By Jim O’Neal

On Jan. 31, 1917, the German Secretary of State for the Imperial Navy addressed the nation’s parliament. “They will not come because our submarines will sink them.” He went on to state, categorically, “Thus, America, from a military point of view, means nothing … nothing!”

Strictly from an Army standpoint, Eduard von Capelle may have had a point. The U.S. Army had gradually declined in size to 107,641 – ranked No. 17 in the world. Additionally, the Army had not been involved in large-scale operations since the Civil War ended in 1865, over 50 years earlier.

The National Guard was marginally larger, with a total of 132,000. However, these were only part-time militia spread among the 48 states and they, quite naturally, varied considerably in readiness. Equipment was another issue since they were armed with nothing heavier than machineguns. This was rectified significantly in 1917-18 when 20 million men were registered for military service.

Known to only a few, two weeks earlier on Jan. 16, British code-breakers had intercepted a diplomatic message sent by German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann. The “Zimmermann Telegram,” as it is known, was intended for Heinrich von Eckardt, the German ambassador to Mexico.

The missive gave the ambassador a set of highly confidential instructions to propose a Mexican-German alliance should the United States enter the war against Germany. Von Eckardt was to offer the president of Mexico generous military and financial support if Mexico were to form an alliance with Germany. In exchange, Mexico would be free to annex the “lost territory in Texas, New Mexico and Arizona.” In addition to distracting the United States, Mexico could assist in persuading Japan to join in, as well.

At the start of World War I, Germany’s telegraph cables passing through the English Channel had been cut by a British ship. This forced the Germans to send messages via neutral countries. They had also convinced President Woodrow Wilson that keeping channels of communications open would help shorten the war. The United States agreed to pass on German diplomatic messages from Berlin to their U.S. Embassy in Washington, D.C.

The United States was still firmly committed to remaining neutral and not being entangled in foreign wars that did not pose a direct threat. Wilson had been re-elected in 1916 with a main slogan of “He kept us out of war!” But that did not prevent many individual citizens from joining and many were already fighting in the war in a variety of ways. Some had joined the British Army directly and others joined Canadians already in Europe.

There were also groups in the French Foreign Legion and a special group in the French Air Force. They formed the La Fayette Escadrille in honor of the Marquis de Lafayette, who was a friend from our own war for freedom. Lafayette had actually fought in the American Revolution as a major general under George Washington. He was even present at Yorktown, Va., when British Army General Charles Cornwallis had surrendered, effectively bringing an end to armed hostilities. When Lafayette died in 1834 in Paris, President Andrew Jackson had both Houses of Congress draped in black for 30 days. Individual members of congress also wore mourning badges. It is likely that we may have lost the war with Britain absent the help from the French.

Back on the morning of Jan. 17, 1917, one of the British codebreakers (Nigel de Grey) entered Room 40 of the British Admiralty and asked his boss a question: “Do you want to bring America into the war? I’ve got something that might do the trick!” It was a decoded copy of the Zimmermann Telegram.

Room 40 was the home of the British cryptographic center and they were acutely aware of the implications of disclosing their clandestine activities. They developed an elaborate plan to get a copy to President Wilson without exposing that they had been monitoring all transatlantic cables, including America’s (a practice that would continue for another 25 years). Wilson received a copy on Feb. 25 and by March 1, it was splashed on the front pages of newspapers nationwide.

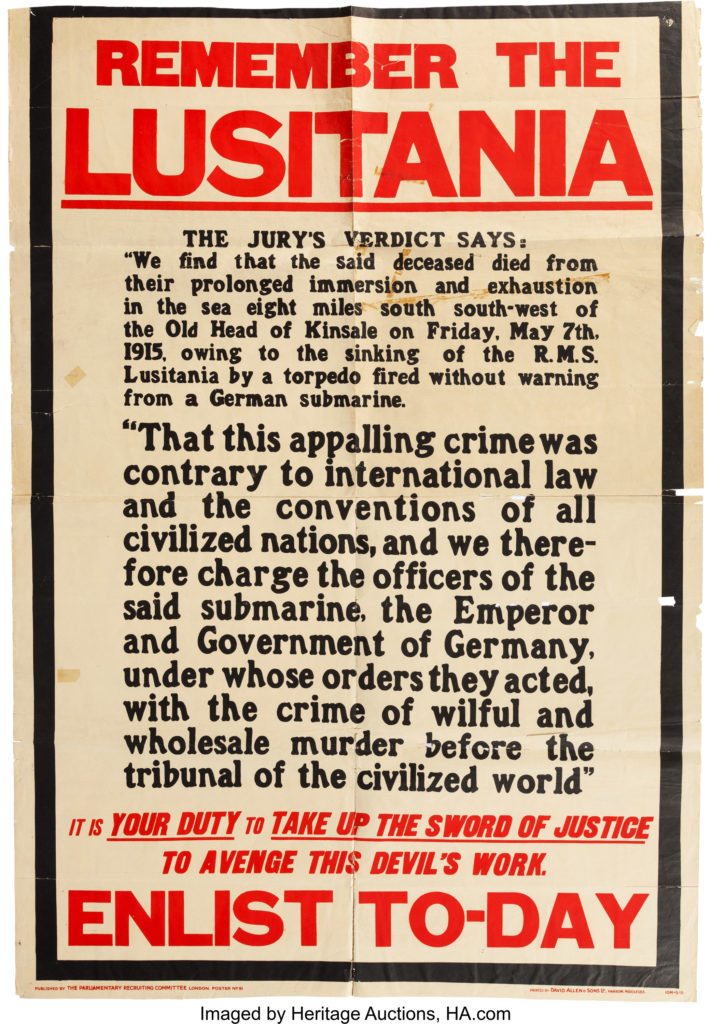

Diplomatic relations had already been severed with Germany in early February when Germany had resumed unrestricted submarine warfare on American ships in the Atlantic. The Zimmermann Telegram became the proverbial straw that broke America’s isolationism and on April 2, Wilson asked Congress to officially declare war, which they did four days later.

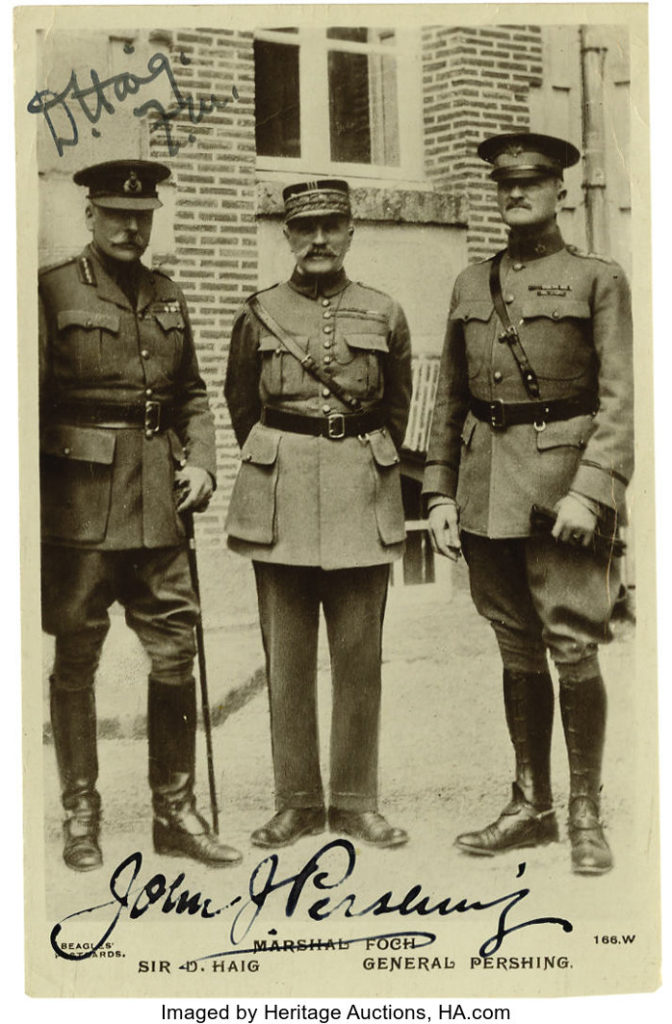

Remarkably, by June 17, the American Expeditionary Force had landed in France. General John J. Pershing and his troops soon marched on Paris. By 1918, it was almost as though Von Capelle’s prophetic “They will never come” had been trumped in six months by America’s melodramatic “Lafayette, we are here!”

Many of the best Room 40 personnel would end up at Bletchley Park to work on cracking the German Enigma machine. Their work is captured brilliantly in the 2014 film The Imitation Game, with Benedict Cumberbatch in the Oscar-nominated role of English mathematics genius Alan Turing.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].