By Jim O’Neal

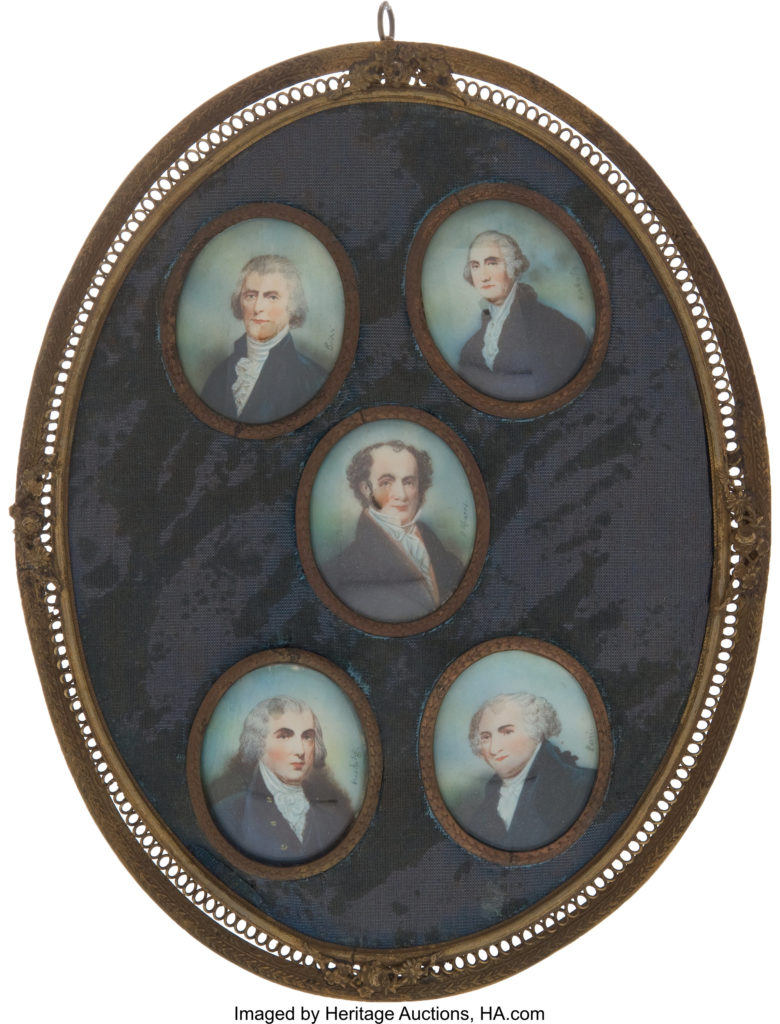

It is always a pleasant surprise to discover an obscure name that has been lost in the sands of America’s history. Charles Thomson (1729-1824) falls into that category. He was Secretary of the Continental Congress from 1774 continuously until the U.S. Constitution was firmly in place and the bi-cameral government was functioning in 1789.

He was also the only non-delegate to actually sign the Declaration of Independence. A surprisingly active participant in the Revolutionary War, he wrote a 1,000-page manuscript on the politics of the times. It included the formation of the Continental Congress and a daily recap of speeches and debates right up to the agreement to go forward. In concept, it was a remarkable, contemporary record that is unique (except for notes James Madison complied). The public was not allowed to even attend the meetings in Philadelphia.

Alas, Thomson’s manuscript was never published since he destroyed it. Purportedly, it was because he wanted to preserve the reputations of these heroes and assumed that others would write about these historic times. The obvious implication is that his candid verbatim notes might tarnish some of his fellow colleagues. Thomson receives credit for helping design the Great Seal of the United States and since he personally chose what to include in the official journal of the Continental Congress, we’re left to wonder what he omitted or later burned … another example of why history is normally not considered precisely correct.

As Secretary of the Congress, Thomson personally rode to Mount Vernon, Va., and delivered the news to George Washington that he had been elected president of the United States. He told Washington that Congress was delighted he’d agreed “to sacrifice domestic ease and private enjoyments to preserve the happiness of your country.” Washington, in turn, said he couldn’t promise to be a great president, but could promise only “that which can be done by honest zeal.”

Political pundits opine that the office of the president was perfectly suited for George Washington, especially during the early formative years of the nation. A well-known hero in the fight for independence, he was a national leader who gained power without compromising himself or his principles. Absent the burden of a political party, he could have easily assumed the kind of monarchical power the nation had fought against. But, like his hero Cincinnatus, he had laid down his sword and returned to the plow. Clearly, this was a case of the office seeking the man as opposed to the reverse.

Washington truly did not aspire to the presidency – perhaps unique compared to all the men who followed. In his own words, he considered those eight years a personal sacrifice. In that era, land was the ultimate symbol of wealth and prestige. Through inheritance, he had acquired Mount Vernon and roughly 2,000 acres. That was not close to satisfying his ambitions and he spent much of his private life in a search of more … much more!

Historian John Clark called him an “inveterate land-grabber” and there’s plenty of evidence to support the claim. In 1767, he grabbed land set aside for Indians by the Crown by telling the surveyor to keep it a secret. This was followed by another 20,000 acres designated for soldiers in the French and Indian War. Washington arranged for officers to participate and then bought the land after telling the solders it was hilly, scrubby acreage. Washington would later boast that he had received “the cream of the country.”

Most biographies have been consistent in pointing out that land may have been a prime factor in his decision to court the widow Martha Parke Custis. They invariably point to his strong affection for Sally Fairfax, but she was his best friend’s wife. Martha was not without attraction. As one of the richest widows in North America, her marriage to George resulted in a windfall since what was hers became his. In addition to nearly 100 slaves, her 6,000 acres made George a very rich man. Details of their relationship are not available since Martha burned their love letters after his death.

However, since slaves over 12 were taxed, there are public records. During the first year of their marriage (he was 26 and she was 28), he acquired 13 slaves, then another 42 between 1761 and 1773. From tax records, we know he personally owned 56 slaves in 1761 … 62 in 1762 … 78 in 1765 … and 87 in the 1770s. Washington, Jefferson, Madison and most Virginia planters openly acknowledged the immorality of slavery, while confessing an inability to abolish it without financial ruin.

Washington had a reputation for tirelessly providing medical treatment for his slaves. But, was it for regard of property or more humane considerations? I suspect the answer lies somewhere in between.

As the first president, the paramount issue – among the many priorities of his first term – was to resolve the new government’s crushing debt. In 1790, the debt was estimated at $42 million. It was owed to common citizens of modest means and to thousands of Revolutionary War veterans whose IOUs had never been redeemed as stipulated by the Articles of Confederation. The war pension certificates they held had declined dramatically by 15 to 20 percent of face value.

Raising taxes was too risky and states might rebel. Ignore the debt, as had been the custom for several years, and the federal government risked its already weak reputation. The new president had to turn to his Cabinet for advice. He had an excellent eye for talent and the brilliant Alexander Hamilton was Treasury Secretary. He quickly formed a plan to create a new Bank of the United States (BUS). Since the bank would be backed by the federal government, people would feel safer about lending money and, as creditors, they would have a stake in both the bank and the government. Although Thomas Jefferson opposed the BUS, Washington prevailed in Congress.

Washington was re-elected four years later, again with a unanimous vote in the Electoral College. The first popular voting would not occur until 1824 and since that time, five presidential candidates have been elected despite losing the popular vote: John Quincy Adams (1824), Rutherford Hayes (1876), Benjamin Harrison (1888), George W. Bush (2000), and Donald J. Trump (2016).

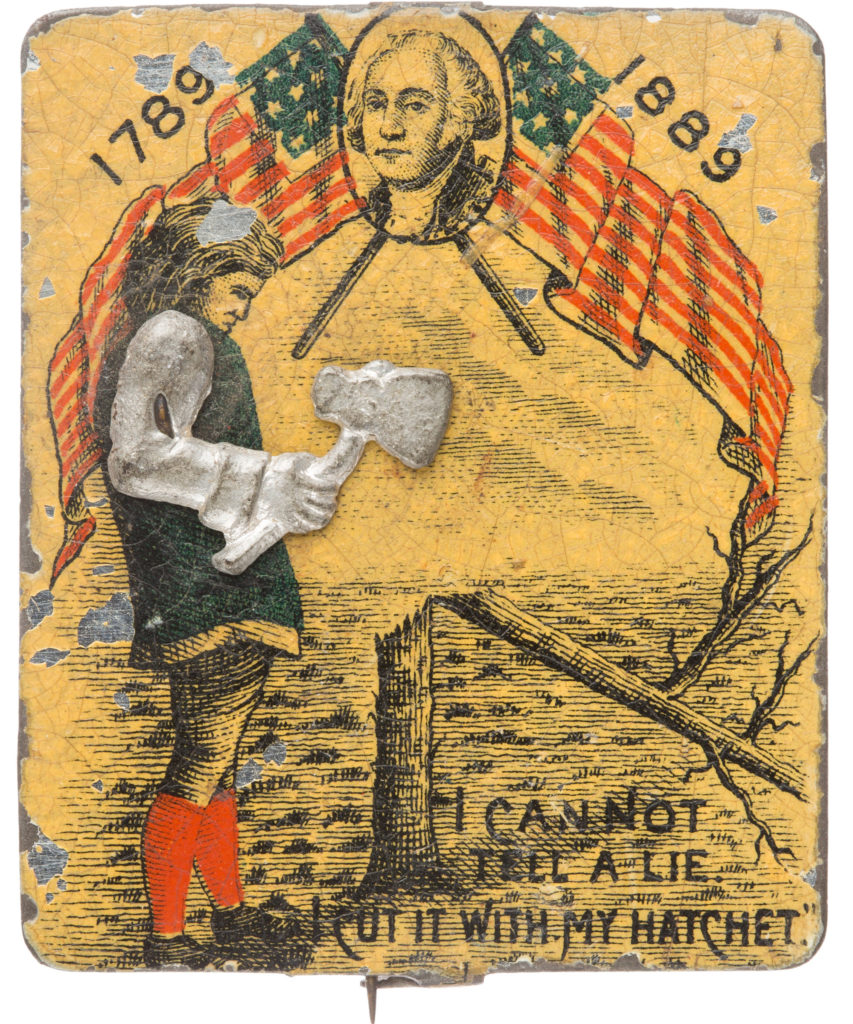

It’s not easy starting a new country. There were no cherry trees to chop down as Parson Weems’ story describes. George Washington did not throw a silver dollar across the Rappahannock River. These are all fairy tales that grew over time. Yes, George Washington owned slaves and told a lie now and then. He was obsessed with land at one time. But, when it came to crunch time, he stepped up and committed eight years of his life to his country.

The big question now seems to be where we’ll find another man or woman to continue the story of the greatest country in history?

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].