By Jim O’Neal

I suppose that most people interested in history have given consideration to the traditional question, “Who would you like to have dinner with?” There are many excellent choices, but my personal No. 1 is Benjamin Franklin and his youngest sister, Jane Franklin Mecom. I’d select “Benny and Jenny” (as they were called) since they were so close and corresponded with each other over a string of 60 years.

Jane did not attend any school and Franklin ended up teaching her how to read. She survived him by four years, until 1794, and subsisted almost exclusively on an allowance from Benjamin that included a house until she died. The house was then converted into a monument to Paul Revere. Of her 12 children, she survived all but one. At the time, 25 percent of all children died before their 10th birthday. It was so routine that, from a religious standpoint, children were taught not to fear death.

I would invite Jane to my dinner simply to get a female’s perspective on life in the 18th century. Much of what we know about those times is slanted to a narrow slice of the population (i.e. white males who were landowners). Benjamin was never really committed to religion. Asked about his views when he was near the end, he ducked it by saying he’d never really studied it and would soon be able to find out with a degree of certainty.

The choice of Benjamin might seemingly appear to be obvious: He was a polymath of the first order (a 20th century term reserved for exceptional people). Some rank him on a level with Leonardo da Vinci, despite the stark difference in versatility in creative arts. Even Walter Issacson, who wrote biographies of both men, describes Franklin as “the most accomplished American of his age and influential in inventing the type of society America would become.”

Consider his resume as inventor, diplomat, printer, politics, scientist, the postal system and wit as a writer. It would have to be a l-o-n-g dinner to touch on even a partial list of accomplishments. Besides, there are dozens of modern books on every single topic available on an e-reader in a matter of seconds. Why waste time listening to his dated thinking, which has been overtaken by later experts?

Benjamin Franklin was born in Boston in 1706, which means it was during the reign of Anne, Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland (1702-07). On May 7, 1707, under the Acts of Union, the kingdoms of England and Scotland united as a single sovereign state known as Great Britain. She continued to reign as Queen of Great Britain and Ireland until her death in 1714. Anne was in ill health for much of her life and despite 17 pregnancies, died without any surviving. Under the Act of Settlement (1701), which excluded all Catholics, she was succeeded by a second cousin, George I of the House of Hanover (a German Royal House).

George III became King of Great Britain and Ireland in 1760 at age 22 following the sudden death of his grandfather George II. In his accession speech to Parliament, he played down his Hanoverian connection. “Born and educated in this country,” he said, “I glory in the name of Britain!” In his long life (81 years), George never traveled beyond England … not to Ireland, to the continent, not even to Scotland and most certainly never to America. As an aside, none of his ministers had been to the New World. They had no idea that America had a population of 2.5 million that was doubling every 25 years, a growth rate never seen in recorded history. George III would reign for 59 years, longer than any of his predecessors and only exceeded by two queens: Victoria and Elizabeth II.

He was aware of the outcome of the French and Indian War (the Seven Years’ War that lasted nine years, 1754-1763) that was resolved by the Treaty of Paris. The spoils were perhaps the greatest ever won by force. Britain took Canada from France and half a billion acres of fertile land from the Mississippi River and the Appalachian Mountains. Florida and the Gulf Coast were ceded by Spain. Britain emerged with the most powerful navy in history and with 8,000 sails, the world’s largest merchant fleet. George Macartney penned the still well-known descriptor of “this vast empire on which the sun never sets.”

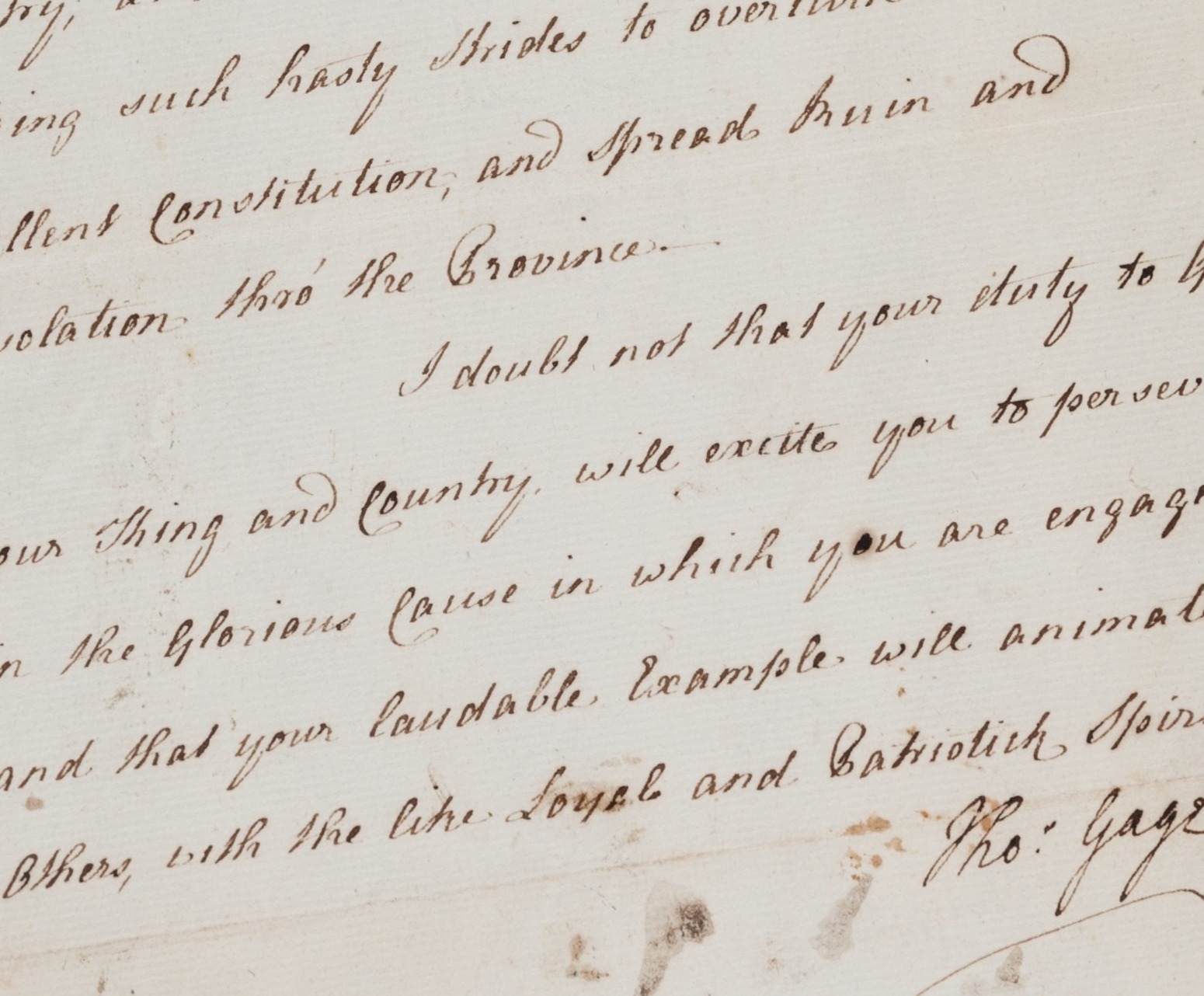

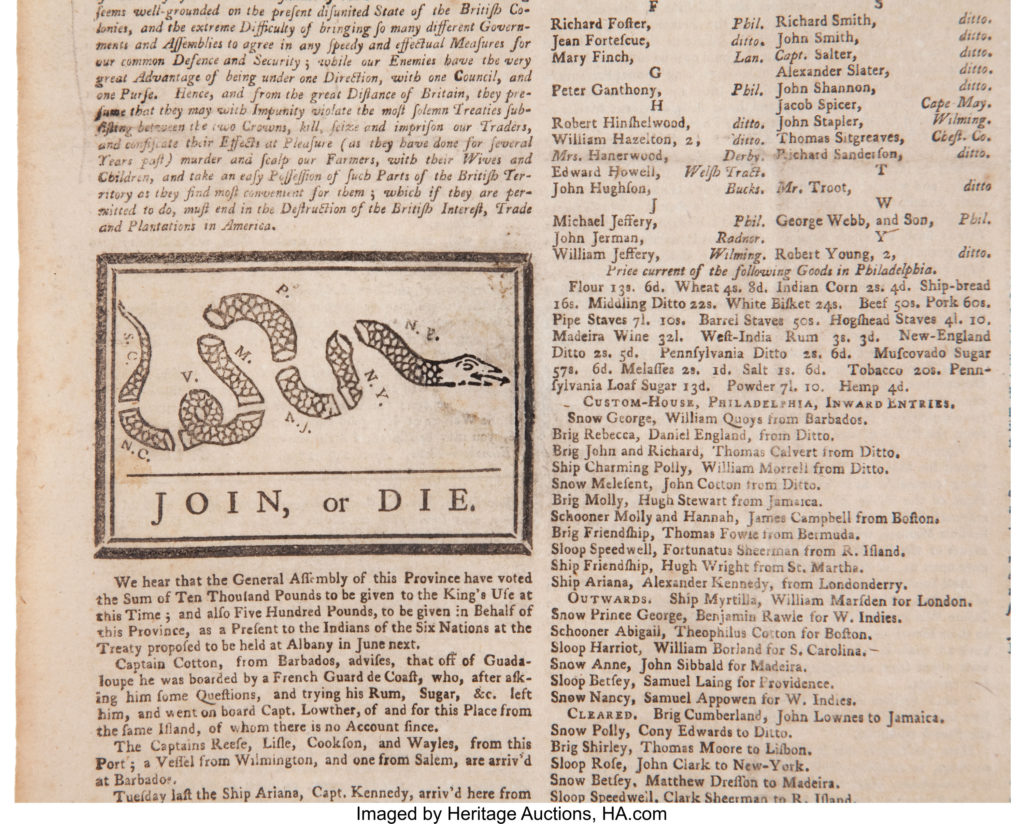

Ten years later in June 1773, King George III participated in a great celebration of his reign over the greatest empire since ancient Rome. However, at the end of the next decade, Britain’s bright future had dimmed by a series of provocative taxes levied on his increasingly rebellious American Colonies: 1764’s Sugar Tax, 1765’s Stamp Act and, finally, the Tea Tax that provoked the Boston Tea Party and lead directly to April 18, 1775, and the Battle of Lexington and Concord and the American Revolution.

The war would last eight years and though at least 1 in 10 Americans would die for the cause, the treasure was beyond measure: freedom from oppression and the creation of a new republic. This is my conversation for Benjamin Franklin. What happened on Jan. 29, 1774, that transformed him from a conciliator to a revolutionary … from a loyalist to the British Crown to “the First American?” … and exactly what role did the Hutchinson Letters Affair play?

The God question can wait, but I would like to know if Benjamin has a sense of humor … and what makes him laugh.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].