By Jim O’Neal

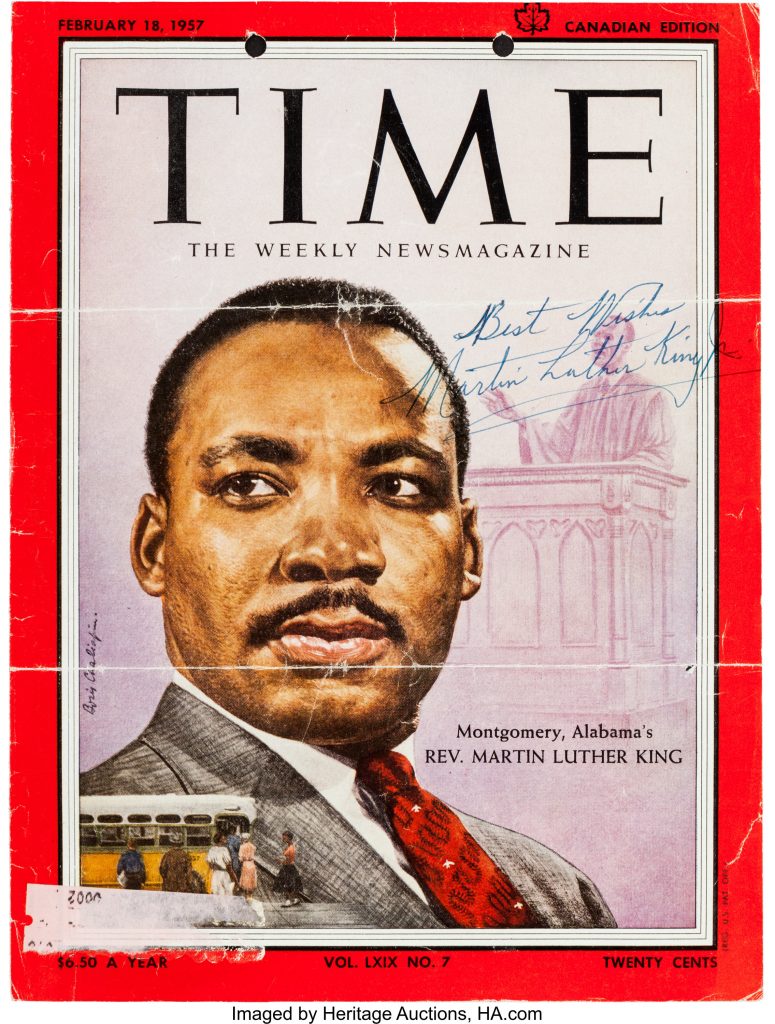

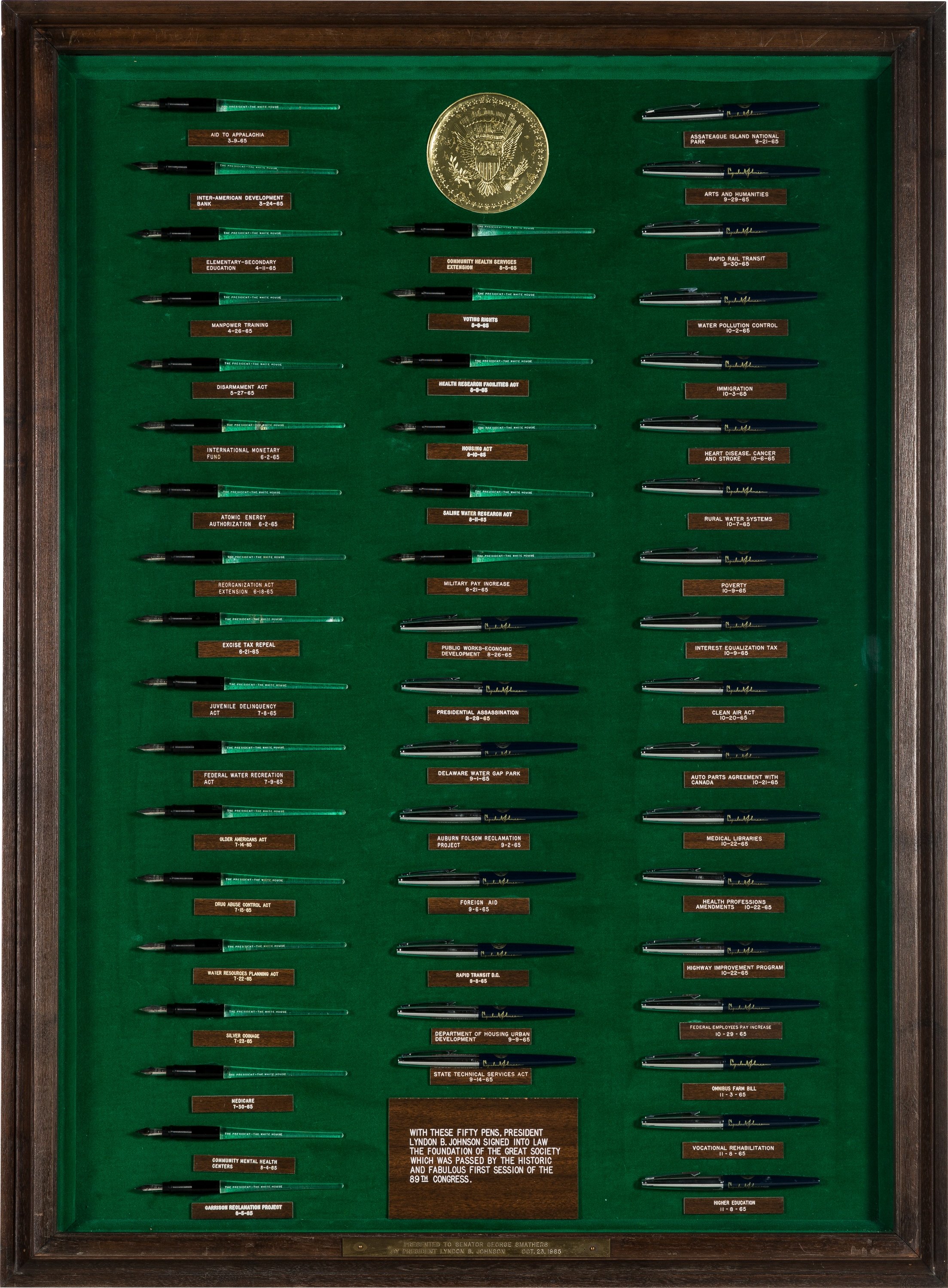

In 1964, Martin Luther King Jr. was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. He was on a mission that would include a march over a bridge in Selma, Ala., and he led a high-profile protest over voter-registration rules. Congress finally passed the Voting Rights Act, but it would turn out to be too late. King’s ideas about non-violence were poised for a rapid decline. The long-overdue legislation simply provoked an expression of rage, repression and frustration. Soon, riots broke out in Watts, followed by San Diego, Chicago, Philadelphia and Springfield.

The message seemed clear. This violence was not targeted against unfair laws, long-denied rights or even a new brand of segregation. It was against class distinctions and the invisible racism that deprives people of good jobs and better housing. The struggle to eat at the same lunch counters, and use the same restrooms, hotels or drinking fountains was over. This was about economic inequalities and disparities in everyday life. The voices that were speaking louder than MLK reflected the speeches of Malcolm X … belief in the purity and pride of the black race and separation from whites to obtain true freedom and self-respect.

The fever fueled urban rioting like a contagion, even after Malcolm was killed by a rival black Muslim in 1965. Eight thousand deaths or injuries occurred in 100 U.S. cities from 1965 to 1968. Malcolm’s provocative separatist ideology morphed into the hands of Stokely Carmichael and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, along with the Black Power sloganeering of Bobby Seale and the Black Panthers. Despite the efforts of broad swathes of committed people, there was a pervasive, ominous fear of a racial clash that was lurking in the shadows, ready to pounce.

In America, most years are routine… 365 days filled with weeks and months and only occasionally an event that might change the arc of history. Rarely do we experience shocks to the system that put us in a new orbit. Ironically, we’re in a classic worldwide disruption now and the path back to normalcy is filled with uncertainty. Even more critical is the simple fact that virtually everyone on this tiny speck has to join in or we all might perish. The pandemic is just one of the dangers. Climate change is a global concern and we’re also drifting back toward another Cold War with obvious parallels to the past. Nobody expected the events in 1914 to expand into a world war, yet almost everyone could see how WW2 was bound to occur.

And thus it was in 1968 when we endured a very bumpy ride.

Perhaps it began on Jan. 30 of that year when North Vietnam launched the Tet Offensive and caught everyone on our side flat-footed. A surprise attack on 100 cities was just implausible, but it did happen. Eventually, the military regained control, but in the process surrendered an enormous strategic PR advantage to the enemy. The American government had been promising that “Victory is in sight,” but was forced to retract the assertion. Walter Cronkite – the most trusted man in America – declared, “The Vietnam War is mired in a stalemate.” President Johnson took it one step further: “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost the American people.”

This public embarrassment was followed by the astonishing Kerner Commission report in February. Established by the president, the blue-ribbon group was charged with investigating the causes of the rash of riots sweeping American cities. In a stinging rebuke, it blamed the riots on police brutality, racism and lack of economic opportunities. In siding with the rioters, the 468-page bestseller concluded with a bombshell: “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one white – separate and unequal.” It charged that white society is clearly implicated in the ghetto – “White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it and white society condones it.”

President Johnson promptly ignored it.

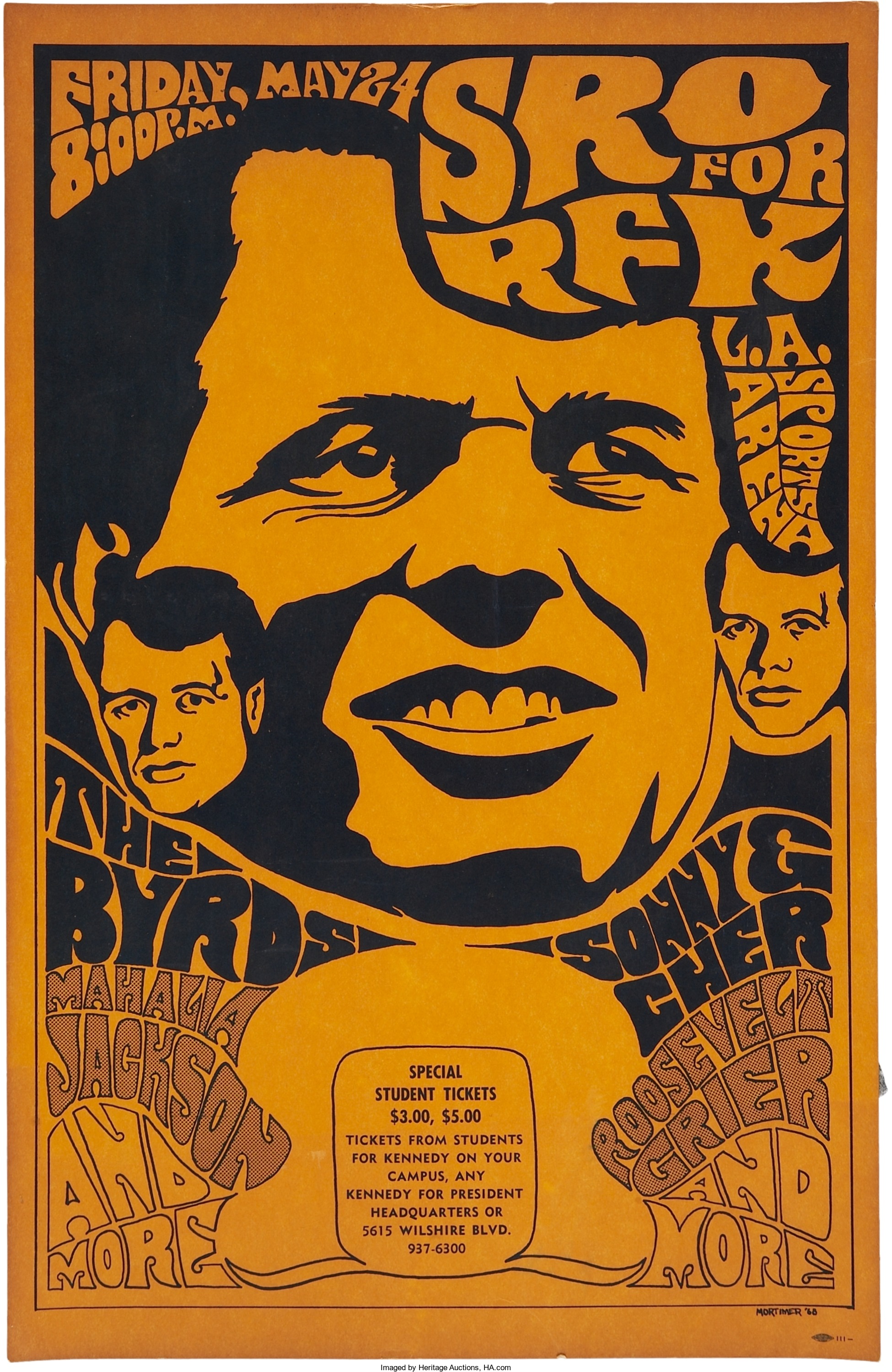

As the 1968 presidential primary season rolled around, Tet gave a boost to long-shot Eugene McCarthy. Running as a one-issue candidate (the war), he snagged a surprising 42% of the New Hampshire primary. Enter Bobby Kennedy, who, like most of America, was undergoing a transformation over Vietnam, civil rights and the charge America was not a moral country. However, he clung to the belief that not having a Kennedy in the White House was the missing elixir. He announced his candidacy on March 16.

Two weeks later (March 31), President Johnson made a prime-time speech to the American people. After listing the many positive things that had been accomplished, he started talking about a growing division in America and asked everyone to guard against divisiveness and its ugly consequences. He closed by saying he couldn’t afford to waste any of his precious time on partisan politics and … “I shall not seek and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your president.”

It had a somber, even sad tonality that when read today doesn’t seem to fit together.

Four days later, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis and the now-familiar bright orange flames flared over Harlem, Chicago, Detroit and Kansas City. People were losing faith in our institutions and wondering who to blame.

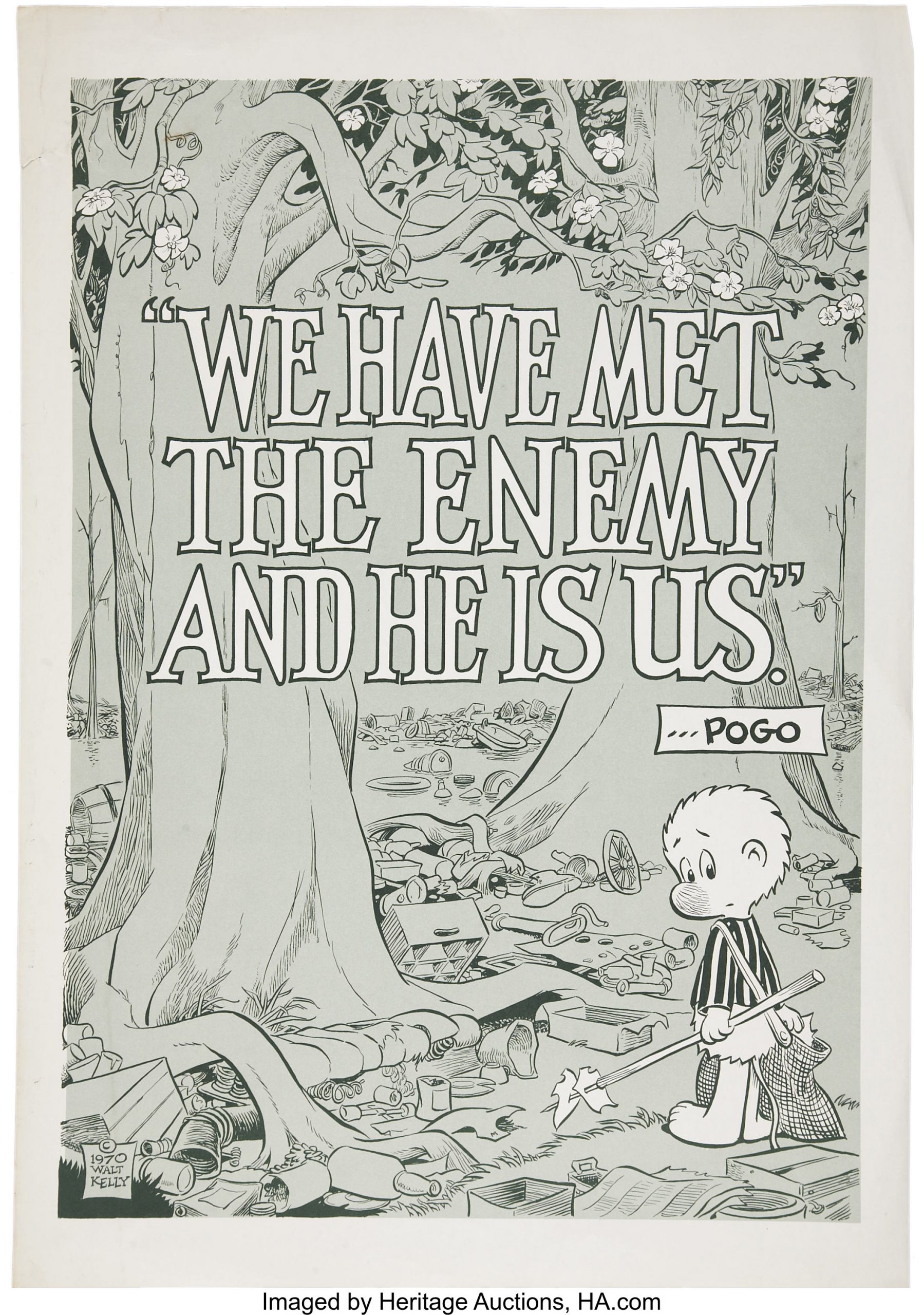

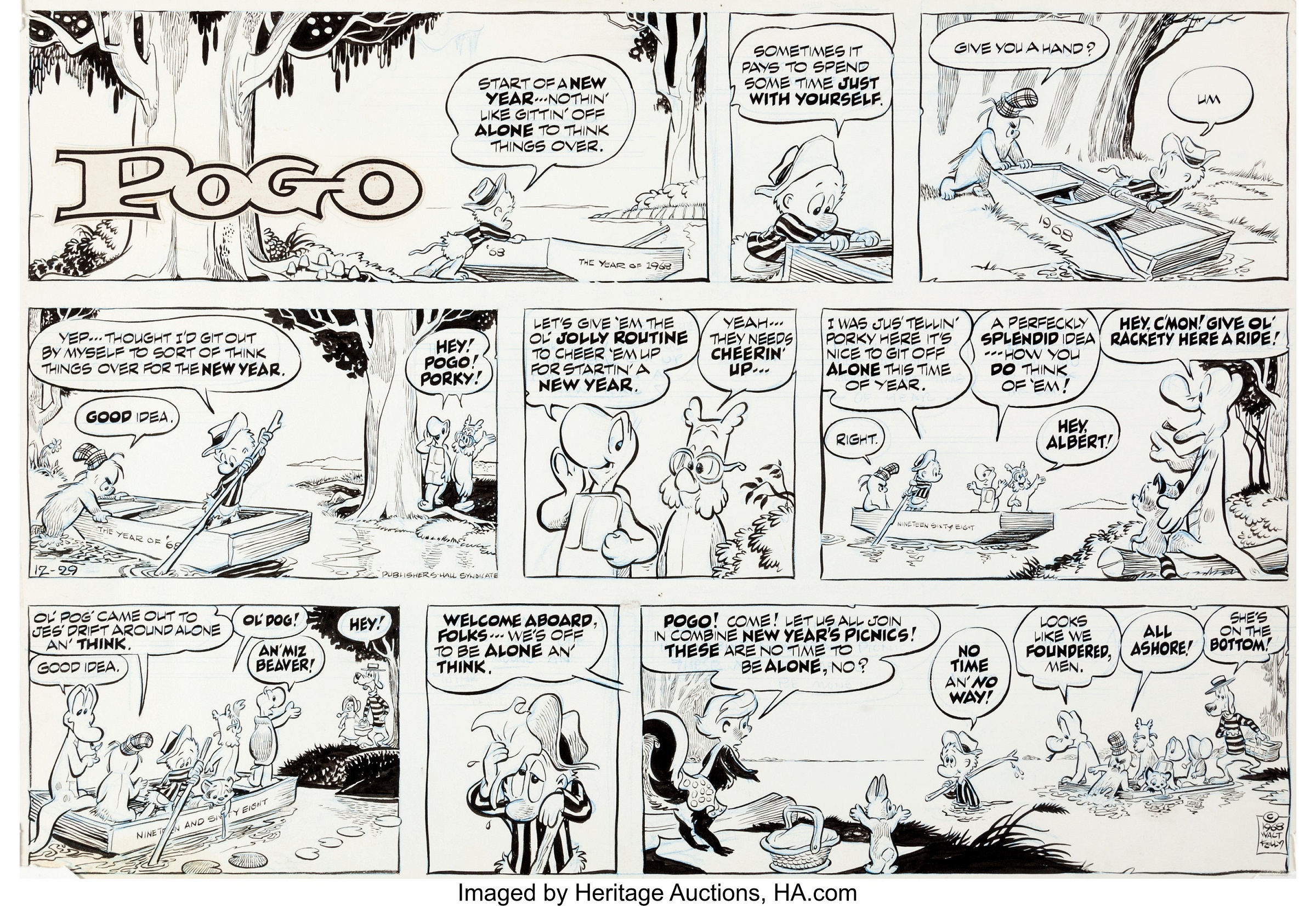

Walt Kelly (1913-1973) seemed to be the only one with a plausible answer. Kelly was an American cartoonist and animator. He worked for Walt Disney studios until 1941, when he moved over to Dell Comics. There, he created a new lineup of animal cartoon characters, including Pogo Possum, Albert Alligator and Churchill LaFemme. The strip was layered with clever political satire. On Earth Day 1971, his son was complaining about sore feet from having to walk on all the tin cans, glass and junk that had accumulated in the swamp. This was when Pogo uttered his most famous observation … “Yep, son, we have met the enemy and he is us.”

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].