By Jim O’Neal

It seems clear that one of the bedrock fundamentals that contributes to the stability of the U.S. government is the American presidency. Even considering the terrible consequences of the Civil War – 11 states seceding, 620,000 lives lost and widespread destruction – it’s important to remember that the federal government held together surprisingly well. The continuity of unbroken governance is a tribute to a success that is the envy of the world.

Naturally, the Constitution, our system of justice and the rule of law – along with all the other freedoms we cherish – are all critical contributors. But it’s been our leadership at the top that’s made it all possible. In fact, one could argue that having George Washington as the first president for a full eight years is equal in importance to all other factors. His unquestioned integrity and broad admiration, in addition to precedent-setting actions, got us safely on the road to success despite many of the governed being loyal to the British Crown.

Since that first election in 1789, 44 different men have held the office of president (Grover Cleveland for two separate terms), and six of them are alive today. I agree with Henry Adams, who argued, “A president should resemble a captain of a ship at sea. He must have a helm to grasp, a course to steer, a port to seek. Without headway, the ship would arrive nowhere and perpetual calm is as detrimental to purpose as a perpetual hurricane.” The president is the one who must steer the ship, as a CEO leads an organization, be it small or large.

In the 229 intervening years, there have been brief periods of uncertainty, primarily due to vague Constitutional language. The first occurred in 1800, when two Federalists each received 73 electoral votes. It was assumed that Thomas Jefferson would be president and Aaron Burr would be vice president. The wily Burr spotted an opportunity and refused to concede, forcing the decision into the House. Jefferson and Burr remained tied for 35 ballots until Alexander Hamilton (convinced that Jefferson was the lesser of two evils) swayed a few votes to Jefferson, who won on the 36th ballot. This technical glitch was modified by the 12th Amendment in 1804 by requiring an elector to pick both a president and a vice president to avoid any uncertainty.

A second blip occurred after William Henry Harrison and John Tyler defeated incumbent Martin Van Buren. At age 68, Harrison was the oldest to be sworn in as president, a record he held until Ronald Reagan’s inauguration in 1981 at age 69. Harrison died 31 days after his inauguration (also a record), the first time a president had died in office. A controversy arose over the successor. The Presidential Succession Act of 1792 specifically provided for a special election in the event of a double vacancy, but the Constitution was not specific regarding just the presidency.

Vice President Tyler, at age 51, would be the youngest man to assume leadership. He was well educated, intelligent and experienced in governance. However, the Cabinet met and concluded he should bear the title of “Vice President, Acting as President” and addressed him as Mr. Vice President. Ignoring the Cabinet, Tyler was confident that the powers and duties fell to him automatically and immediately as soon as Harrison had died. He moved quickly to make this known, but doubts persisted and many arguments followed until the Senate voted 38 to 8 to recognize Tyler as the president of the United States. (It was not until 1967 that the 25th Amendment formally stipulated that the vice president becomes president, as opposed to acting president, when a president dies, resigns or is removed from office.)

In July 1933, an extraordinary meeting was held by a group of disgruntled financiers and Gen. Smedley Butler, a recently retired, two-time Medal of Honor winner. According to official Congressional testimony, Smedley claimed the group proposed to overthrow President Franklin Roosevelt because of the implications of his socialistic New Deal agenda that would create enormous federal deficits if allowed to proceed.

Smiley Darlington Butler was a U.S. Marine Corps major general – the highest rank authorized and the most decorated Marine in U.S. history. Butler (1881-1940) testified in a closed session that his role in the conspiracy was to issue an ultimatum to the president: FDR was to immediately announce he was incapacitated due to his crippling polio and needed to resign. If the president refused, Butler would march on the White House with 500,000 war veterans and force him out of power. Butler claimed he refused the offer despite being offered $3 million and the backing of J.P. Morgan’s bank and other important financial institutions.

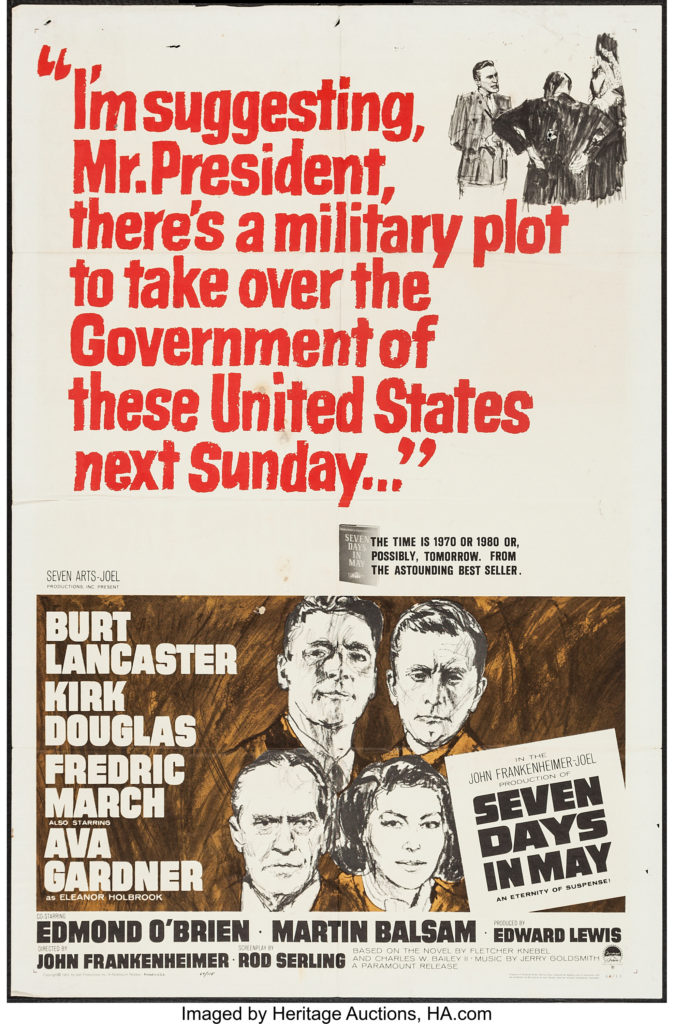

A special committee of the House of Representatives (a forerunner to the Committee on Un-American Activities) headed by John McCormack of Massachusetts heard all the testimony in secret, but no additional investigations or prosecutions were launched. The New York Times thought it was all a hoax, despite supporting evidence. Later, President Kennedy privately mused that he thought a coup d’état might succeed if a future president thwarted the generals too many times, as he had done during the Bay of Pigs crisis. He cited a military plot like the one in the 1962 book Seven Days in May, which was turned into a 1964 movie starring Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas.

In reality, the peaceful transfer of power from one president to the next is one of the most resilient features of the American Constitution and we owe a deep debt of gratitude to the framers and the leaders who have served us so well.

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].