By Jim O’Neal

The Supreme Court was created by the Constitution, but the document wisely calls for Congress to decide the number of justices. This was vastly superior to a formula based on the number of states or population, which would have resulted in a large, unwieldy committee. The 1789 Judiciary Act established the initial number at six, with a chief justice and five associates all selected by President Washington.

In 1807, the number was increased to seven (to avoid tie votes) and in 1837 to nine, and then to 10 in 1863. The Judiciary Act of 1866 temporarily reduced the court to seven in response to post-Civil War politics and the Andrew Johnson presidency. Finally, the 1869 Act settled on nine, where it has remained to this day. The major concern has consistently been over the activities of the court and the fear it would inevitably try to create policy rather than evaluate it (ensuring that Congressional legislation was lawful and conformed to the intent of the Constitution).

The recent confirmation hearings are the latest example of both political parties vying for advantage by using the court to shape future policies, reflecting political partisanship at its worst. Despite the fact that the Supreme Court can’t enforce its decisions since Congress has the power of the purse and the president the power of force, the court has devolved into a de facto legislative function through its deliberations. In a sharply divided nation, on most issues, policy has become the victim, largely since Congress is unable to find consensus. The appellate process is simply a poor substitute for this legislative weakness.

We have been here before and it helps to remember the journey. Between 1929 and 1945, two great travails were visited on our ancestors: a terrible economic depression and a world war. The economic crisis of the 1930s was far more than the result of the excesses of the 1920s. In the 100 years before the 1929 stock-market crash, our dynamic industrial revolution had produced a series of boom-bust cycles, inflicting great misery on capital and on many people. Even the fabled Roaring ’20s had excluded great segments of the population, especially blacks, farmers and newly arrived immigrants. Who or what to blame?

“[President] Hoover will be known as the greatest innocent bystander in history, a brave man fighting valiantly, futile, to the end,” populist newspaperman William Allen White wrote in 1932.

The same generation that suffered through the Great Depression was then faced with war in Europe and Asia, the rationing of common items, entrance to the nuclear age and, eventually, the responsibilities for rebuilding the world. Our basic way of life was threatened by a global tyranny with thousands of nukes wired to red buttons on two desks 4,862 miles apart.

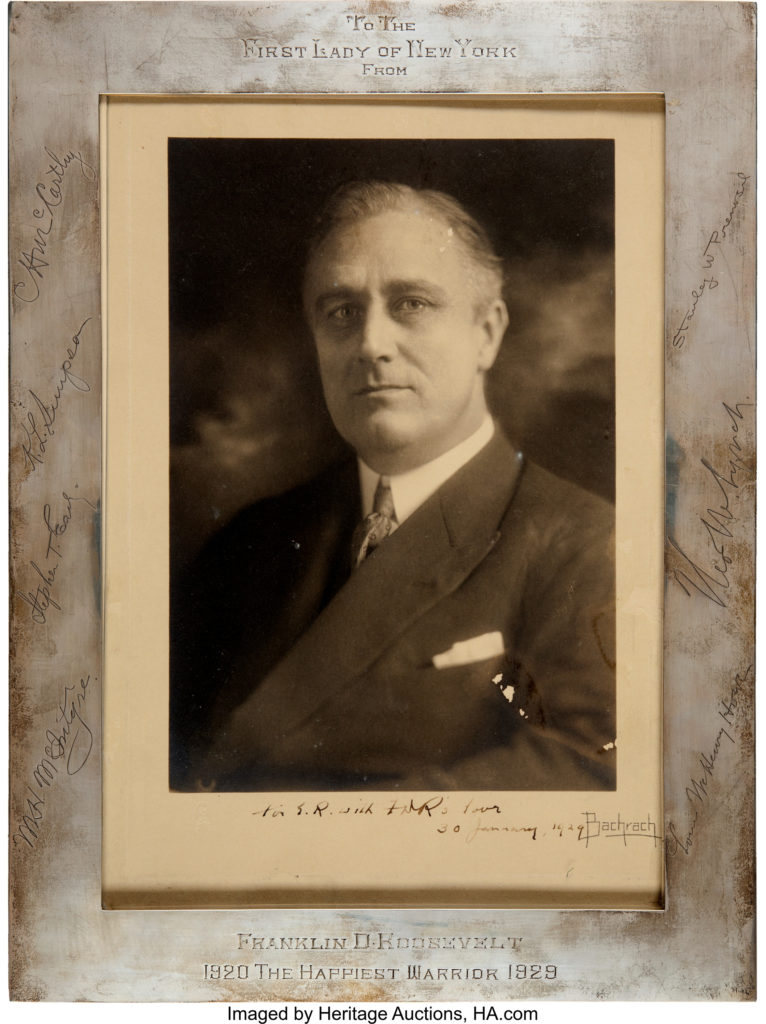

FDR was swept into office in 1932 during the depth of the Great Depression and his supporters believed he possessed just what the country needed: inherent optimism, confidence, decisiveness, and the desire to get things done. We had 13 million unemployed, 9,100 banks closed, and a government at a standstill. “This nation asks for action and action now!”

In his first 100 days, Roosevelt swamped Congress with a score of carefully crafted legislative actions designed to bring about economic reforms. Congress responded eagerly. But the Supreme Court, now dubbed the “Nine Old Men,” said no to most New Deal legislation by votes of 6-3 or 5-4. They made mincemeat of the proposals. But the economy did improve and resulted in an even bigger landslide re-election. FDR won 60.3 percent of the popular vote and an astonishing 98.5 percent of the electoral votes, losing only Vermont and Maine.

In his 1937 inaugural address, FDR emphasized that “one-third of the nation was ill-housed, ill-clad and ill-nourished.” He called for more federal support. However, Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau worried about business confidence and argued for a balanced budget, and in early 1937, Roosevelt, almost inexplicably, ordered federal spending reduced. Predictably, the U.S. economy went into decline. Industrial production had fallen 14 percent and in October alone, another half million people were thrown out of work. It was clearly now “Roosevelt’s Recession.”

Fearing that the Supreme Court would continue to nullify the New Deal, Roosevelt in his ninth Fireside Chat unveiled a new plan for the judiciary. He proposed that the president should have the power to appoint additional justices – up to a maximum of six, one for every member of the Supreme Court over age 70 who did not retire in six months. The Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937 (known as the “court-packing plan”) hopelessly split the Democratic majority in the Senate, caused a storm of protest from bench to bar, and created an uproar among both Constitutional conservatives and liberals. The bill was doomed from the start and even the Senate Judiciary reported it to the floor negatively, 10-14. The Senate vote was even worse … 70-20 to bury it.

We know how that story ended, as Americans were united to fight a Great War and then do what we do best: work hard, innovate and preserve the precious freedoms our forebears guaranteed us.

Unite vs. Fight seems like a good idea to me.

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].