By Jim O’Neal

There must have been thousands of American veterans of World War I still alive when I was born in 1937. After all, it had been less than 19 years since the Peace Armistice had been signed in November 1918. Although the war started in Europe in 1914, the United States didn’t get directly involved until April 1917 after a series of events provoked President Wilson to ask Congress to declare war.

However, my only recollections are about the Second World War, when my father and five of my mother’s brothers went to strange-sounding places like Iwo Jima, Guadalcanal, Tarawa and Okinawa. My Saturdays at the movies were (seemingly) exclusively Westerns and war films. Of course, there were the newsreels narrated mostly by Lowell Thomas, the voice of Movietone News. This was the generation that suffered through the Great Depression and earned the title of “the Greatest Generation” (Tom Brokaw) for their courage, sacrifice and honor. I give them a lot of credit for a time in the 1950s that I fondly recall with television, my own car, more money than I could spend and unlimited basketball, baseball and surfing.

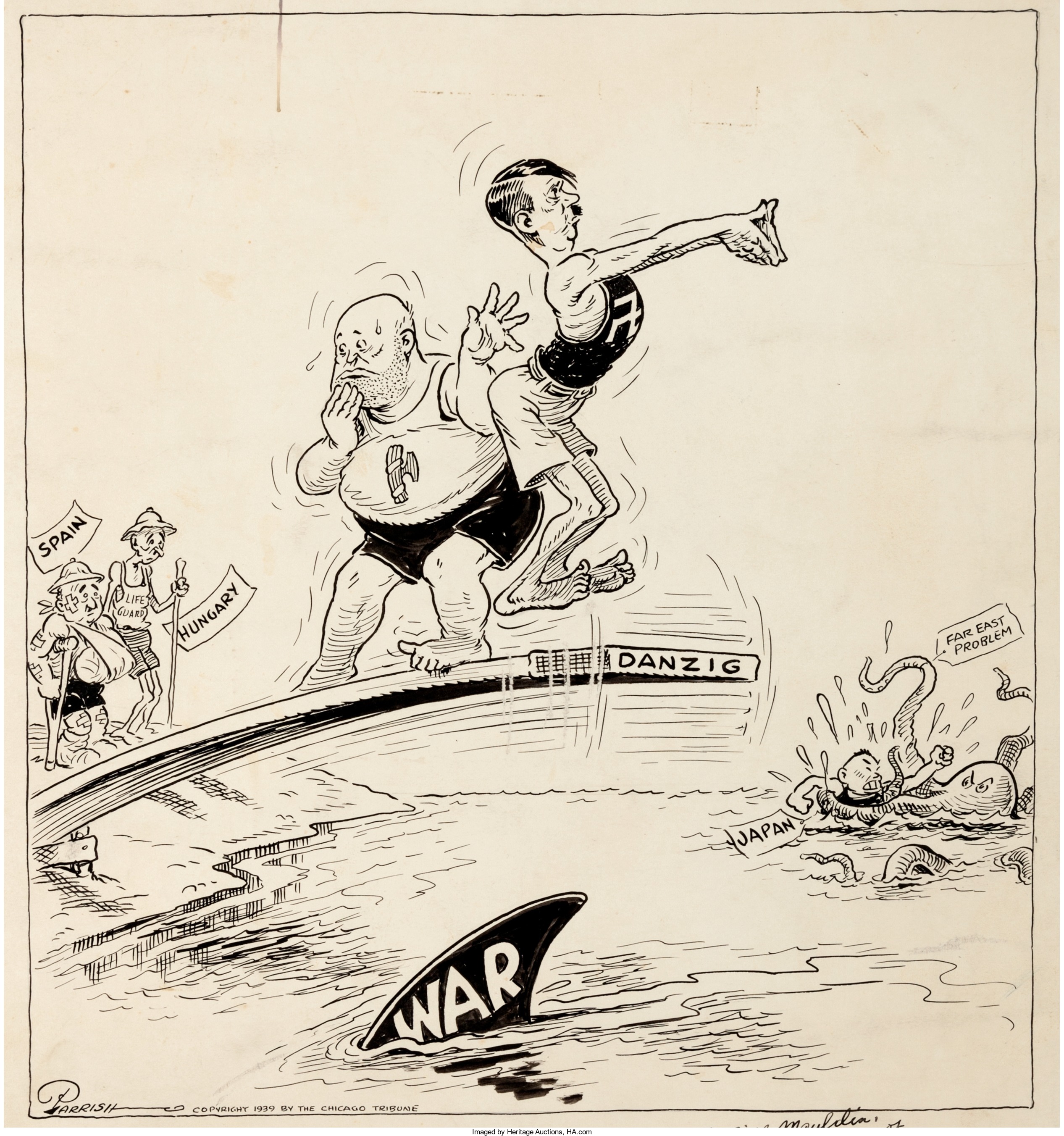

Still, historians agree that the First World War had a major impact in shaping the modern world. A war of unprecedented violence, it upended the Victorian Era’s peace and prosperity. It unleashed mechanized warfare and death on a level that was staggering. Concurrently, it fundamentally altered the social norms for economics, psychology and liberalism that dated back to the Enlightenment. No one has developed an acceptable theory on the confluence of events that shattered the relationships of monarchies with blood and familial ties. The complicating treaties and alliances served as an obvious domino factor, but a single circuit breaker had the power to defuse the entire situation if it had been employed early.

Yet not a single leader had the courage or foresight to simply call “Time out!” and stop the equivalent of a runaway train. This strategic void led directly to the loss of 10 million lives and the destruction of a continent that had slowly evolved a benevolent culture with so much potential. Fortunately, the war was primarily rural and most of the grand historic buildings were spared; fate would not be so kind to the next confrontation … with thousands of bombers, guided bombs and the destruction of entire cities.

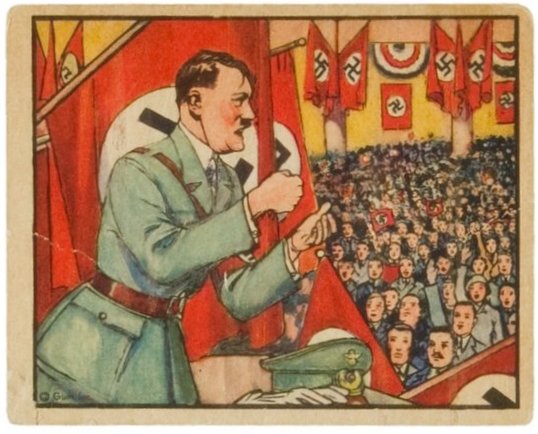

Perhaps worse, though, was the post-war legacy of hatred that made the horrific second tragedy inevitable. Consider the mindset of Adolf Hitler on Sept. 18, 1922, when he warned, “It cannot be that 2 million Germans should have fallen in vain … No, we do not pardon, we demand … vengeance!” Are these the words of a sane man who would be satisfied to regroup, rebuild and start over? Or a clever psychopath who would corrupt the minds of people, even as they were struggling with the punishment required by the Treaty of Versailles and the English, French and Russians exacting their revenge? Thousands of books have answered this with clarity.

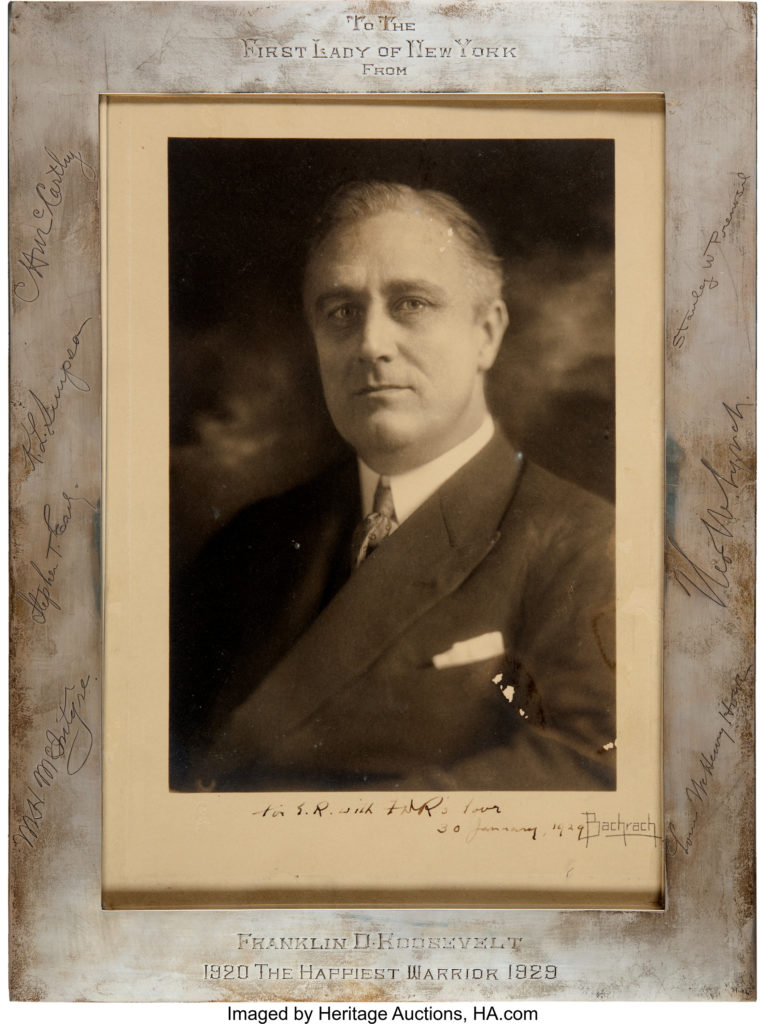

Sadly, Americans and especially President Wilson would be seduced by a vague concept of a “14 Point Peace Plan” and a “League of Nations” to prevent future war, yet couldn’t even pass an obstinate Congress. It was another academic chimera, followed by a disabling stroke. Wilson’s successor was a flawed man, surrounded by corrupt men and public scandal. President Harding’s death in 1920 was unexpected but provided the opportunity for his vice president to perform an overdue house cleaning.

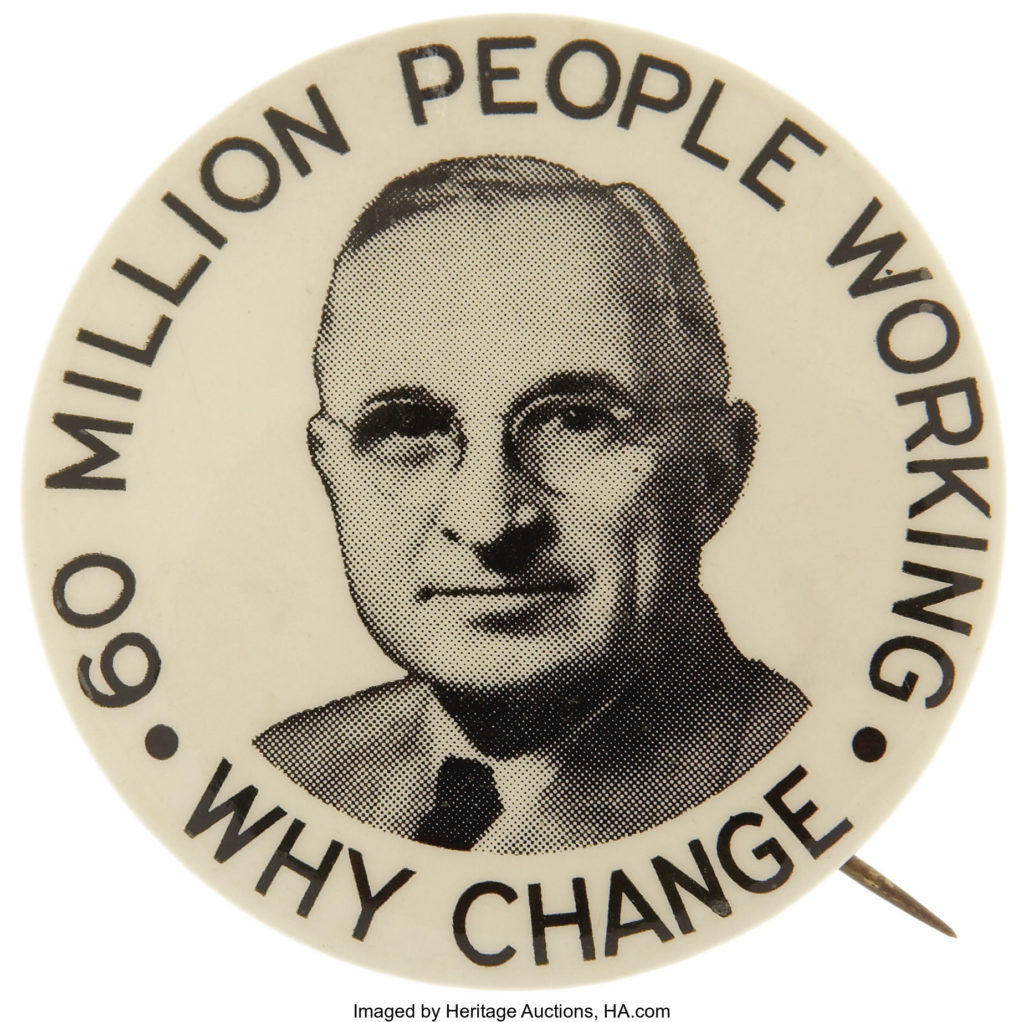

Calvin Coolidge was just the man to address the scandal-ridden administration of Warren G. Harding. His list of accomplishments are still not well known, but included cutting taxes four times, a budget surplus every year in office, and reduction of the national debt by a third. In many respects, he was a man of a bygone era. He wrote his own speeches, had only one secretary and didn’t even have a telephone on his presidential desk. Little wonder that President Reagan, who admired Coolidge’s efforts toward a smaller government and lower taxes, placed Silent Cal’s portrait in the White House Cabinet Room next to Lincoln and Jefferson.

Today, it’s not clear precisely how many wars we are in and how many have the exit strategy that Colin Powell considers essential to any military action (along with a clear objective and overwhelming forces to ensure victory). I wish I’d heard more from those WWI veterans that prompted this lesson!

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].