By Jim O’Neal

From 1939 to the winter of 1941, the German military won a series of battles rarely equaled in the history of warfare. In rapid succession, Poland, Norway, France, Belgium, Holland, Yugoslavia, Denmark and Greece all fell victim to the armed forces of the Third Reich. In the summer and fall of 1941, the USSR came close to total defeat at the hands of the Wehrmacht, losing millions of soldiers on the battlefield and witnessing the occupation of a large portion of Russia and the Ukraine. The German air force, the Luftwaffe, played a central role in this remarkable string of victories.

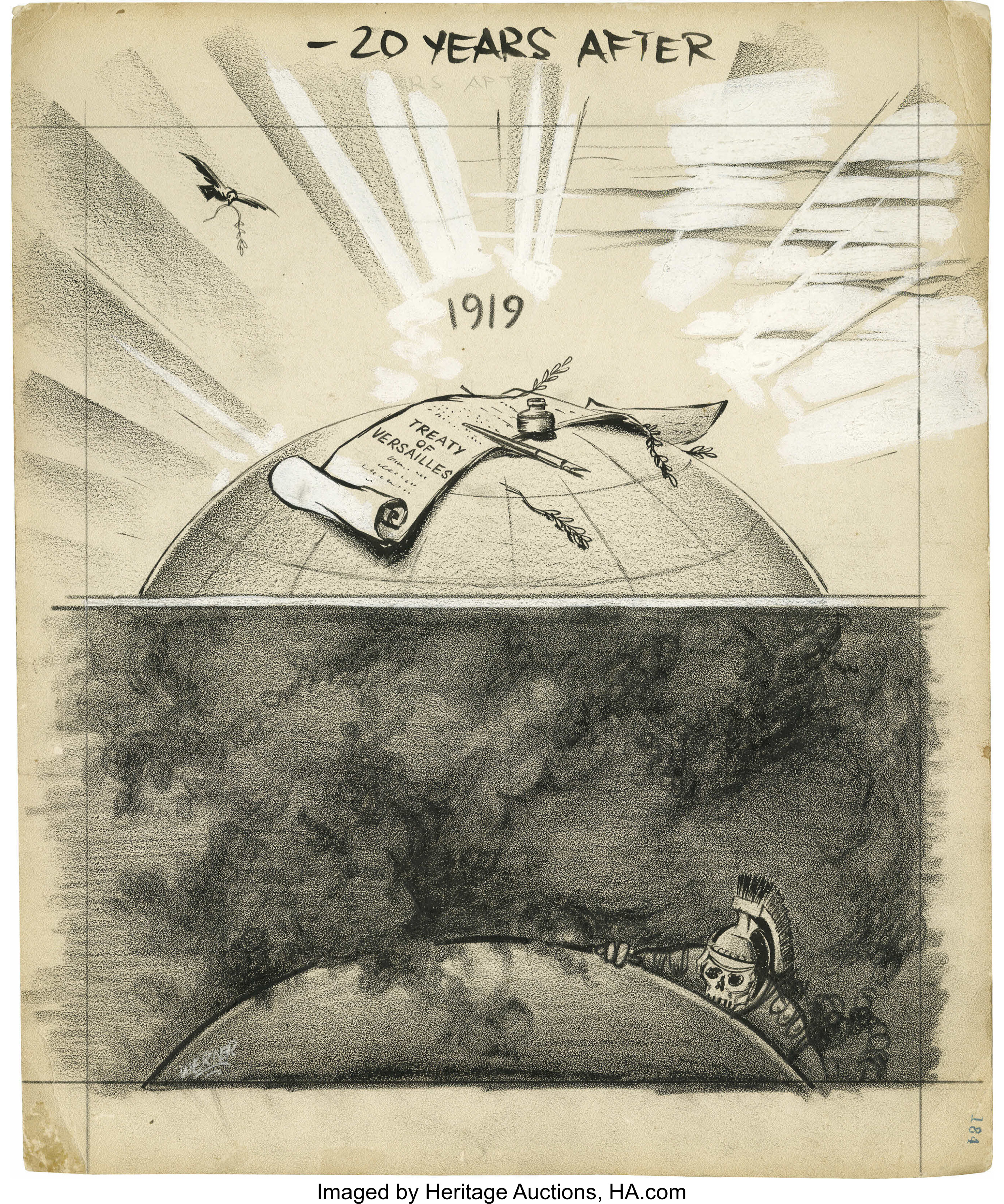

It was even more startling to those countries that had participated in WWI and taken draconian anti-war measures when it ended. This was simply something that was NEVER supposed to happen again, much less a mere 20 years later. How was it even possible?

The Allied powers had been so impressed with the combat efficiency of the German Luftwaffe in WWI that they made a concerted effort to eliminate Germany’s capability to wage war in the air. Then they crippled their civilian aviation capability just to be certain. The Allies demanded the immediate surrender of 2,000 aircraft and rapid demobilization of the Luftwaffe. Then in May 1919, the Germans were forced to surrender vast quantities of aviation material, including 17,000 more aircraft and engines. Germany was permanently forbidden from maintaining a military or naval air force.

No aircraft or parts were to be imported, and in a final twist of the knife, Germany was not allowed to control their own airspace. Allied aircraft were granted free passage over Germany and unlimited landing rights. On May 8, 1920, the Luftwaffe was officially disbanded.

Other provisions of the Versailles Treaty dealt with the limits of the army and navy, which were denied tanks, artillery, poison gas, submarines and other modern weapons. Germany was to be effectively disarmed and rendered militarily helpless. An Inter-Allied Control Commission was given broad authority to inspect military and industrial installations throughout Germany to ensure compliance with all restrictions.

However, one critical aspect got overlooked in the zeal to impose such a broad set of sanctions. They left unsupervised one of the most influential military thinkers of the 20th century … former commander-in-chief of the German Army Hans von Seeckt. He was the only one who correctly analyzed the operational lessons of the war, and accurately predicted the direction that future wars would take. Allied generals clung to outdated principles like using overwhelming force to overcome defensive positions, while Von Seeckt saw that maneuvers and mobility would be the primary means for the future. Mass armies would become cannon fodder and trench warfare would not be repeated.

The story of the transformation of the Luftwaffe is a fascinating one. Faced with total aerial disarmament in 1919, it was reborn only 20 years later as the most combat-effective air force in the world. Concepts of future air war along with training and equipment totally trumped the opposition, which was looking backward … always fighting the last war.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].