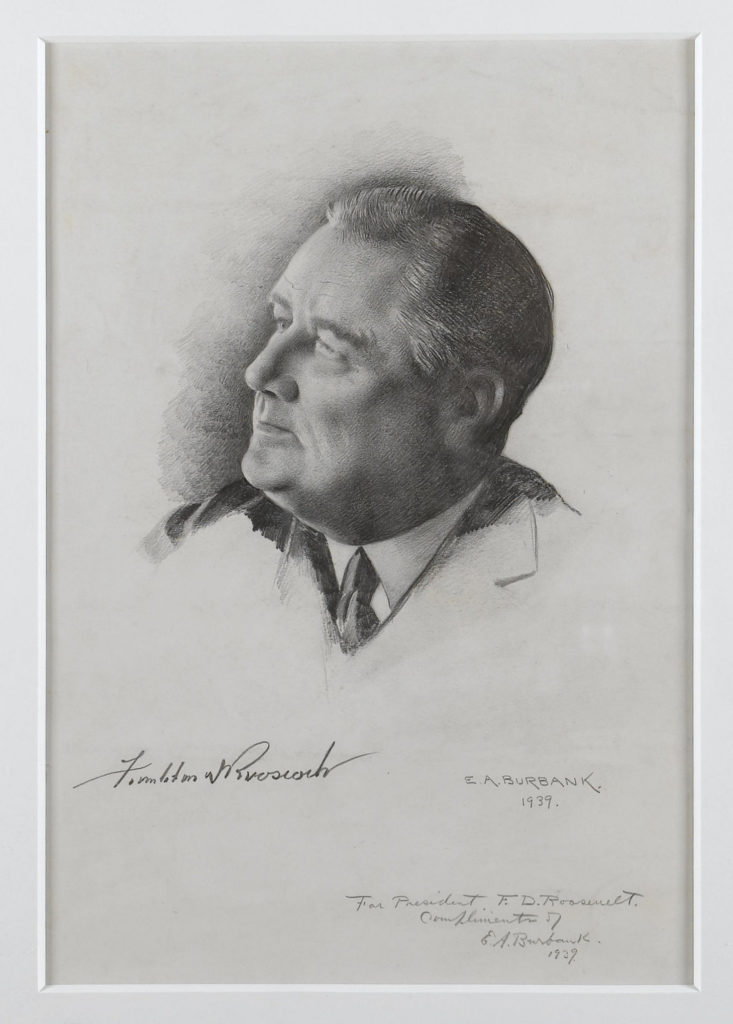

“I hardly know Truman.” – Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1944)

By Jim O’Neal

President Franklin Roosevelt was a tired and worn out man. The worry aroused by his appearance was more than justified. Unbeknown to all but a few, he was suffering from a progressive, debilitating cardiovascular disease. Several elite cardiologists agreed he would be dead within a year, especially if he decided to run for a fourth term. But FDR was determined, and told a few close confidants that he would resign as soon as WWII was concluded satisfactorily.

He had ventured into national politics when his name, youth and political strength in populous New York led to his nomination for vice president in 1920. The DNC had met in June in San Francisco and picked James Cox for the president slot. However, the Republican ticket of Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge won easily.

The following year, the 39-year-old Roosevelt contracted poliomyelitis while vacationing at the family’s summer home on Campobello Island in Canada. He was crippled in both legs, permanently. In a show of intestinal fortitude, he mastered the use of leg braces, crutches and a wheelchair; he built his upper-body strength by swimming. He demonstrated his new skills in dramatic fashion in June 1924 at the National Democratic Convention.

He rose from a wheelchair and, unassisted, walked to the speaker’s rostrum and nominated Al Smith for president. The crowd went wild after Roosevelt crowned Smith “the Happy Warrior of the political battlefield.” Smith ultimately lost the nomination that year; four years later in 1928 he won the nomination but lost the election to Herbert Hoover. The economic good times favored the better-known Hoover, but there was also the lingering issue of Smith’s Catholicism. This would remain an issue until 1960 when Jack Kennedy would vanquish it permanently.

In 1930, FDR was re-elected governor of New York. In the wake of the stock market crash, he convinced the legislature to provide $20 million to the unemployed. This was the first direct unemployment aid by any state and was a harbinger of bigger government programs. It was also a springboard to the 1932 Democratic nomination for president. FDR was so energized that he flew to Chicago to accept – the first time a nominee accepted in person.

No one was surprised at the results of the 1932 election, when FDR defeated Hoover in a landslide. The country had turned on Hoover and the Republicans and was eager and impatient to have the new president installed. This led directly to the 20th Amendment of the Constitution, which advanced the presidential inauguration to Jan. 20 and Congress to Jan. 3. Alas, it didn’t go into effect until 1933. Hoover was full of ideas on how to help the new president, but Roosevelt was less willing to accept any advice, since he had his own plans.

And so it began. With a soothing voice and supreme self-confidence, Roosevelt rallied a fear-ridden country to overcome the Great Depression. With a New Deal, he provided social justice; security to the aged; relief to the unemployed; and higher wages to the working man. He revamped the federal government, adding scores of new agencies and reshaping the Democratic Party from states’ rights into a Hamiltonian model of a strong central government.

Twelve years went by fast, and the last days of the Second World War required a series of critical decisions and it started with a decision on a fourth term. His trusted advisers saw defeat unless something was done about VP Henry Wallace. A plant geneticist by profession, he had become very popular as an author, lecturer and social thinker. To the “wise men,” he seemed pathetically out of place and painfully lacking in political talent. But there was more concern over the president’s declining health, which could no longer be ignored. All realized that the man nominated to run with Roosevelt would probably be the next president.

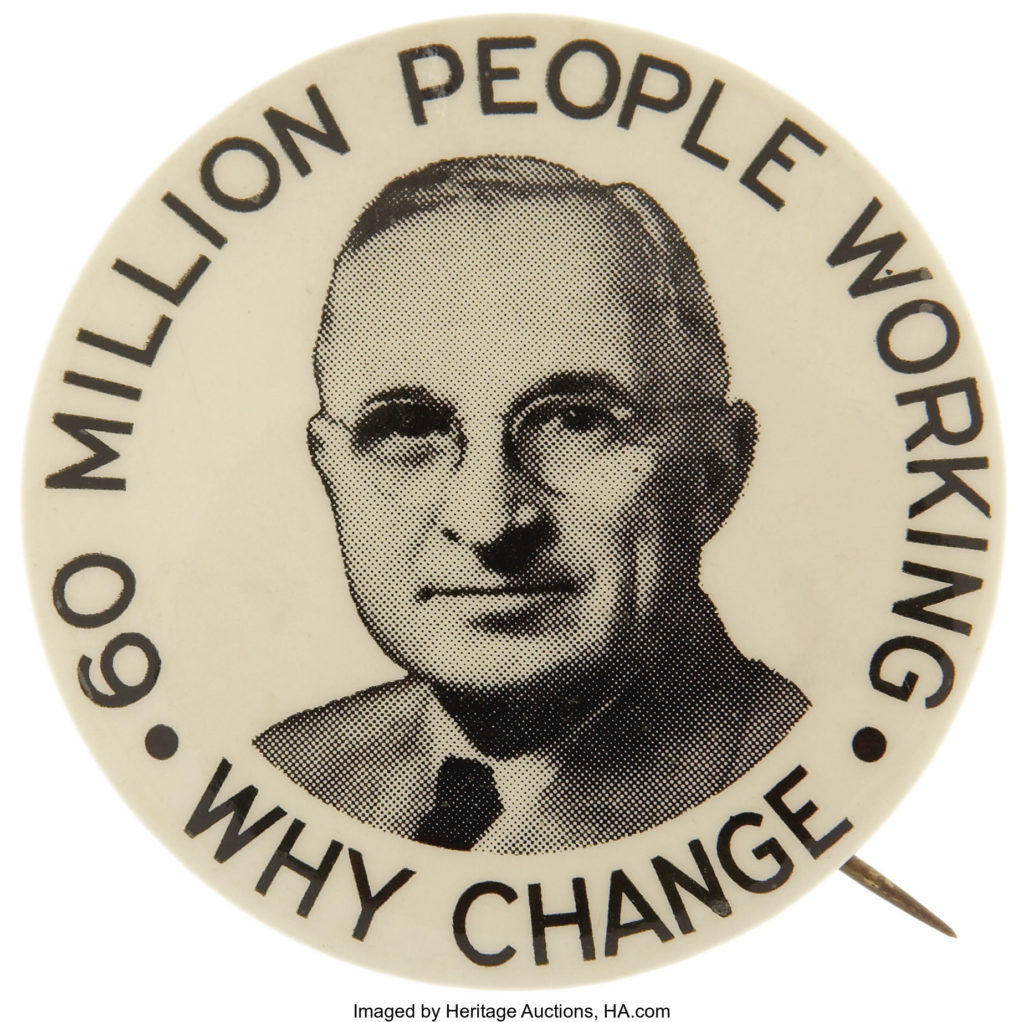

That man turned out to be Senator Harry Truman from Missouri. Together, they would win the 1944 election; 82 days after taking office, Truman would become president when FDR died on April 12, 1945. He would end the war as expected, win re-election in 1948 and become embroiled in another war, this time with Korea. However, with each passing year, Truman continues to gain in stature and now often polls among the top 10 best presidents.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].