By Jim O’Neal

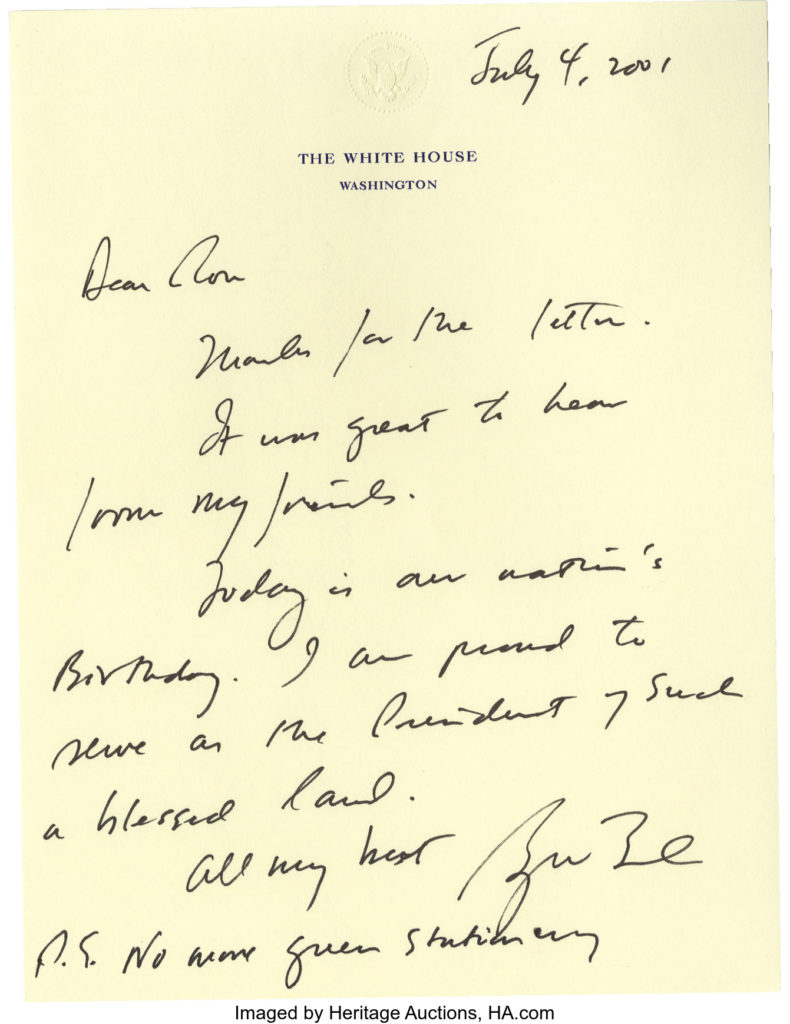

In May 2001 – just 126 days after President George W. Bush took office – Congress passed his massive tax proposal. The Bush tax cuts had been reduced to $1.3 trillion from the $1.65 trillion submitted, but it was still a significant achievement from any historical perspective. It had taken Ronald Reagan two months longer to win approval of his tax cut and that was 20 years earlier.

Bush was characteristically enthusiastic about this, but it had come with a serious loss in political capital. Senator James Jeffords, a moderate from Vermont, announced his withdrawal from the Republican Party, tipping control of the Senate to the Democrats, the first time in history that had occurred as the result of a senator switching parties. In this instance, it was from Republican to Independent, but the practical effect was the same. Several months later (after the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon), there was a loud chorus of calls to reverse the tax cuts to pay for higher anticipated spending.

Bush had a counter-proposal: Cut taxes even more!

Fiscal conservatives were worried that there would be the normal increase in the size and power of the federal government, lamenting that this was a constant instinctive companion of hot wars. James Madison’s warning that “A crisis is the rallying cry of the tyrant” was cited against centralization that would foster liberal ideas about the role of government and even more dependency on the federal system.

Ex-President Bill Clinton chimed in to say that he regretted not using the budget surplus (really only a forecast) to pay off the Social Security trust fund deficit. Neither he nor his former vice president had dispelled the myth about a “lock box” or explained the federal building in Virginia that had been built exclusively to hold government IOUs to Social Security. In reality, they were simply worthless pieces of scrip, stored in unlocked filing cabinets. The only changes that had ever occurred with Social Security funds were whether they were included in a “unified budget” or not. They had never been kept separate from other revenues the federal government received.

But this was Washington, D.C., where, short of a revolution or civil war, change comes in small increments. Past differences, like family arguments, linger in the air like the dust that descends from the attic. All of the huge surpluses totally disappeared with the simple change in the forecast and have never been discussed since.

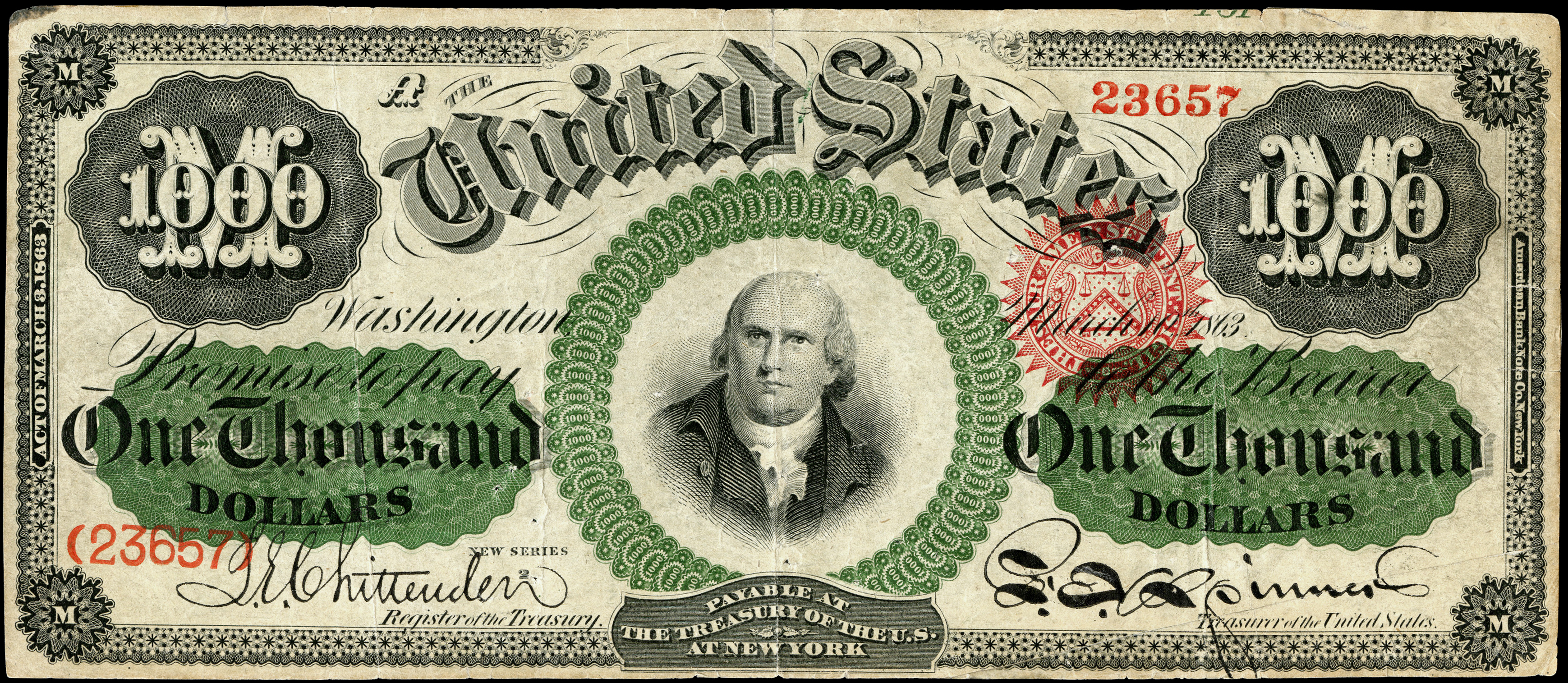

Back at the Treasury Department of 15th Street, a statue to Alexander Hamilton commemorates the nation’s first Treasury Secretary, a fitting honor to the man who created our fiscal foundation. But on the other side stands Albert Gallatin, President Thomas Jefferson’s Treasury Secretary, who struggled to pay off Hamilton’s debts and shrink the bloated bureaucracy he built.

Hamilton also fared better than his onetime friend and foe, James Madison. The “Father of the Constitution” had no statue, no monument, no lasting tribute until 1981, when the new wing of the Library of Congress was named for him. This was a drought that was only matched by John Adams, the Revolutionary War hero and ardent nationalist. It was only after a laudatory biography by David McCulloch in 2001 that Congress commissioned a memorial to the nation’s second president.

Since the Bush tax cut and the new forecast, the national debt has ballooned to $20 trillion as 9/11, wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the 2008 financial meltdown produced a steady stream of budget deficits in both the Bush and Barack Obama administrations. The Donald Trump administration is poised to approve tax reform, amid arguments on the stimulative effect on the economy and who will benefit. In typical Washington fashion, there is no discussion over the fact that the national debt is inexorably on automatic pilot to $25 trillion, irrespective of tax reform. But this is Washington, where your money (and all they can borrow) is spent almost with no effort.

“Just charge it.”

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].