By Jim O’Neal

By 1775, North and South America had become remarkably different from a societal standpoint, with economic systems profoundly dissimilar. The only significant similarity was they were both still composed of colonies ruled by kings in distant lands.

That was about to change, rather dramatically.

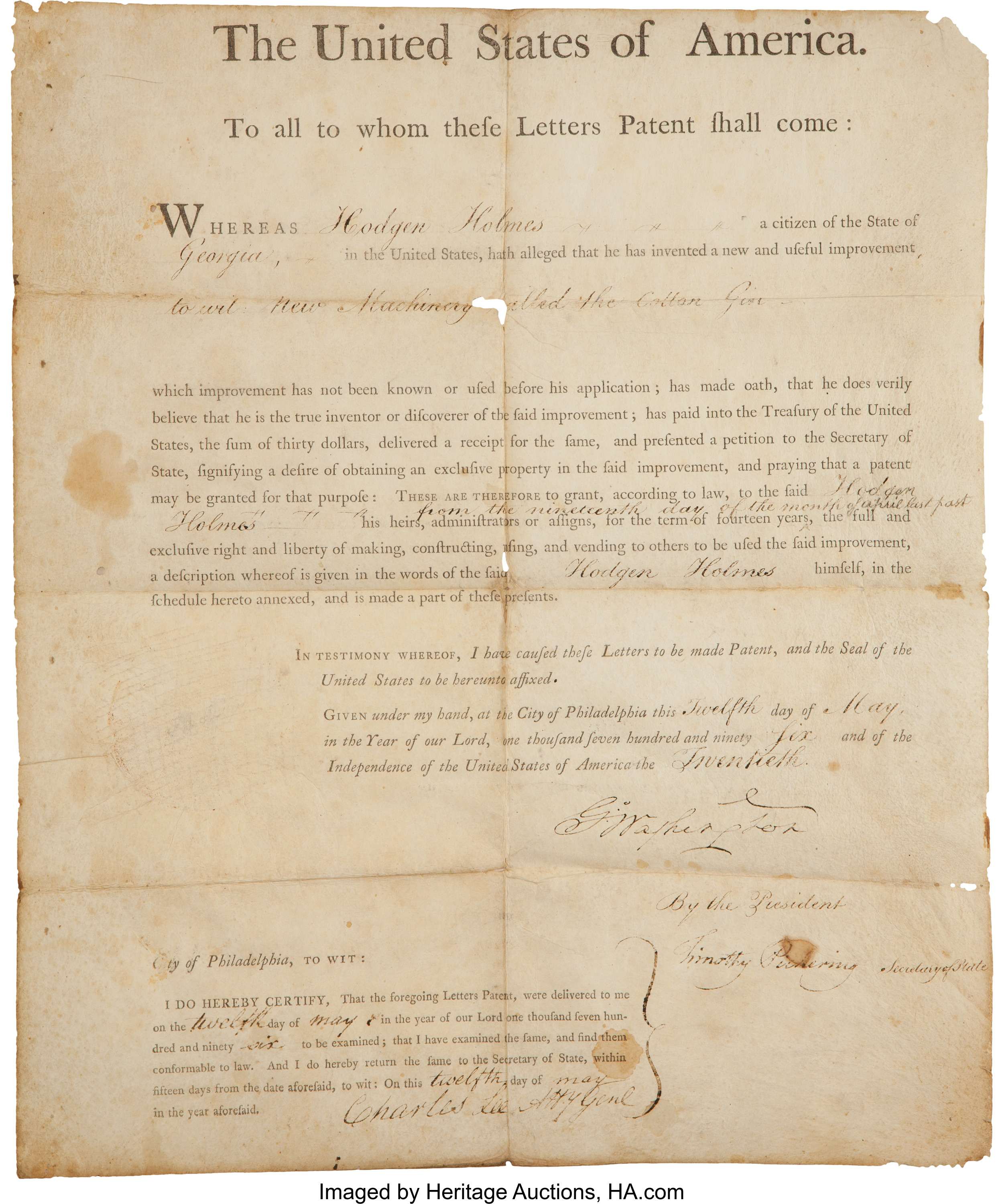

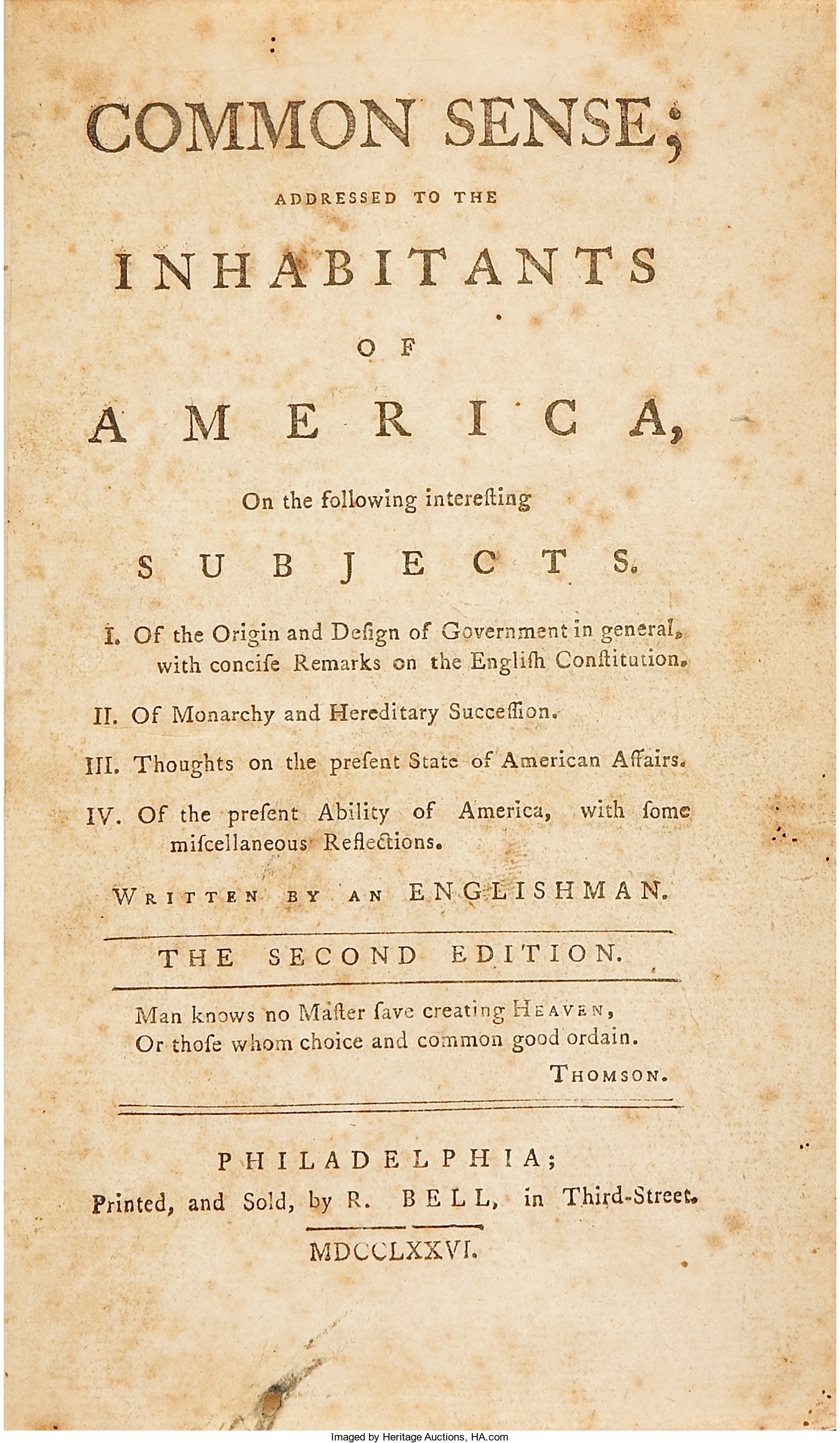

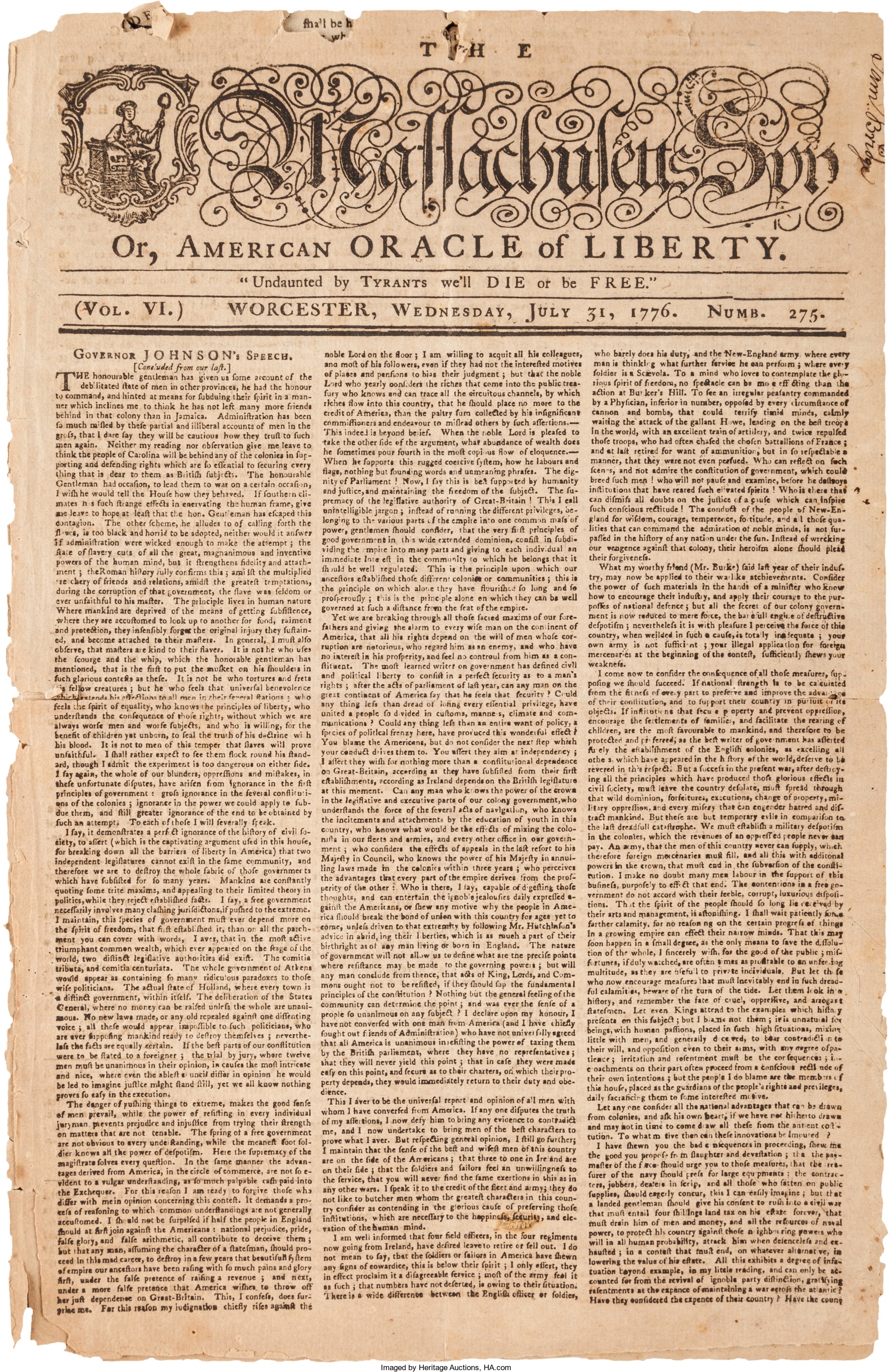

On July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress declared its colonies independent from Britain and King George. Spain’s rule in Latin America would end 40 years later, but the North’s revolution assured the rights of property owners and established a federal republic that would become the world’s wealthiest nation in a relatively short 100 years.

Latin American revolutions, on the other hand, consigned nations south of the Rio Grande to 200 years of instability, disunity and economic underdevelopment.

One important reason was that the independence claimed by Britain’s 13 North American colonies was driven by a libertarian society of merchants and farmers who rebelled against an overzealous extension of imperial authority. It was not only the old issues of taxation and representation; land had become a much more important issue that, in turn, fueled the revolutionary fires. The British government’s efforts to limit further settlement west of the Appalachians struck at the heart of the colonists’ vision of the future – a vision of “manifest larceny” that was especially attractive to property speculators like George Washington.

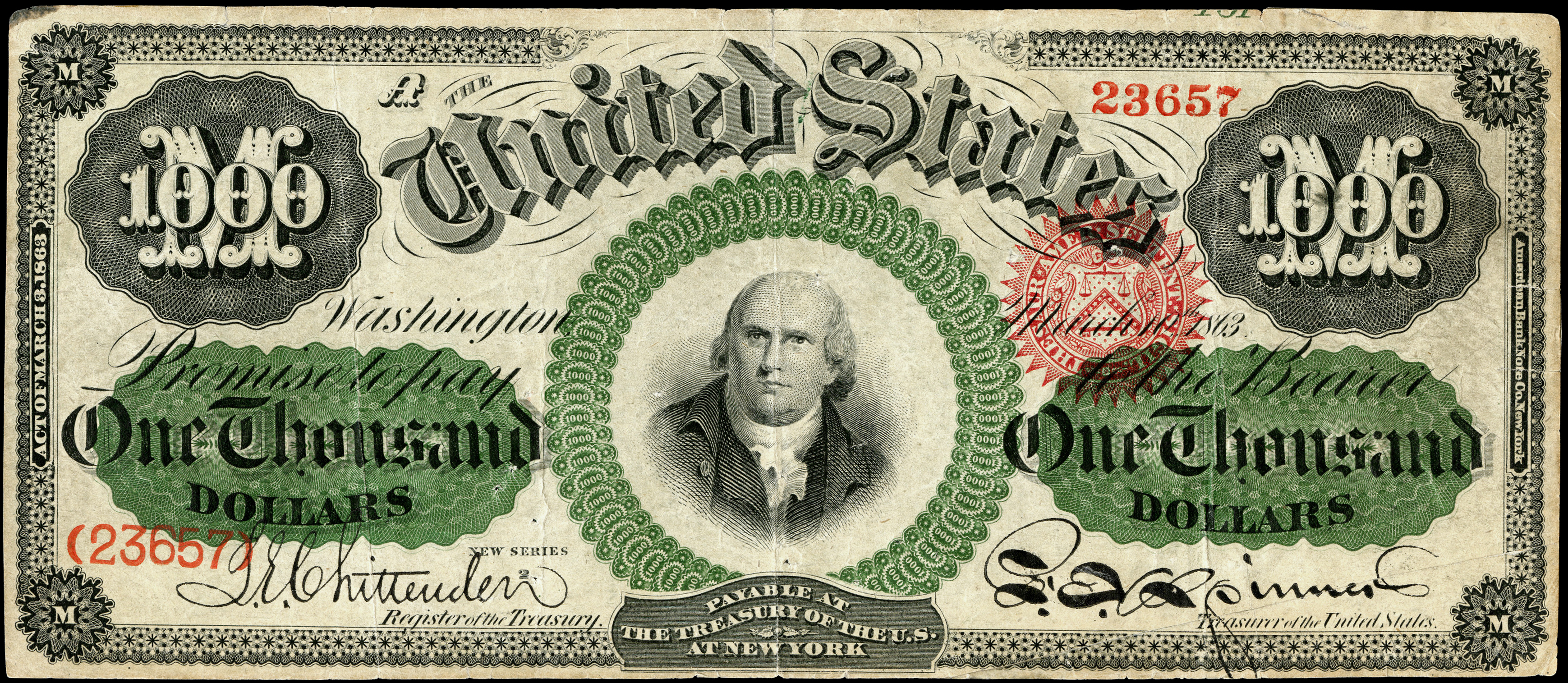

Still, war may have been averted by concessions on taxes, better diplomacy or even if British generals were more adept and less arrogant. It is even possible to imagine the colonies falling apart instead of coming together. Post-war economic conditions were severe: inflation near 400 percent, per capita income slashed by 50 percent, a mountain of debt over 60 percent of GDP. But losing the yoke of the British Crown created a sense of newfound freedom and brotherhood. These states were now united.

However, had the revolution not progressed beyond the Articles of Confederation, then perhaps the fate of the United States would have been more like that of South America – a story of fragmentation rather than unification. It took the Constitution of 1787, the most impressive piece of political institution-building in all of history, to establish a viable federal structure for the new republic. There was a single market, a single trade policy, a single currency, a single army, and a single law of bankruptcy for people whose debts exceeded assets.

The major flaw was not resolving the issue of slavery and the naive assumption it would vanish over time. It obviously did not and the burden of the Civil War nearly destroyed all of the astonishing progress that followed. The sheer brilliance of Abraham Lincoln’s insight to avoid any action that would lead to disunion trumped the temptation to co-mingle states’ rights or slavery. “One nation, indivisible…”

Yet independence from Spain left much of Latin America with an enduring legacy of conflict, poverty and inequality. Why did capitalism and democracy fail to thrive?

The short answer was Simón Bolívar.

A longer, more balanced view will have to wait for its own blog entry.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].