By Jim O’Neal

Important scholars believe that Simón Bolívar should have been the George Washington of South America. He, too, overthrew an empire (Spain) – but obviously failed to create an Estados Unidos of South America. The American Revolution not only achieved unity for the former British colonies; independence also set the United States on the road to unsurpassed prosperity and power. South America ended up in a different place entirely due to a complex set of events.

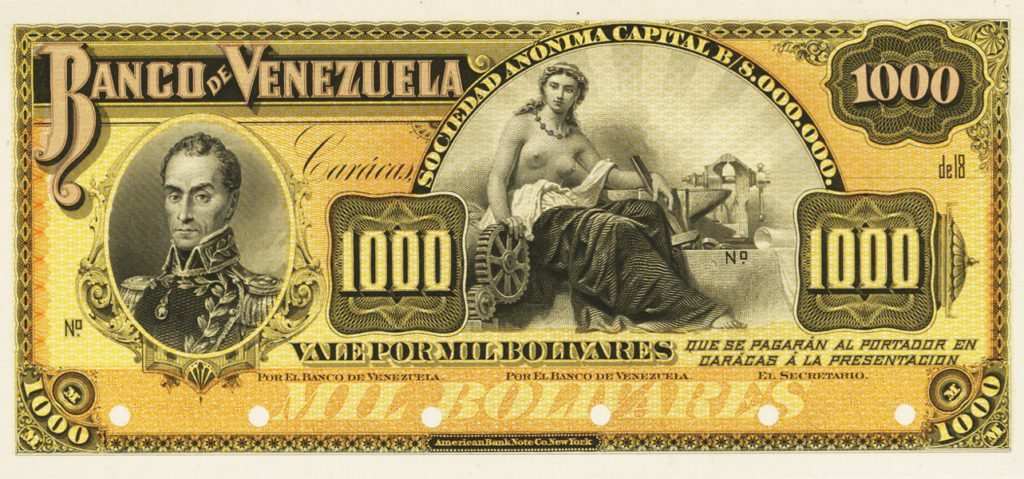

Bolívar was born in Caracas in July 1783 to a prosperous, aristocratic family. He was an orphan by age 10 and soldier at the tender age of 14. He studied in Spain and France, spending time in Paris even after all foreigners were expelled in response to a food shortage. He returned to Venezuela by 1807, inspired by Napoleon and disgusted with Spanish rule. Sent to London to seek British help, he met Francisco de Miranda, the veteran campaigner for Venezuelan independence.

On their return in July 1811, they boldly proclaimed the First Republic of Venezuela.

The Republic ended in failure since a disproportionate number were excluded from voting by a flawed constitution and Bolívar betrayed Miranda to the Spanish before fleeing to New Granada. From there, he proclaimed a Second Republic – with himself in the role of dictator and winning the epithet El Libertador.

Eventually, Bolívar became master of what he termed Gran Colombia, which encompassed New Granada, Venezuela and Quito (modern Ecuador). José de San Martín, the liberator of Argentina and Chile, yielded political leadership to him. By April 1825, his men had driven the last Spanish from Peru, and Upper Peru was renamed Bolivia in his honor. The next step was to create an Andean Confederation of Gran Colombia, Peru and Bolivia. Why did Bolívar fail to establish this as the core of a United States of Latin America? The superficial answer – his determination to centralize power and resistance of the local warlords – misses much more complicated circumstances.

First is that South Americans had virtually no experience or history in democratic decision-making or representative government of the sort that had been normal in North America’s colonial assemblies. So Bolívar’s dream of democracy turned out to be dictatorship because, as he once said, “our fellow citizens are not yet able to exercise their rights … because they lack the political virtues that characterize true republicans.” Under the constitution he devised, Bolívar was to be dictator for life, with the right to nominate his successor. “I am convinced to the very marrow of my bones that America can only be ruled by an able despotism … We cannot afford to place laws above leaders and principles above men.”

For remaining skeptics, perhaps it is better to let Simón Bolívar explain in his own words, in a December 1830 letter he wrote a month before his death:

“I ruled for 20 years … and I derived only a few certainties:

- South America is ungovernable.

- Those who serve a revolution plough the sea.

- The only thing one can do in America is to emigrate.

- This country will fall inevitably into the hands of the unbridled masses.

- Once we have been devoured by every crime and extinguished by utter ferocity, the Europeans will not even regard us as worth conquering.

- If it were possible for any part of the world to revert to primitive chaos, it would be [South] America in her final hour.”

This was a painfully accurate prediction for the next 150 years of Latin American history and the result was a cycle of revolution and counter-revolution, coup and counter-coup. One only needs to read of Venezuela today to grasp the totality of how dire the future remains.

By the way, much of this insight comes by way of the highly recommended Civilization: The West and the Rest by Niall Ferguson.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].