“An army travels on its stomach.”

By Jim O’Neal

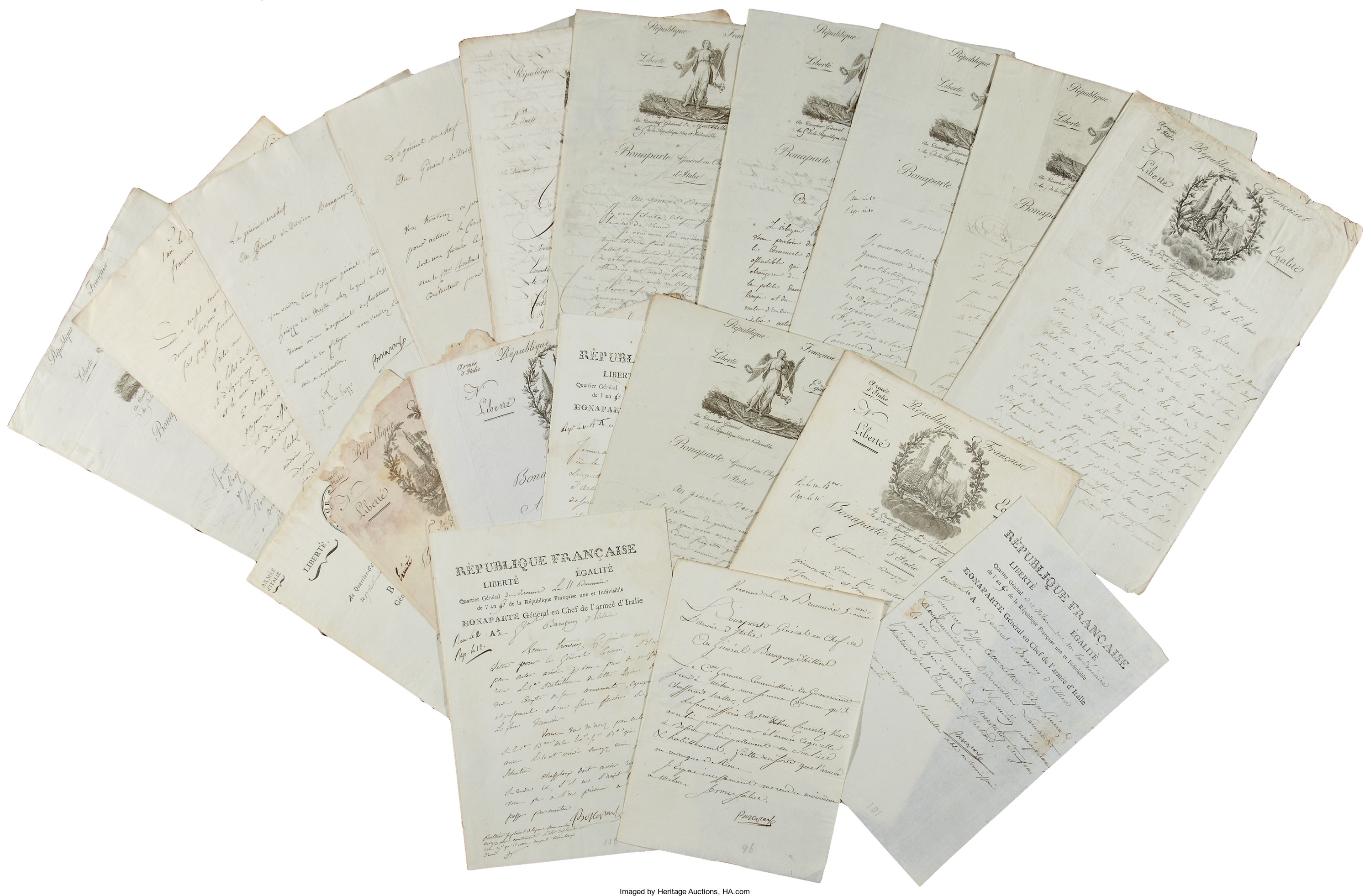

Both Frederick the Great and Napoleon Bonaparte are credited with aphorisms similar to this theme intended to emphasize the concept that a well-provisioned military is critical to its performance. In 1775, France offered 10,000 francs to anyone who could improve this persistent problem. In 1809, a confectioner named Nicolas Appert claimed the prize by inventing a heating, boiling and sealing system that preserved food similar to modern technology.

During the Revolutionary War, General Washington had to contend with this issue, as well as uniforms and ordnance (e.g. arms, powder and shot), which were essential to killing and capturing the British enemies. Responsibilities were far too dispersed and decision-making overly reliant on untrained personnel.

By the dawn of the War of 1812, the War Department convinced Congress that all these activities should be consolidated under experienced military personnel. On May 14, 1812, the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps was established. Over the past 200-plus years, 41 different men (mostly generals) have held the title of Army Chief of Ordnance. The system has evolved slowly and is regarded as a highly effective organization at the center of military actions in many parts of the world.

However, when the Civil War started in 1861, the man in charge was General James Wolfe Ripley (1794-1870), a hardheaded, overworked old veteran that Andrew Jackson had once threatened to hang for disobedience during the war with the Creek Indians. Ripley believed that the North would make this a short war and all they needed was an ample supply of orthodox weapons. He flatly refused to authorize the purchase of additional rifle-muskets for the infantry; primarily because of a large inventory of smooth bore muskets in various U.S. ordnance centers. Furthermore, he adamantly refused to allow the introduction of the more modern breech-loading repeating rifles due to a bizarre belief that ammunition would be wasted.

After two years of defiantly resisting the acquisition of new, modern weaponry, he was forced to retire. He was derided by the press as an old foggy, while some military historians claim he was personally responsible for extending the war by two years – a staggering indictment of enormous significance if in fact true!

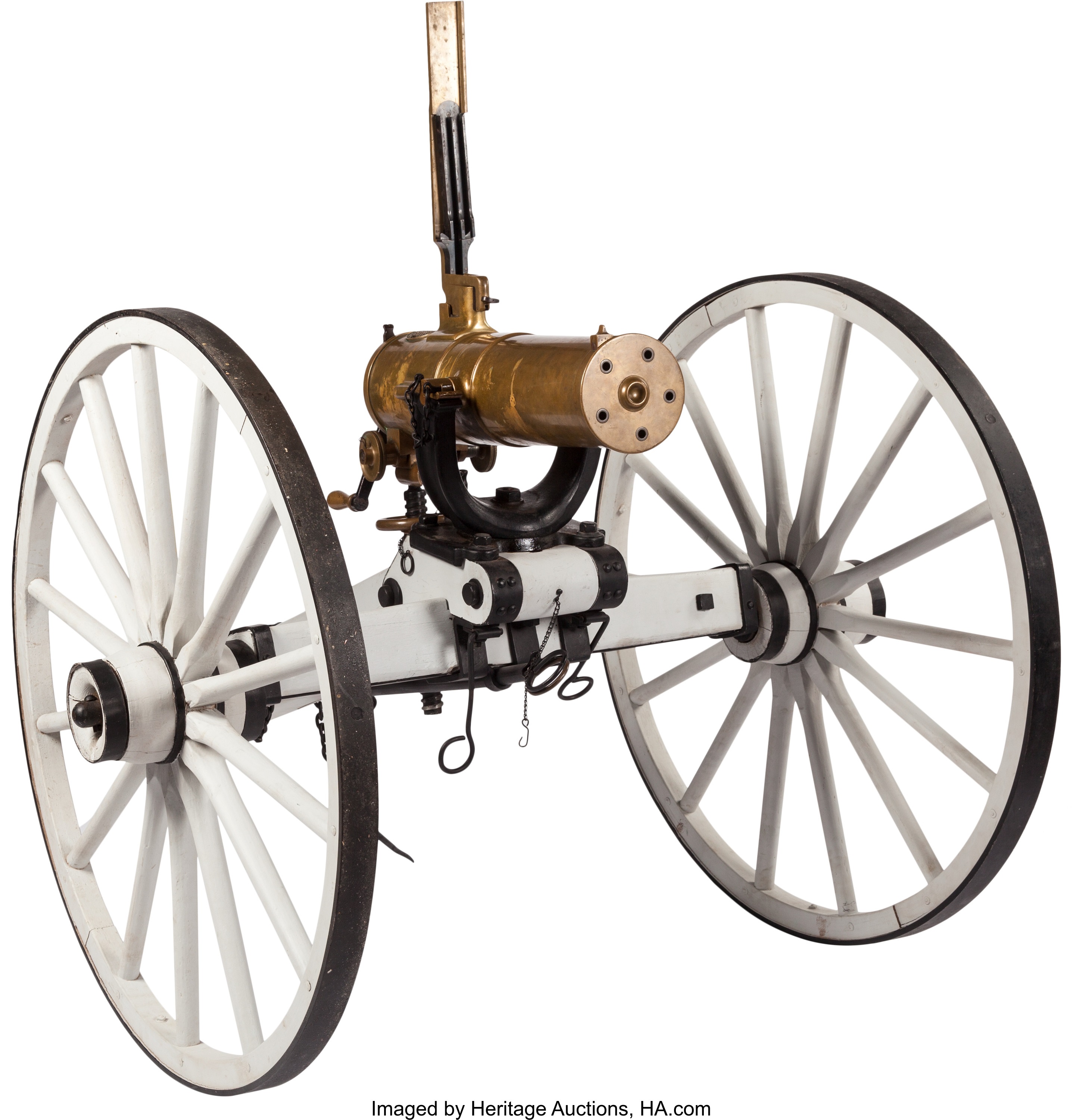

One prominent example occurred in early June 1861 when President Lincoln met the first-known salesman of machine guns: J.D. Mills of New York, who performed a demonstration in the loft of a carriage shop near the Willard Hotel. Lincoln was so impressed that a second demonstration was held for the president, five generals and three Cabinet members. The generals were equally impressed and ready to place an order on the spot. But, Ripley stubbornly managed to delay any action.

Lincoln was also stubborn and personally ordered 10 guns from Mills for $1,300 each without consulting anyone. It was the first machine gun order in history.

Then, on Dec. 18, 1861, General George McClellan bought 50 of the guns on a cost-plus basis for $750 each. Two weeks later, a pair of these guns debuted in the field under Colonel John Geary, a veteran of the Mexican War, the first mayor of San Francisco and, later, governor of both Kansas and Pennsylvania. Surprisingly, he wrote a letter saying they were “inefficient and unsafe to the operators.” But the colorful explorer General John C. Fremont, who commanded in West Virginia, sent an urgent dispatch to Ripley demanding 16 of the new machine guns.

Ripley characteristically replied:

“Have no Union Repeating Guns on hand and am not aware that any have been ordered.”

After several other tests produced mixed results, Scientific American wrote a requiem for the weapon, saying, “They had proved to be of no practical value to the Army of the Potomac and are now laid up in a storehouse in Washington.”

Then, belatedly, came a gifted inventor, Richard J. Gatling, who patented a six-barrel machine gun on Nov. 4, 1862. Gatling tried to interest Lincoln, who had now turned to other new weapons. However, some managed to get into service and three were used to help guard The New York Times building in the draft riots of July 1863. The guns eventually made Gatling rich and famous, but it was more than a year after the end of the war – Aug. 14, 1866 – when the U.S. Army became the first to adopt a machine gun … Gatlings!

It is always fun to consider counterfactuals (i.e. expressing what might have happened under different circumstances). In this case, if Andrew Jackson had hanged Ripley, then the North would have had vastly superior weaponry – especially the machine gun – and the war would have ended two years earlier. Many battles would have been avoided … Gettysburg … Sherman’s March to the Sea. Lincoln would have made a quick peace, thereby avoiding the assassination on April 14, 1865.

If … if … if …

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].