By Jim O’Neal

It is mildly amusing to listen to members of Congress refer to the Founding Fathers whenever they’re trying to validate a political point or opinion (“That’s exactly what the framers intended when they wrote the Constitution!”). They seem to believe that our Founders held a Constitutional Convention (partially true), quickly hammered out a list of sacred provisions and then had each state ratify them en masse. Naturally, the real story is much more complicated and Constitutional scholars of today still debate various aspects of what is meant. Even the Supreme Court struggles to gain a consensus on “original intent.”

After the 13 American colonies tired of monarchical rule under King George III and Parliament, they decided to form an independent country. A committee was formed to start the ball rolling with a Declaration of Independence. Thomas Jefferson was formally elected to write the document and years later (1822), John Adams wrote a letter to Timothy Pickering explaining how Jefferson was selected: “First, he had a reputation for literature, science and a talent of composition. Though silent in Congress, he was prompt, frank, explicit and decisive upon committee and in conversation. He seized my heart and I gave him my vote. When he asked my reasons, I said – You are a Virginian and I am obnoxious and unpopular. Lastly, you can write 10 times better than I can!”

Following the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), the 13 original states ratified Articles of Confederation that served as the first Constitution. The primary principle of these articles was to preserve the sovereignty and independence of each individual state. A weak central government was formed, but great care was taken to ensure that it did not have any more power than previously assumed by the British King and Parliament. This issue of maintaining states’ rights would continue to perplex any efforts to federalize.

The states continued struggling under several different forms of Articles, Confederations and Conventions … all with loosely defined laws and regulations. Important issues like foreign policy, taxation, currency and basic commerce were hindered by competing state interests. Even the U.S. Army was under the direction of a Congress that was not well organized. These and other issues greatly worried the Founders, who believed the Union, as it existed in 1786, was in serious danger of breaking apart.

So it is true that we look to the Founding Fathers when we examine the great American experiment in democracy. But, the question remains: To whom did they turn for wisdom and guidance? Many found inspiration from Great Britain in the previous century, when the conflict between the King and Parliament escalated into a civil war. The generally Puritan Parliament simply moved to abolish the monarchy, executed Charles I in 1649 for treason and bravely established England’s first and only Republic. Oliver Cromwell became Lord Protector of England, Scotland and Wales. However, his death in 1658 created a power vacuum that was filled by Charles’ eldest son. So not much was really accomplished and they reverted back to a King + Parliament that ruled with deficiencies that continue to exist today.

Besides, it was now crystal clear that major changes were needed in America and, finally, a Constitutional Convention was scheduled for May-September 1787 in Philadelphia. It was described as an effort to revise the league of states and many state delegates arrived assuming the purpose was to debate and draft improvements. However, powerful voices were determined to forge a powerful new national government. Among this group were James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, who intended to create a new government rather than tinker with fixing the existing one.

After a long hot summer of debate, 39 of the original 55 delegates signed the new Constitution. It was released to the public to debate and gain state ratification. They immediately hit a snag over the absence of a Bill of Rights. There had been discussions among the delegates over the need for such a bill, but it was rejected by the Convention. The lack of a Bill of Rights became a rallying cry for the anti-federalists until advocates for the Constitution (led by James Madison) agreed to add one in the first session of Congress. Ratified on Dec. 15, 1791, the first 10 amendments – called the Bill of Rights – include sweeping restrictions on the federal government to protect rights and limit powers. Delaware was the first state to ratify the Constitution and the last was Rhode Island.

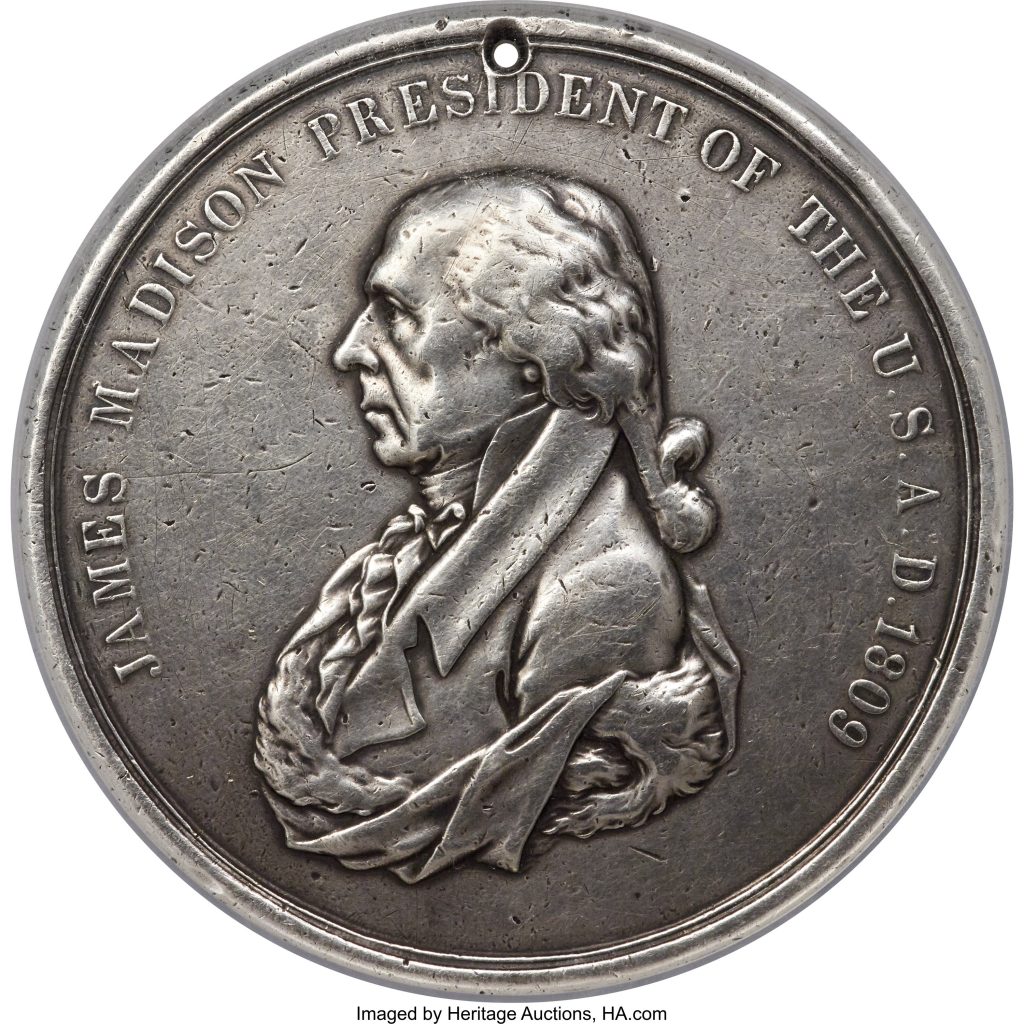

I am solidly in the camp of those who regard James Madison as Father of the U.S. Constitution. One does not need to look any further. No other delegate was better prepared for the Federal Convention of 1787 and no one contributed more in shaping the ideas of the document and explaining its meaning. He was a proponent for a consolidated, central republic to replace the loose and dysfunctional alliance under the Articles of Confederation. The Virginia Plan he brought to Philadelphia became the basis for the Convention agenda. His wish to clearly establish the sovereignty of the national government over the states has proven to be very durable. In 230 years, over 10,000 attempts have been made to amend it and as of now, only 27 have succeeded.

I rest my case.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].