposed a devastating list of crimes, corruption and incompetence that Grant had to be held accountable for. In a twist, the Democrats – who didn’t have their own candidate – nominated Greeley as a Liberal Republican!

Greeley died 30 days before the election and Grant had a reasonable second term.

Our country was a better place because of Horace Greeley.

This strange-appearing man – who managed to make Abraham Lincoln look debonair, who was too frightened to play baseball, yet who had the temerity to mingle with frenzied crowds taunting him after he paid the bail for Jefferson Davis after the Civil War – set a standard for personal ethics that still stands, although lost in the mist of history.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].