By Jim O’Neal

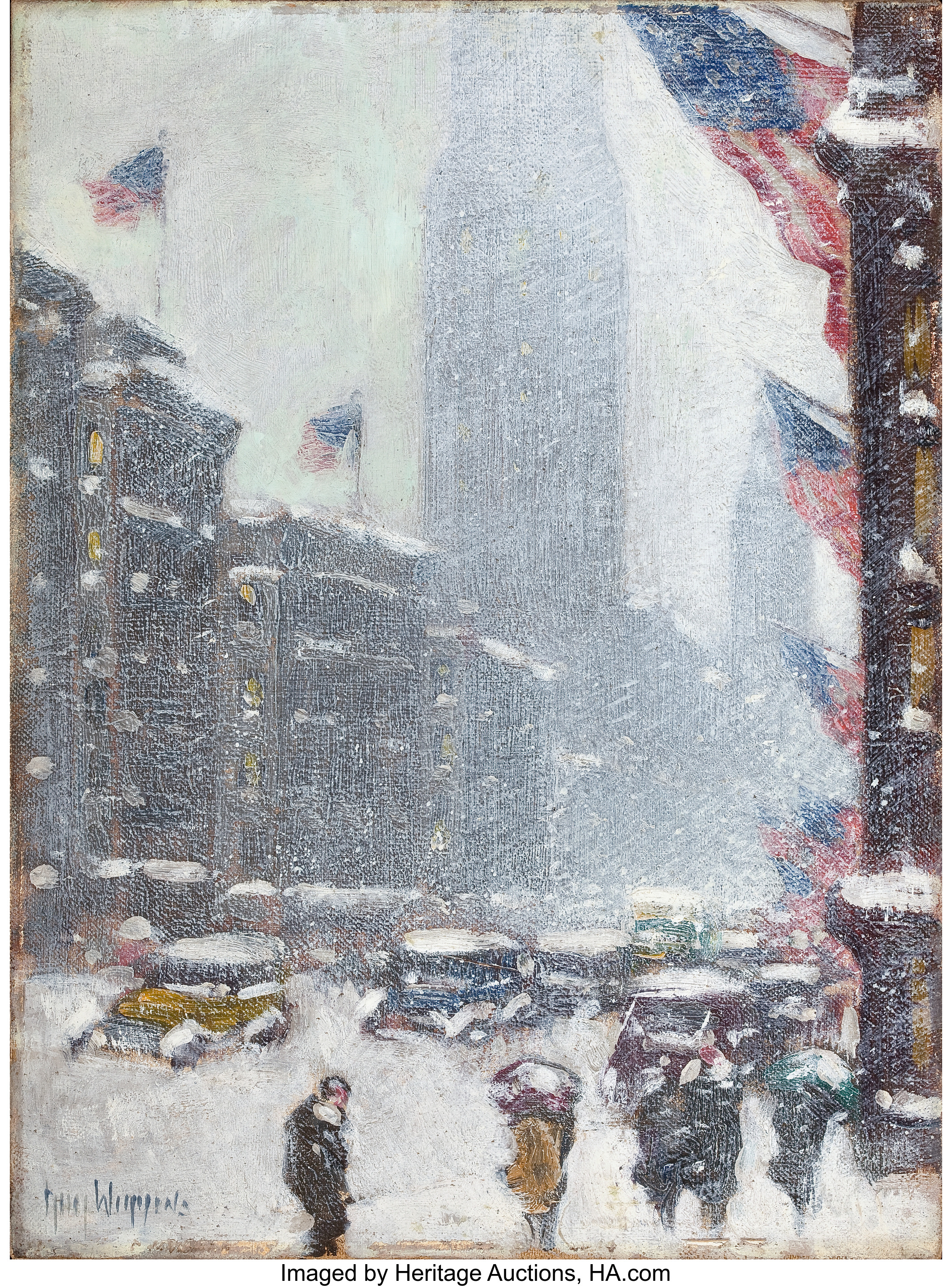

“From the ruins, lonely and inexplicable as the Sphinx,” F. Scott Fitzgerald once wrote, “rose the Empire State Building.”

The “ruins” was an oblique reference to the stock market crash in 1929. Completed on May 1, 1931, on the site where the Waldorf Astoria had stood, no building ever reached so high, so fast; 102 stories tall and with a 200-foot mast to hitch your dirigible. It was built in just over a year, during what would become the nation’s worst depression.

Just a short two years earlier on May 1, 1929, architect William Van Alen had broken ground on the Chrysler Building. He had been commissioned by Chrysler to design and construct the tallest building in the world. When the Chrysler Building opened in April 1930, it was indeed the tallest at a magnificent 925 feet – a world record that would only stand for a fleeting 28 days! Then the Manhattan Bank Tower completed its construction and opened at a height of 927 feet, which allowed it to lay claim to the World’s Tallest title by a measly 2 feet.

Hang on. The race wasn’t over. In the history of high wire, where one-upmanship is the oxygen that fuels architectural competition, the Chrysler Building’s William Van Alen had kept a surprise hidden up his sleeve that would allow him to reclaim this prestigious crown.

Van Alen had designed a stainless spire of five sections, which was lowered through the top of the building. At a fixed time, before a highly appreciative audience, Van Alen delivered his coup de grâce to the Manhattan Bank. A huge derrick, its gears slowly turning, raised the spire from the innards of the Chrysler Building. “It gradually emerged,” Van Alen wrote, “from the top of the dome like a butterfly from its cocoon.” At 1,046 feet, the Chrysler Building was suddenly, once again, the World’s Tallest Building.

Alas, it only remained so for less than a year, when the Empire State Building – topping out at 1,250 feet – grabbed the title for itself. It would retain the crown until 1971 when the World Trade Center towers opened. Fittingly, the group behind the Empire State Building included the Happy Warrior himself, Al Smith, former governor of New York (four times) and the Democratic candidate for president in the 1928 election (won by Herbert Hoover). Smith’s grandchildren cut the ribbon when the world’s (newest) tallest skyscraper opened May 1, 1931, and President Hoover turned on the building’s lights using a remote push button in Washington, D.C.

Subsequently, the building has become a worldwide icon and in 1994 it was named one of the “Seven Wonders of the Modern World” by the American Society of Civil Engineers … joining the Golden Gate Bridge and the Panama Canal, all American architectural marvels. Plus, who can forget Fay Wray as Ann Darrow in the 1933 classic King Kong, when the beast from Skull Island plucks her from the building?

The Empire State Building took only 410 days to build since the architectural firm used design plans for the (similar but smaller) Reynolds Building in Winston-Salem, N.C., a project they had worked on earlier. The staff at the Empire State Building sends a Father’s Day card to the Reynolds Building each year to honor the contribution it made to their existence.

Although long since surrendering its crown for height, the Empire State Building is a “must see” for all tourists to New York and, amazingly, revenue from ticket sales for admission to the observation decks exceeds office space rental income.

Its place in history seems quite secure.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].