By Jim O’Neal

When Barack Obama was sworn in on Jan. 20, 2009, he became the eighth president to have graduated from Harvard, which has educated more U.S. presidents than any other university. Yale is second with five, with George W. Bush counting for both Yale and Harvard (where he earned an MBA).

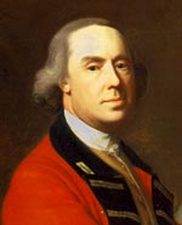

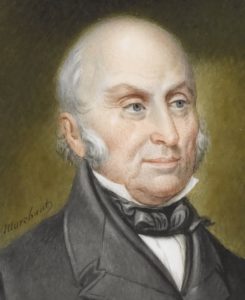

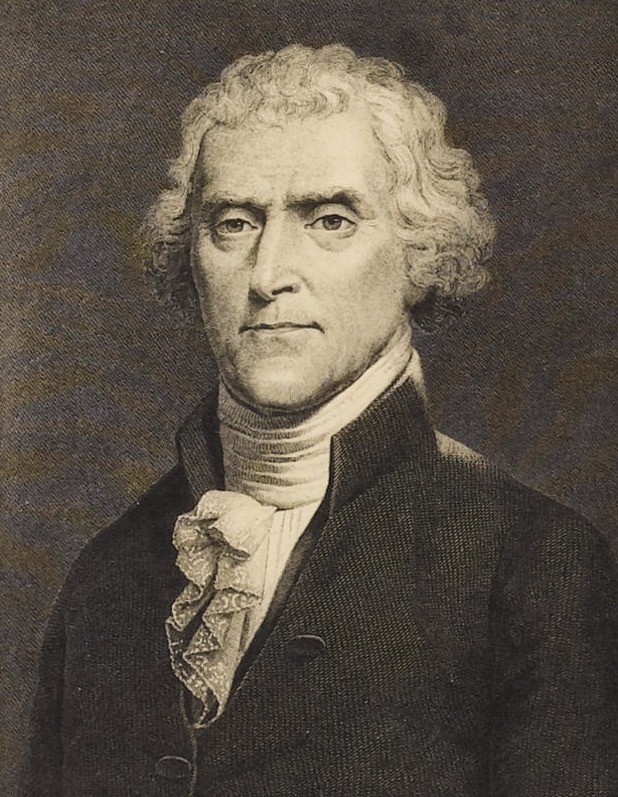

The first of the “Harvard Presidents” goes all the way back to 1796, when John Adams narrowly defeated Thomas Jefferson 71 to 68 in the electoral vote count. It was the only election in history in which a president and a vice president were elected from opposing parties.

However, Jefferson bounced back four years later in a bitter campaign characterized by malicious personal attacks. Alexander Hamilton played a pivotal role in sabotaging President Adams’ attempt to win a second term by publishing a pamphlet that charged Adams was “emotionally unstable, given to impulsive decisions, unable to co-exist with his closest advisers, and was generally unfit to be president.”

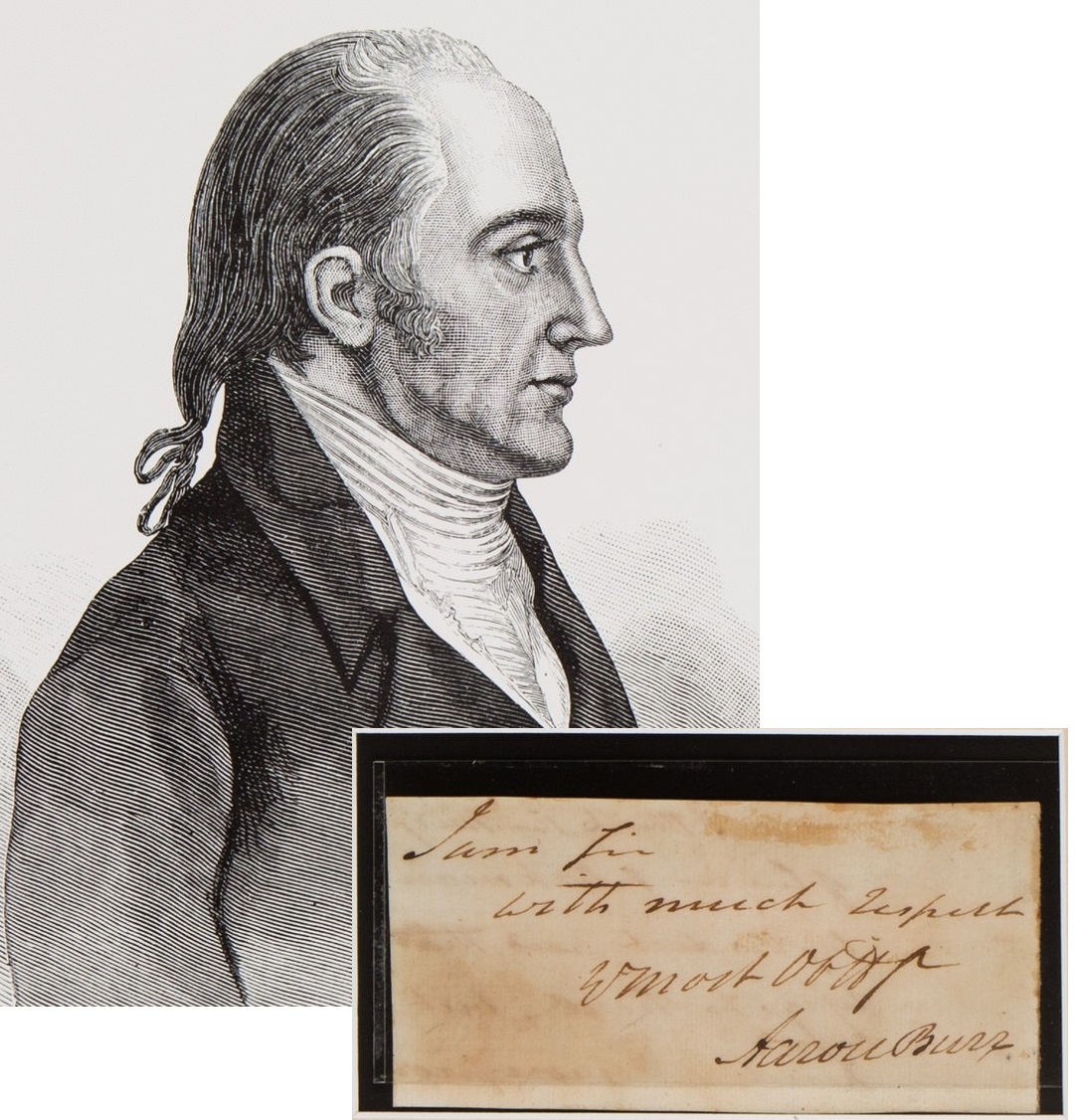

When all the votes were counted in 1800, Adams actually ended up third behind both Jefferson and Aaron Burr (who eventually became vice president). John and Abigail Adams took the loss very emotionally and it alienated their relationship with Jefferson for 20-plus years. Adams departed the White House before dawn on Inauguration Day, skipped the entire inauguration ceremony and headed home to Massachusetts. The two men ultimately reconciled near the end of their lives (both died on July 4, 1826).

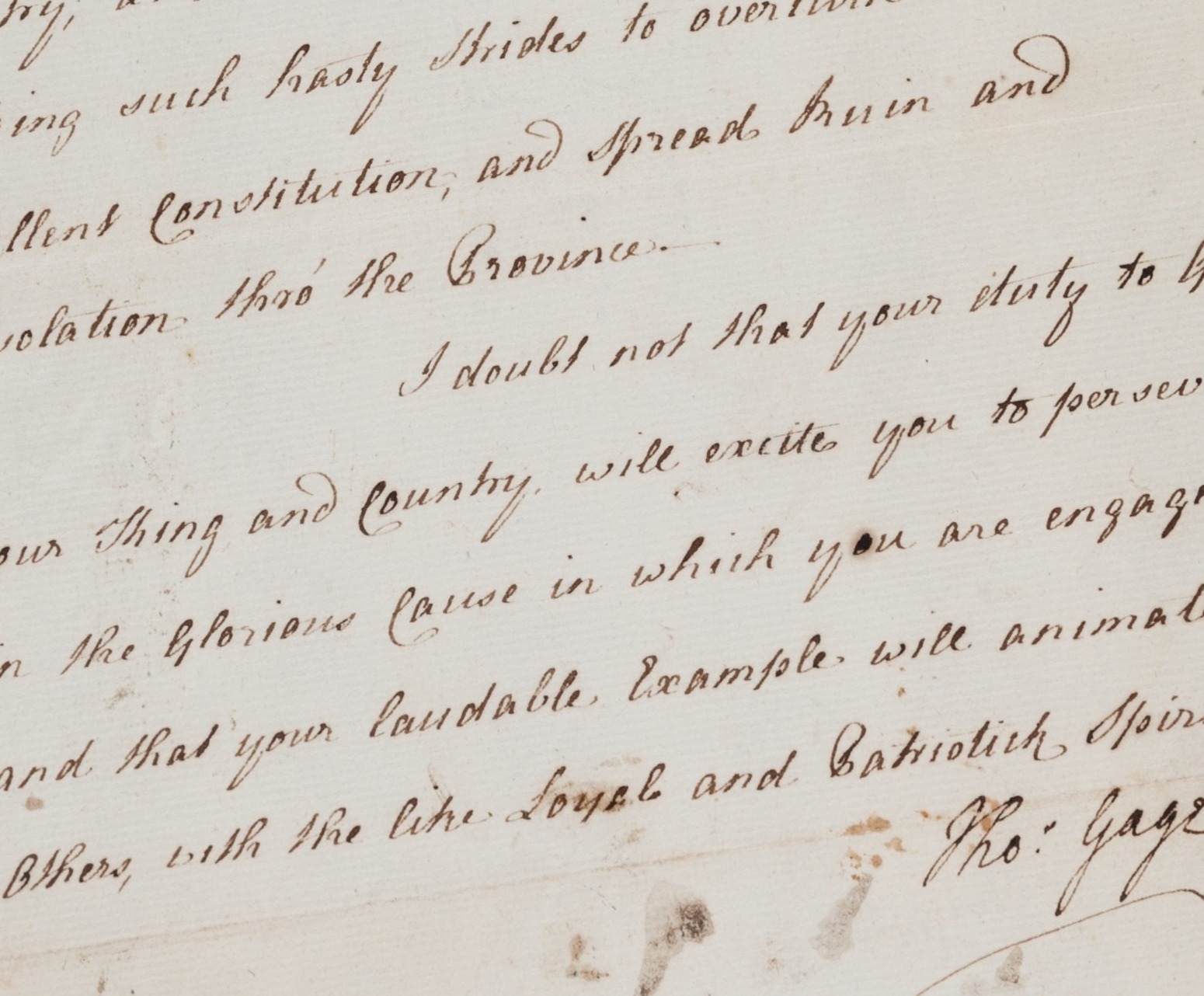

Adams had been an experienced executive-office politician after serving eight years as vice president for George Washington. However, his four years as president were controversial. It started when the Federalist-dominated Congress passed four bills, collectively called the Alien and Sedition Acts, which President Adams signed into law in 1798. The Naturalization Act made it harder for immigrants to become citizens, and the Alien Friends Act allowed the president to imprison and deport non-citizens deemed dangerous or from a hostile nation (Alien Enemy Act). And finally, the Sedition Act made it a crime to make false statements that were critical of the federal government.

Collectively, these bills invested President Adams with sweeping authority to deport resident non-citizens he considered dangerous; they criminalized free speech, forbidding anyone to “write, print, utter or publish … any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writing against the government of the United States … or either House of Congress of the United States … with intent to defame … or bring them into contempt or dispute … or to excite against them or either of them … the hatred of the good people of the United States.”

Editors were arrested and tried for publishing pieces the Adams administration deemed seditious. Editors were not the only targets. Matthew Lyon, a Vermont Congressman, was charged with sedition for a letter he wrote to the Vermont Journal denouncing Adams’ power grab. After he was indicted, tried and convicted, Lyon was sentenced to four months in prison and fined $1,000.

For Vice President Jefferson, the Alien and Sedition Acts were a cause of despair and wonderment. “What person, who remembers the times we have seen, could believe that within such a short time, not only the spirit of liberty, but the common principles of passive obedience would be trampled on and violated.” He suspected that Adams was conspiring to establish monarchy again.

It would not be the last time Americans would sacrifice civil liberties for the sake of national security. More on this later.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].