By Jim O’Neal

In the 1830s, word started spreading about an Underground Railroad. A train with no tracks, no locomotive and no tickets needed to ride. From one plantation to the next, rumors spread about a “railroad to freedom” with no timetables and a crew that consisted of good citizens in the finest traditions of a young nation’s civil disobedience. In addition to helping fugitive slaves elude slave-hunters working for owners, Quakers, Protestants, Catholics and even American Indians were bound by their determination to see slavery abolished everywhere. It was a broad constituency of black and white abolitionists from the major cities in the North, including those in the border states.

It inevitably grew into a direct challenge to the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which specifically required the return of runaway slaves, even after they had safely reached non-slave states.

This law was possibly the most controversial aspect of the more comprehensive “Compromise of 1850,” and it quickly became nicknamed the “Bloodhound Law” for obvious reasons. Black newspapers went a step further by labeling it “manstealing,” from the Bible’s Exodus 21:16: “And he that stealeth a man, and selleth him, or if he be found in his hand, he shall surely be put to death.” The law also included a proviso to discourage anyone from obstructing the return of a slave by imposing a fine of $1,000 and imprisonment up to six months.

Naturally, many slaves who made the decision to escape merely walked away without any elaborate escape plans. Traveling at night and hoping to find strangers en route to assist them was more risky, but they were determined to follow their North Star. Others planned their escapes carefully by surreptitiously building up a supply of food and money and, if lucky, using a “conductor” who knew safe routes and people who would help. There also were slaves who decided not to risk escape, but were more than willing to aid and abet along the way.

Once a slave crossed the border into the North, there was a network of Underground Railroad people to assist. In addition to food, water and basic nursing, it was also possible to get “papers” that identified them as freedmen – then get directions to the next station. Churches, stables and even attics (a la Anne Frank) became good hiding places until they could get far enough north. Canada became a safe spot, just as it would be the next century during the Vietnam War.

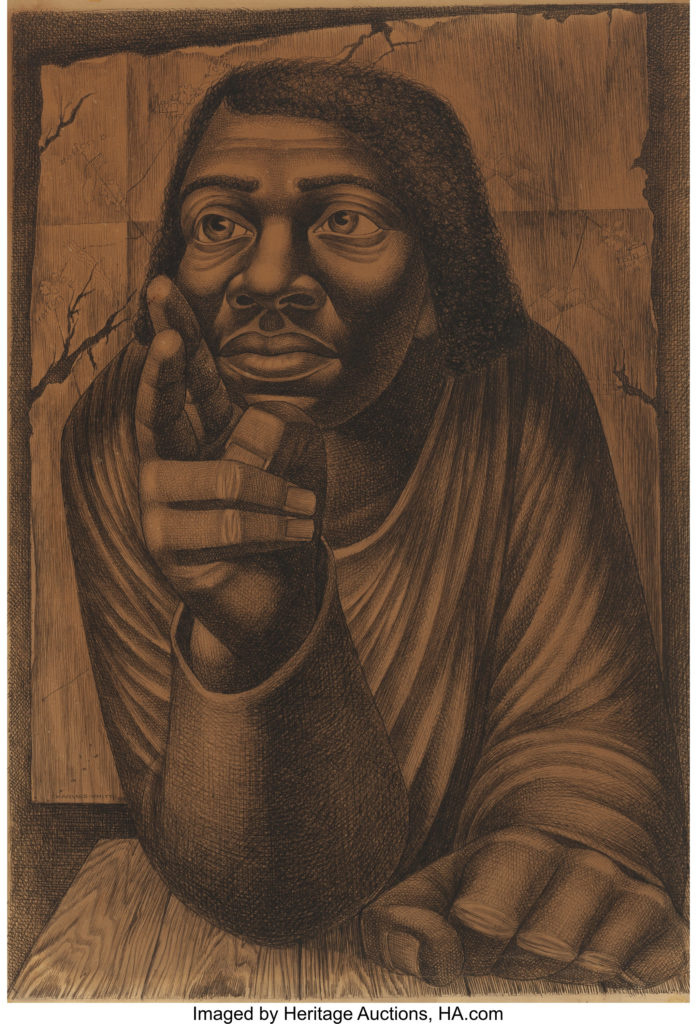

Among the Underground Railroad’s more heroic engineers was the ex-slave Harriet Tubman (c.1822-1913), a native of Maryland’s Eastern Shore who escaped to Philadelphia in 1849. Once free, she wrote: “I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person. There was such a glory over everything … and I felt like I was in Heaven.” Her own escape made Tubman determined to rescue as many slaves from bondage as she could. Her trips were made during the winter months when nights were long. Escapes began on Saturday nights; the slaves would not be missed until Monday. When “wanted” posters went up, she paid black men to tear them down. She kept a supply of paregoric to put babies to sleep so their cries would not raise suspicion.

She carried a gun, not simply for protection, but as inspiration – to threaten anyone in her group feigning fatigue. For her, the welfare of the entire group was paramount. If pursuers got too close, she would hustle her people on a southbound train, a ruse that worked because authorities never expected fugitives to flee in that direction. In addition to slaves, she helped John Brown recruit men for the infamous Raid on Harpers Ferry and worked as a cook, nurse and an armed scout for the U.S. Army after the war started.

Prominent abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison compared her to “Moses,” who led the Hebrews to freedom from Egypt, but this Moses never lost a man. The Moses in Exodus spent 40 years wandering in the desert and then put the future Israelites in the only place in the Middle East with no oil!

Harriet “Moses” Tubman was asked why she was not afraid. She answered: “I can’t die but once.”

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

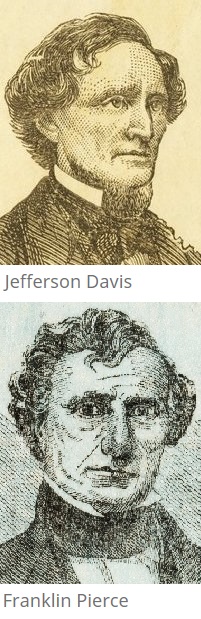

In 1819, the United States was a divided nation with 11 states that permitted slavery and an equal number that did not. When Missouri applied for admission to join the Union as a slave state, tensions escalated dramatically since this would upset the delicate balance. It would also set a precedent by establishing the principle that Congress could make laws regarding slavery, a right many believed was reserved for the states.

In 1819, the United States was a divided nation with 11 states that permitted slavery and an equal number that did not. When Missouri applied for admission to join the Union as a slave state, tensions escalated dramatically since this would upset the delicate balance. It would also set a precedent by establishing the principle that Congress could make laws regarding slavery, a right many believed was reserved for the states.